Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden (ACB) Score Calculator

Check Antihistamine Risk

Enter the name of an antihistamine to see its cognitive risk score on the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden scale (0-3)

Antihistamine Risk Assessment

- 0 = No anticholinergic effect

- 1 = Low risk

- 2 = Moderate risk

- 3 = High risk

For years, millions of older adults have reached for over-the-counter sleep aids like Benadryl to help them fall asleep. It’s cheap, easy to find, and works quickly. But what if that nightly pill could be quietly affecting your brain? The truth is more complicated than a simple warning label. While some studies link long-term use of certain antihistamines to higher dementia risk, others find no clear connection. The real issue isn’t all antihistamines-it’s the first-generation ones with strong anticholinergic effects.

What Makes Some Antihistamines Riskier Than Others?

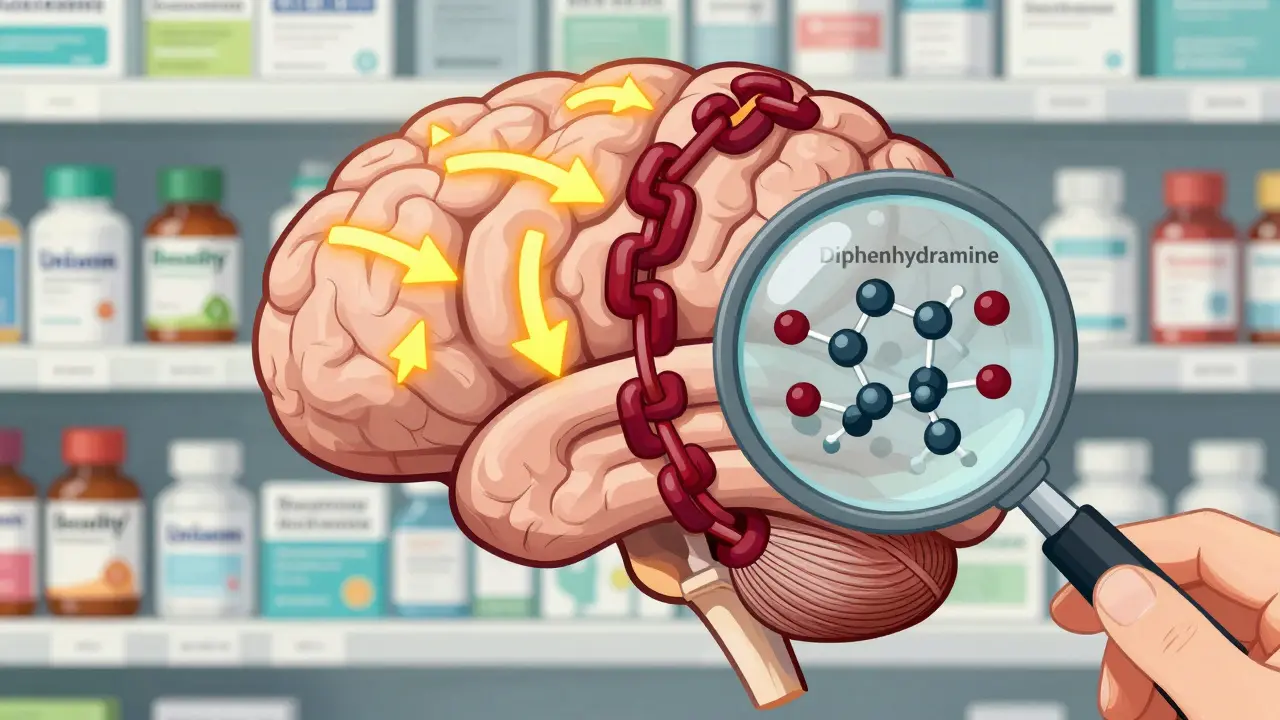

All antihistamines block histamine, the chemical your body releases during allergies. But not all of them act the same way in your brain. First-generation antihistamines-like diphenhydramine (Benadryl), doxylamine (Unisom), and chlorpheniramine (Chlor-Trimeton)-were designed to cross the blood-brain barrier. That’s why they make you drowsy. But this same feature lets them also block acetylcholine, a key neurotransmitter for memory and thinking.

Think of acetylcholine like a messenger in your brain. When it’s blocked, signals that help you remember names, follow conversations, or find your keys start to slow down. This isn’t just temporary drowsiness-it’s a chemical disruption that builds up over years. First-generation antihistamines bind tightly to muscarinic receptors in the brain, with binding strength (Ki values) between 10 and 100 nanomolar. That’s strong enough to interfere with normal brain function.

Second-generation antihistamines-like loratadine (Claritin), cetirizine (Zyrtec), and fexofenadine (Allegra)-were made differently. They’re designed to stay out of the brain. Thanks to special pumps called P-glycoproteins, they’re pushed back into the bloodstream before they can enter the central nervous system. Their anticholinergic activity is 100 to 1,000 times weaker than first-generation versions. That’s why they don’t cause the same level of drowsiness or cognitive fog.

The Evidence: Mixed, But the Warning Stands

A 2015 study in JAMA Internal Medicine looked at over 3,400 people aged 65 and older over 10 years. It found that those who took anticholinergic drugs regularly had a higher chance of developing dementia. But when researchers broke down the data, antihistamines didn’t show the same risk as antidepressants or bladder medications. In fact, the hazard ratio for antihistamines was 1.00-meaning no increased risk.

That same study was repeated in 2022 with a larger group of nearly 9,000 older adults. This time, 3.83% of those taking first-generation antihistamines developed dementia, compared to just 1.0% of those using second-generation ones. But even that gap didn’t reach statistical significance. The adjusted hazard ratio was 1.029-so close to 1.0 that it could easily be due to chance.

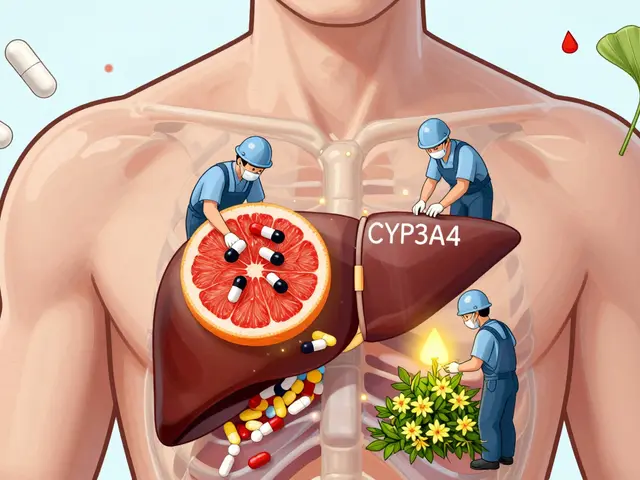

Then there’s the 2021 meta-analysis in Age and Ageing that said anticholinergic drugs overall raised dementia risk by 46%. But here’s the catch: it grouped every anticholinergic together-antidepressants, bladder meds, Parkinson’s drugs, and antihistamines. That’s like saying all cars are dangerous because one model has a faulty brake system. When you look at antihistamines alone, the signal fades.

Still, experts don’t ignore the pattern. The American Geriatrics Society’s 2023 Beers Criteria, which guides doctors on safe prescribing for older adults, gives first-generation antihistamines a clear ‘Avoid’ rating. Why? Because even if the data isn’t perfect, the biological mechanism is solid. Blocking acetylcholine for years in an aging brain is like slowly turning down the volume on your thoughts. And for someone already at risk-maybe with early memory changes, diabetes, or high blood pressure-that extra nudge could matter.

Who’s Still Taking These Pills?

Here’s the uncomfortable part: people keep using them. A 2022 survey by the National Council on Aging found that 42% of adults over 65 regularly used OTC antihistamines for sleep. And 78% had no idea these drugs had anticholinergic effects. On Reddit, a geriatric care manager shared that 83% of her clients over 70 were taking diphenhydramine every night-just because it was ‘what their doctor told them.’

Drug companies know this. Benadryl still holds 62% of the OTC sleep aid market, even as sales have dropped 15% since 2019. The label still says ‘may cause drowsiness’-not ‘may increase dementia risk.’ The FDA hasn’t required stronger warnings for OTC versions, even though prescription anticholinergics now carry dementia warnings. Meanwhile, the European Medicines Agency updated its patient leaflets in 2022 to include a note about ‘potential long-term cognitive effects.’

And then there are the stories. On AgingCare.com, a daughter wrote: ‘My mother’s doctor prescribed Benadryl for years to help her sleep, and now she has dementia-I can’t help but wonder.’ She’s not alone. These aren’t just statistics. They’re real lives.

What Should You Do Instead?

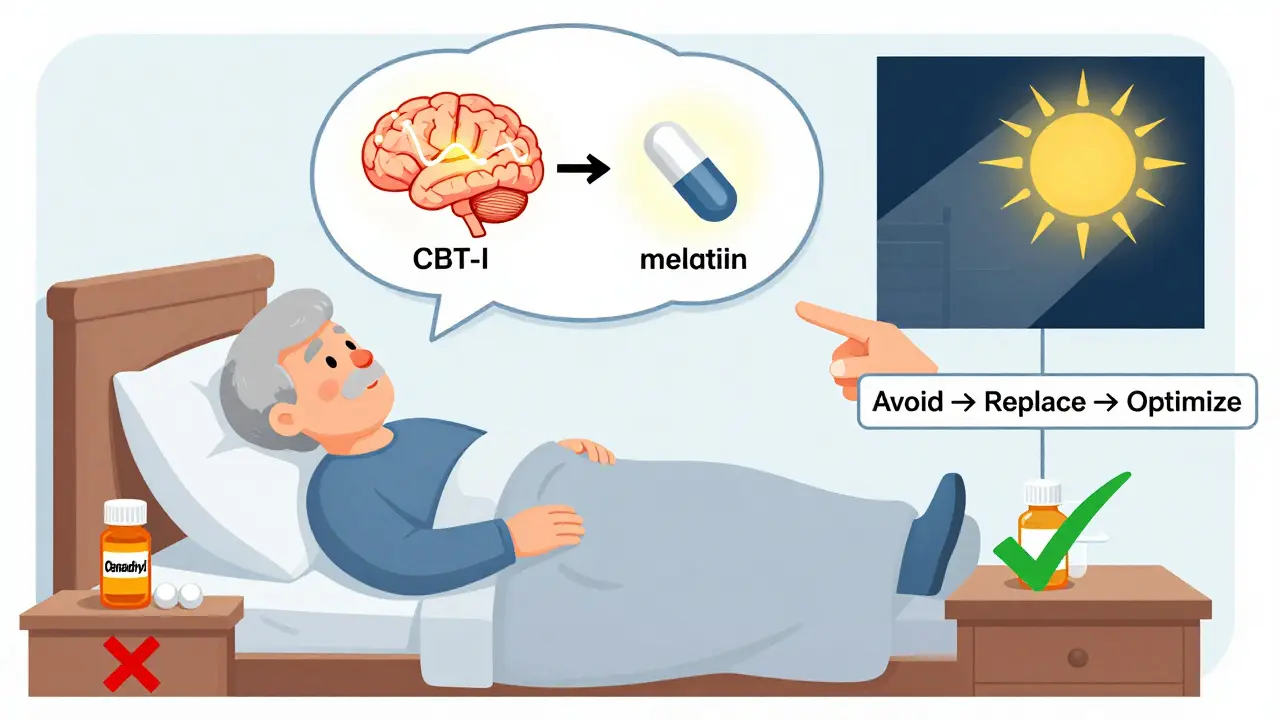

If you or a loved one is using diphenhydramine or doxylamine for sleep, it’s not too late to change. The first step is simple: talk to your doctor. Don’t stop cold turkey-sudden withdrawal can cause rebound insomnia or anxiety. Ask about switching to a second-generation antihistamine. Loratadine or cetirizine won’t make you sleepy, but they’ll still treat allergies. For sleep, they’re not ideal, but they’re far safer than the first-generation options.

There are better alternatives. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) is proven to work. A 2022 meta-analysis in JAMA Psychiatry found it’s 70-80% effective in older adults. It teaches you how to reset your sleep cycle without drugs. The problem? There aren’t enough therapists. Wait times average over eight weeks. And Medicare only pays $85-$120 per session, so many providers don’t take it.

Other options include melatonin (especially for circadian rhythm issues), low-dose doxepin (Silenor)-which has an anticholinergic burden score of just 1-or even simple behavioral changes like avoiding screens before bed, keeping a cool room, or getting morning sunlight.

What’s Next?

The science is still evolving. The ABCO study, launched in 2023 with $4.2 million in NIH funding, is tracking 5,000 older adults for a decade. Early data from the UK Biobank suggests that people who use antihistamines for sleep might already have underlying sleep disorders-like sleep apnea-that are the real drivers of cognitive decline, not the pills themselves.

Meanwhile, the American Geriatrics Society is preparing its 2024 Beers Criteria update. Expect more precise guidance, possibly with risk levels tied to specific drugs and dosages. The FDA is also reviewing all anticholinergic medications, with findings expected in mid-2024.

For now, the safest bet is this: if you’re over 65 and taking a sleep aid with diphenhydramine or doxylamine as the active ingredient, ask your doctor if there’s a safer option. Don’t assume it’s harmless because it’s sold over the counter. Your brain doesn’t know the difference between a prescription and a shelf item-it only knows what chemicals it’s been exposed to.

Quick Summary

- First-generation antihistamines (like Benadryl) have strong anticholinergic effects and should be avoided in older adults.

- Second-generation antihistamines (like Claritin and Zyrtec) have minimal brain effects and are much safer.

- Studies show mixed results, but expert guidelines consistently recommend avoiding first-generation options in seniors.

- Over 40% of older adults use these drugs for sleep-many without knowing the risks.

- Non-drug options like CBT-I are more effective and safer for long-term sleep problems.

Do all antihistamines increase dementia risk?

No. Only first-generation antihistamines-like diphenhydramine and doxylamine-have strong anticholinergic effects linked to cognitive decline. Second-generation antihistamines like loratadine, cetirizine, and fexofenadine have little to no effect on the brain and are considered safe for long-term use in older adults.

Can I still use Benadryl occasionally?

An occasional dose for allergies or a single night of sleep trouble is unlikely to cause harm. The concern is long-term, daily use over years. If you’re taking it every night, it’s time to talk to your doctor about alternatives.

Why do doctors still prescribe diphenhydramine?

Many older patients were prescribed it years ago when the risks weren’t well known. Some doctors still use it because it’s cheap, familiar, and works fast. But guidelines from the American Geriatrics Society and others now strongly advise against it. A medication review every six months can help identify and replace these drugs.

What’s the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden (ACB) scale?

The ACB scale rates how much a drug blocks acetylcholine in the brain. Diphenhydramine is rated a 3-the highest level of burden. Second-generation antihistamines like fexofenadine are rated 0, meaning no significant effect. The scale helps doctors compare risks across different medications.

Are there non-drug ways to improve sleep in older adults?

Yes. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) is the most effective long-term solution, with success rates of 70-80%. Other helpful strategies include maintaining a consistent sleep schedule, avoiding caffeine after noon, getting morning sunlight, and keeping the bedroom cool and dark. These approaches don’t carry any drug risks.

9 Comments

Pat Mun

I’ve been using Zyrtec for years instead of Benadryl, and honestly? I didn’t even know there was a difference until I read this. My mom used to take diphenhydramine every night for ‘sleep’-she thought it was just a sleepy pill, not a brain fogger. I’m glad this got out there. I’ve started gently nudging my 70-year-old uncle toward melatonin and better sleep hygiene. He’s resistant, but hey, one conversation at a time. I’m not here to scare people, just to share what I’ve learned. Your brain doesn’t care if the pill is OTC or prescription-it just knows what it’s been fed for decades. Small changes add up.

Also, CBT-I is legit. I tried it for my own insomnia last year. Took six weeks, no pills, and now I sleep like a baby. No more 3 a.m. panic scrolling. Worth every penny, even if Medicare doesn’t cover it. Talk to your doc. Seriously.

And for the love of all things sane, stop calling it ‘just a sleepy pill.’ That’s like calling a chainsaw ‘just a loud tool.’

Sophia Nelson

This whole article is fearmongering. People have been taking Benadryl for decades and their brains are fine. You’re acting like one pill is going to rot your neurons. My grandma took it every night for 20 years and she still remembers my birthday. Stop scaring seniors into buying expensive ‘sleep therapy’ that no one has time for. Also, who even has time for CBT-I? Eight-week waitlist? That’s ridiculous. Just let people sleep. This is why medicine is so broken-overcomplicating simple things.

steve sunio

lol this is why i hate american medica system. they make everything a crisis. benadryl? oh no it cause dementia? what about the 500mg of tylenol i take every day? or the 3 cokes? or the 12 hours of screen time? nope. only antihistamines? this is fake science. i saw a study in nigeria where people take dipyridamole for 40 years and no dementia. so maybe its not the drug, its the fact you live in a culture that thinks a pill solves everything. also, i think the real problem is people dont have jobs and sit around all day. thats why they cant sleep. not because of benadryl. fix the system not the drug.

Ernie Simsek

YUP. I’ve been telling my aunt for years not to take Benadryl. She’s 74, takes it every night like clockwork. Last time I visited, she could barely remember my dog’s name. 😬 I showed her the ACB scale-she thought it was a new phone app. Then I showed her the Claritin box on the shelf next to it. She went ‘Wait… this one doesn’t make me groggy?’ 🤯

She switched last week. No more 3 a.m. zombie walks to the fridge. And guess what? She sleeps just as well. No drama. No rebound insomnia. Just… better brain. Also, melatonin 3mg? Works like a charm. 🙌

PS: Why does the FDA still let these labels say ‘may cause drowsiness’ and not ‘may slowly erase your memories’? 🤦♂️

Reggie McIntyre

It’s wild how we treat our brains like they’re just machines you can plug and play with. You wouldn’t dump motor oil into your car’s coolant tank and expect it to run fine. But we do this with our neurochemistry every day. First-gen antihistamines? They’re not just sleepy pills-they’re brain dampeners. And we’ve normalized it. ‘Oh, it’s just Benadryl.’ Like it’s a candy. It’s not. It’s a pharmacological sledgehammer to your cholinergic system.

I’ve been researching this since my dad’s diagnosis. He was on diphenhydramine for 12 years. We never connected the dots until it was too late. Now I’m an advocate. Not because I’m scared-I’m pissed. Pissed that we market these as ‘safe’ because they’re OTC. Pissed that doctors still write scripts for them. Pissed that we don’t have better access to CBT-I. This isn’t about fear. It’s about dignity. Your brain deserves better than a 1950s sleep aid.

Gloria Ricky

I work in home care and I see this ALL the time. Elderly clients on Benadryl for sleep, allergies, even anxiety. One lady told me she takes two because ‘one doesn’t knock me out anymore.’ 😔

I showed her the Zyrtec box. She said, ‘But this one doesn’t help me sleep.’ I said, ‘No, but it doesn’t mess with your thinking either.’ She looked at me like I spoke Martian. Took me three weeks of gentle nudging, but she switched. Now she’s sharper. More alert. Less confused in the mornings. And no more falls. 🙏

Also, melatonin + blackout curtains + no caffeine after 2pm? Game changer. No magic pill. Just simple stuff. Why isn’t this taught in senior centers? We need more outreach. Not more pills.

Stacie Willhite

I just want to say thank you for writing this. My mom was on diphenhydramine for 15 years. I didn’t know until last year that it could be linked to her memory loss. We switched her to loratadine for allergies and melatonin at night. She’s not ‘cured’-but she’s more present. She remembers my kids’ names again. She laughs more. It’s not a miracle. But it’s something.

I wish this info had been easier to find. I spent months digging through studies. No one told me. Not her doctor. Not the pharmacist. Not the ‘senior health’ website she trusted. This article? It’s a lifeline.

Jason Pascoe

Interesting stuff. I’m from Australia and we’ve had the ‘anticholinergic burden’ flag on OTC meds for years. Our TGA actually requires a warning on labels now. It’s not perfect, but it’s something. I’ve seen older folks here switch to second-gen antihistamines without issue. The real kicker? The cost. Benadryl is cheaper. But if you factor in falls, ER visits, and cognitive decline? It’s not. We need better public education-not just medical guidelines. Maybe put it on the side of the box like ‘May cause drowsiness’-but ‘May impair memory over time.’ Simple. Clear. Can’t ignore it.

Sonja Stoces

Oh please. Another fear-driven article. The ‘dementia risk’ is based on correlation, not causation. People who take Benadryl for sleep are ALREADY at higher risk-they have sleep apnea, depression, diabetes. It’s not the drug. It’s the underlying conditions. You’re blaming the pill because it’s easy. Meanwhile, the real culprits-sedentary lifestyles, poor diets, chronic inflammation-are ignored. Also, second-gen antihistamines? They’re not ‘safe.’ They’re just less sedating. Your brain still reacts. This is junk science dressed up as wisdom.