Every year, hundreds of thousands of people in the UK and across the world are hospitalized because of unexpected side effects from medications they took exactly as prescribed. These aren’t rare accidents - they’re adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and for many, they’re preventable. The truth is, your genes play a bigger role in how your body handles medicine than you might think. Two people can take the same drug at the same dose, and one stays fine while the other ends up in the ER. Why? It often comes down to differences in how their bodies break down drugs - and those differences are written into their DNA.

How Your Genes Control How Drugs Work in Your Body

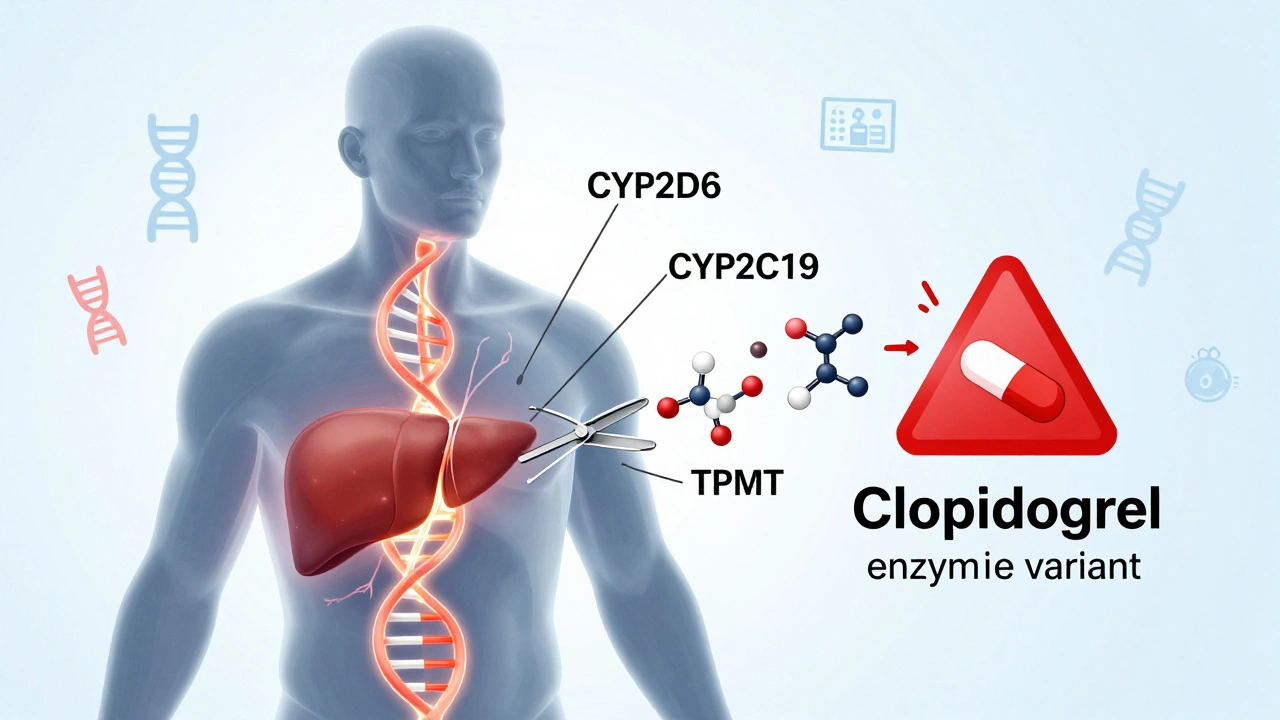

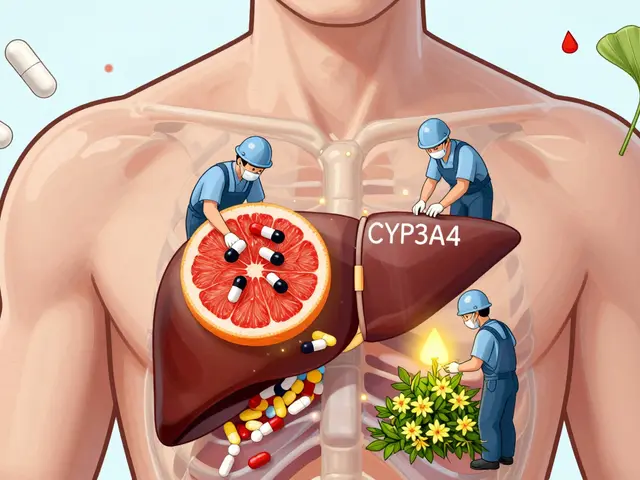

Your body uses enzymes - mostly made by genes like CYP2D6, CYP2C19, and TPMT - to process medications. These enzymes act like molecular scissors, cutting drugs into forms your body can use or get rid of. But not everyone has the same scissors. Some people have genes that make their scissors too slow. Others have scissors that cut too fast. And some don’t have the right scissors at all.

Take clopidogrel, a common blood thinner after a heart attack. About 30% of people carry a variant in the CYP2C19 gene that makes this drug useless. Their bodies can’t turn it into its active form. Without testing, they’re left with no protection against clots - and no idea why. That’s not a failure of the drug. It’s a failure of one-size-fits-all prescribing.

Or consider carbamazepine, used for epilepsy and nerve pain. In people of Asian descent, a single gene variant - HLA-B*1502 - increases the risk of a deadly skin reaction called Stevens-Johnson syndrome by more than 100 times. Testing for this variant before prescribing cuts that risk by 95%. It’s not guesswork. It’s science.

The PREPARE Study: Proof That Testing Works

In 2023, the largest real-world trial ever done on this topic - the PREPARE study - published its results in The Lancet. Over 7,000 patients across seven European countries were tested for 12 key genes before starting common medications. The result? A 30% drop in serious adverse drug reactions. That’s not a small gain. That’s life-changing.

What made this study different? It wasn’t done after someone got sick. It was done before any drug was prescribed. That’s called preemptive testing. And it worked better than waiting for side effects to appear. Reactive testing - done after a reaction - only reduced ADRs by 15-20%. Preemptive testing cut it in half.

The panel used in the study covered genes tied to over 100 commonly used drugs: antidepressants, painkillers, blood thinners, chemotherapy agents, statins, and more. The results were fed directly into doctors’ electronic records. When a doctor tried to prescribe a drug that clashed with a patient’s genes, the system flagged it. No more missed warnings.

Which Drugs and Genes Matter Most?

Not every drug needs genetic testing. But for some, it’s critical. Here are the top five gene-drug pairs with the strongest evidence:

- CYP2C19 + Clopidogrel: Poor metabolizers get no benefit. Alternative drugs like prasugrel are needed.

- TPMT + Azathioprine/6-MP: Low enzyme activity causes life-threatening drops in white blood cells. Dose reduction cuts risk by 78%.

- HLA-B*1502 + Carbamazepine: Avoid this drug entirely in carriers. Use lamotrigine or valproate instead.

- SLCO1B1 + Simvastatin: High risk of muscle damage. Switch to pravastatin or rosuvastatin if you’re at risk.

- DPYD + Fluorouracil (5-FU): A deadly reaction in cancer patients. Testing prevents fatal toxicity.

These aren’t edge cases. They’re common. In fact, the PREPARE study found that 93.5% of people had at least one gene variant that affected how they responded to a medication. That means almost everyone has a genetic reason to be cautious with at least one drug.

How Testing Is Done - And How Fast

Getting tested is simple. A cheek swab or blood sample is taken. No fasting. No needles unless you’re already getting blood drawn. The sample goes to a lab that uses genotyping arrays to read specific variants - not your whole genome. The test looks for known, clinically relevant changes in 12-20 genes. Results come back in 24 to 72 hours.

Modern labs can test for 50+ variants with 99.9% accuracy. The cost? Around £150-£350 in the UK, depending on the panel. That’s less than a single hospital admission for an ADR. And it’s often covered by the NHS for high-risk cases like cancer or heart disease.

The real challenge isn’t the test. It’s the system. Results need to be integrated into electronic health records. Doctors need alerts. Pharmacists need access. Without that, the test sits on a shelf - useless.

Why Isn’t Everyone Getting Tested?

If it works so well, why isn’t it standard? Three big reasons.

First, many doctors don’t know how to use the results. A 2022 survey found only 37% of physicians felt confident interpreting pharmacogenetic reports. That’s changing, but slowly. Training programs are being rolled out, but they’re not yet mandatory.

Second, polypharmacy makes things messy. If you’re on six drugs, and three of them interact with your genes, the advice isn’t always clear-cut. Should you stop one? Switch one? Adjust the dose? The guidelines exist - from CPIC and DPWG - but they’re complex. Not every clinic has a clinical pharmacist trained in pharmacogenomics to help sort it out.

Third, access isn’t equal. Most genetic data comes from people of European descent. Variants common in African, South Asian, or Indigenous populations are still under-studied. That means test results for these groups can be less accurate. The NIH and European research programs are now funding studies to fix this gap - but it’s a work in progress.

What’s Next? The Future of Drug Safety

The future isn’t just about single genes. Researchers are now building polygenic risk scores - combining dozens of small genetic effects to predict how someone will respond to a drug. Early studies show these scores improve prediction accuracy by 40-60% over single-gene tests.

Point-of-care testing is coming too. Imagine a doctor’s office running a quick PCR test in 20 minutes - like a rapid strep test - and adjusting your prescription right then and there. Pilot projects suggest this could cut costs to under £50 per test by 2026.

The FDA has updated its list of gene-drug pairs to 329. The European Commission is investing €150 million to roll out preemptive testing across member states by 2027. In the U.S., Medicare already covers testing for clopidogrel and thiopurines. The UK’s NHS is quietly expanding its pilot programs.

This isn’t science fiction. It’s happening now.

What You Can Do Today

If you’re on multiple medications - especially for heart disease, depression, cancer, or chronic pain - ask your doctor: "Could my genes affect how I respond to these drugs?"

If you’ve had an unexpected side effect - like unexplained muscle pain on statins, severe nausea on chemotherapy, or a rash after carbamazepine - ask if pharmacogenetic testing could explain it. That information could save your life next time.

Don’t wait for a crisis. If you’re planning to start a new long-term medication, request a test. It’s not expensive. It’s not invasive. And it’s one of the most effective ways to make sure your next prescription doesn’t hurt you.

The goal isn’t to replace doctors. It’s to give them better tools. The goal isn’t to predict everything. It’s to prevent the worst.

FAQ

Is pharmacogenetic testing covered by the NHS?

Yes, but only for specific high-risk situations. The NHS currently covers testing for TPMT before azathioprine use, CYP2C19 before clopidogrel in heart patients, and DPYD before fluorouracil chemotherapy. Broader preemptive testing is still in pilot phases, but expansion is underway. If your doctor believes you’re at risk, they can request it.

Can I get tested without a doctor’s order?

Direct-to-consumer tests like 23andMe can show some gene variants, but they’re not designed for clinical use. They often miss key variants or misinterpret results. For accurate, actionable results, you need a test ordered by a clinician and interpreted through clinical guidelines (like CPIC or DPWG). Self-testing without medical support can be misleading and dangerous.

Does pharmacogenetic testing reveal information about my ancestry or disease risk?

No. The tests used for drug safety focus only on variants known to affect drug metabolism or risk of specific reactions. They do not screen for conditions like Alzheimer’s, cancer predisposition, or ancestry. Your genetic privacy is protected - the results are only used to guide medication choices.

How long do the results last?

Forever. Your genes don’t change. Once you’ve been tested, the results are valid for life. That’s why preemptive testing is so powerful - you only need to do it once. The results can be reused for every new prescription you receive, making it a one-time investment with lifelong benefits.

Are there any risks to getting tested?

The physical risk is zero - it’s just a cheek swab or blood draw. The main risk is misunderstanding the results. A variant doesn’t mean you can’t take a drug - it means you might need a different dose or alternative. Without proper interpretation, you might avoid a necessary medication unnecessarily. That’s why results should always be reviewed with a healthcare provider trained in pharmacogenomics.

What if my doctor says pharmacogenetic testing isn’t necessary?

You can ask for a referral to a clinical pharmacist or pharmacogenomics specialist. Many hospitals now have these roles. You can also request a copy of your results to share with future providers. The PREPARE study showed that even in systems with low physician awareness, testing still reduced ADRs - so your advocacy matters. Don’t accept "we’ve always done it this way" as an answer when science offers a safer path.

12 Comments

Shannara Jenkins

This is the kind of info every patient should know. I’ve been on statins for years and never knew my muscle pain might’ve been genetic. Finally, medicine is catching up with biology.

Jay Everett

Finally! Someone who gets it. 😊 I’ve been screaming about this since med school - we’re still treating people like they’re all made from the same Lego set. Your genes aren’t a suggestion, they’re the instruction manual. And yeah, 93.5% of us have at least one red flag. That’s not rare - that’s the norm. Let’s stop pretending random dosing is science.

Paul Keller

The PREPARE study’s findings are nothing short of revolutionary. The notion that a single, low-cost genetic test can reduce adverse drug reactions by 30% fundamentally undermines the entire paradigm of empirical prescribing. One-size-fits-all medicine is not merely outdated - it is ethically indefensible when evidence-based alternatives exist. The systemic inertia preventing universal adoption is not a technical failure but a moral one. We are knowingly exposing patients to preventable harm because of bureaucratic inertia and physician ignorance. This is not innovation lagging - this is negligence masquerading as tradition.

Jack Dao

Oh wow, another ‘genetics will fix everything’ fairy tale. 😒 Next you’ll tell me we should test for ‘good taste in music’ before prescribing Taylor Swift. Look, I get it - science is cool. But most docs don’t even know how to spell ‘CYP2D6,’ let alone interpret it. And yeah, 93.5% of people have a variant? So what? Most of them don’t even take drugs that matter. Stop hyping up hype.

Ella van Rij

So... I paid $300 for 23andMe and now I know I’m a slow CYP2C19 metabolizer? Cool. Now what? My doctor laughed and said ‘just take less.’ 🤦♀️ Thanks for the $300 reminder that I’m basically a lab rat with a credit card.

मनोज कुमार

CYP2C19 poor metabolizer 30% population. TPMT fatal myelosuppression. HLA-B*1502 high risk in Asians. PREPARE study 30% ADR reduction. NHS covers few. Access inequity. Polypharmacy complexity. Clinical guidelines exist but underutilized. Done.

Elizabeth Grace

I had a rash on carbamazepine and they just said ‘weird coincidence.’ Now I know it could’ve killed me. I’m getting tested before my next script. My mom’s on 7 meds - she deserves this too. 🤍

dave nevogt

It’s strange, isn’t it? We spend billions on drugs that work for some and harm others, yet we refuse to look at the one thing that’s always consistent - the human genome. We treat biology like it’s a black box, when in fact, it’s written in code. We’ve mapped the human genome, but we still prescribe like we’re guessing in the dark. Maybe the real question isn’t why we don’t test more - but why we still believe randomness is acceptable in medicine. The answer isn’t in the lab. It’s in our willingness to accept that we don’t know everything - and that we never really did.

Steve Enck

While the PREPARE study demonstrates statistically significant reductions in adverse drug reactions, one must critically interrogate the underlying epistemological assumptions. The conflation of genetic determinism with clinical utility risks reifying biological reductionism as therapeutic omniscience. Furthermore, the absence of longitudinal data on cost-benefit ratios across diverse socioeconomic strata renders generalizability questionable. The algorithmic integration of pharmacogenomic data into EHRs, while technologically plausible, introduces new vectors of diagnostic misattribution - particularly when polygenic interactions remain poorly characterized. One must ask: are we advancing patient safety, or merely automating ignorance with a genomic veneer?

Alicia Marks

Just asked my pharmacist about testing - she said it’s covered for my antidepressant. Made the request. Felt like I finally took control. You don’t need to be a genius to ask this question. Just care enough to try.

Joel Deang

bro i got my 23andme results and it said im a slow CYP2D6 metabolizer so i stopped my pain meds... then i got a headache and cried for 3 hours. maybe dont trust the internet lol 🤷♂️

Shannara Jenkins

That’s exactly why you need a doctor to interpret it. My cousin did the same thing - thought ‘slow metabolizer’ meant ‘don’t take it.’ Turns out, she just needed a lower dose. The test isn’t a yes/no switch - it’s a dimmer. Talk to someone who knows how to turn it.