When you walk into a pharmacy in the U.S. and see a $6 copay for a 30-day supply of metformin, it’s easy to think: generic drugs are cheap here. And you’re right - for the most part. But if you’ve ever wondered why Americans pay so much more for brand-name pills like Humira or Jardiance while paying less for generics than people in Europe or Japan, the answer isn’t simple. It’s a story of two markets inside one country: one where prices are slashed by competition, and another where they’re inflated by negotiation gaps and global pricing asymmetries.

Generics in the U.S. Are Actually Cheaper Than Almost Everywhere Else

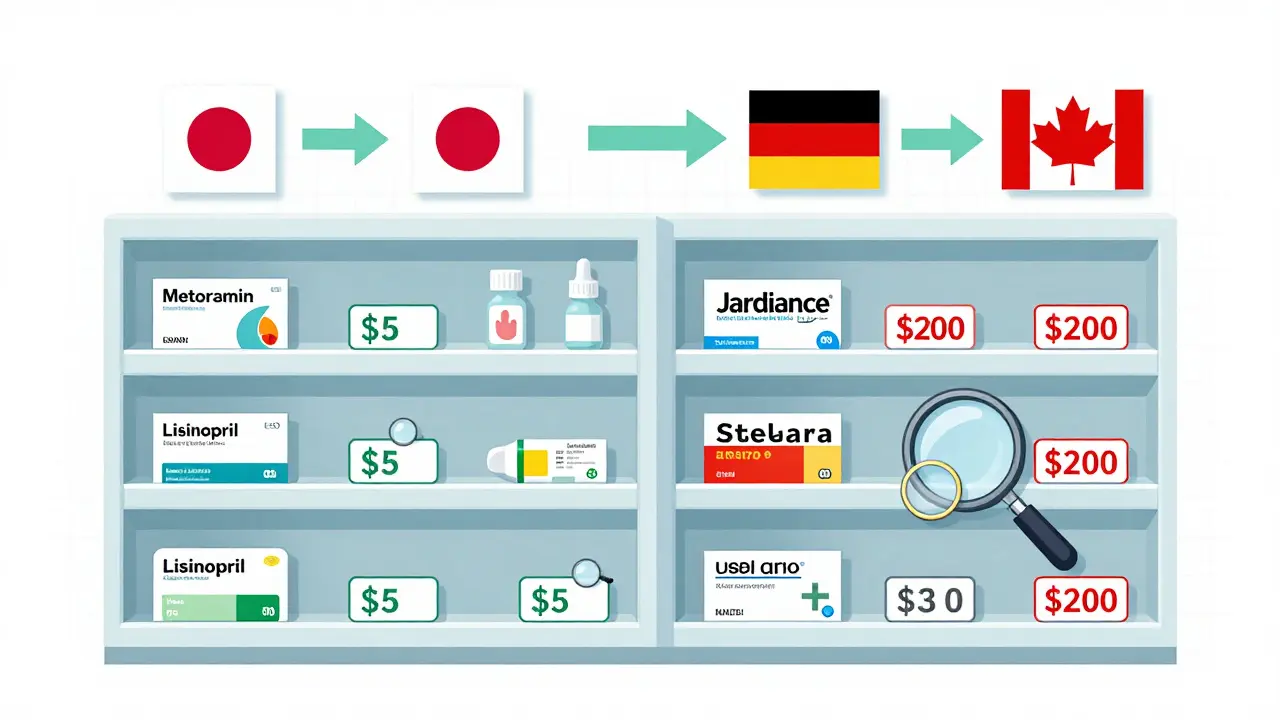

Here’s the surprise: the U.S. doesn’t have the most expensive generic drugs. In fact, it has some of the cheapest. According to a 2022 RAND Corporation study for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. prices for unbranded generic drugs were 33% lower than in 33 other developed countries. That means if a generic version of lisinopril costs $5 in Germany, you’ll likely pay $3.35 in the U.S. - and often even less.

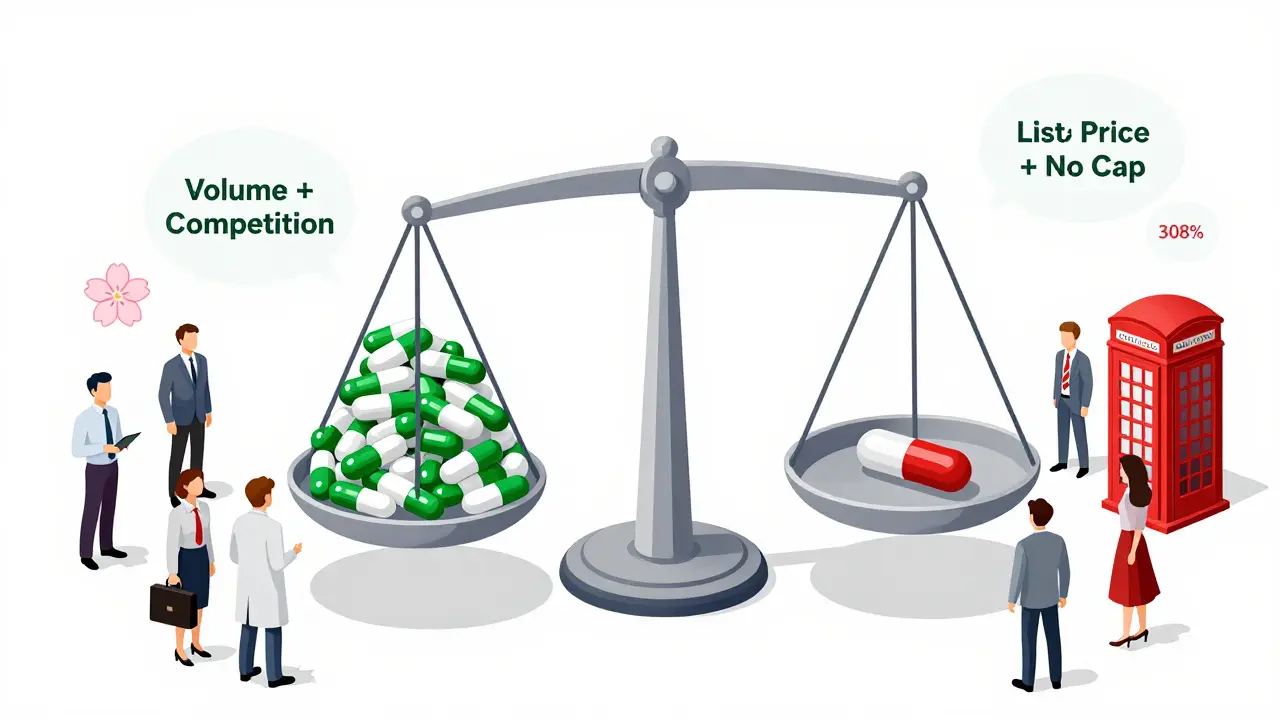

Why? Volume and competition. The U.S. fills 90% of its prescriptions with generics - far more than anywhere else. In Canada, it’s about 41%. In France, it’s 55%. More prescriptions mean more buyers, and more buyers mean more manufacturers want in. When three or more companies start making the same generic drug, prices drop to 15-20% of the original brand’s cost. The FDA found that when a second generic enters the market, prices fall by 50%. With a third, they drop another 60%.

Take amoxicillin. In 2023, the average U.S. wholesale price for a 500mg capsule was $0.03. In the UK, it was $0.06. In Australia, $0.07. In Japan, $0.08. The U.S. isn’t just cheaper - it’s dramatically cheaper. And that’s not an accident. It’s the result of a system built for scale: pharmacies, insurers, and Medicare all push for the lowest possible price because they buy in bulk.

Brand-Name Drugs Are Where the Real Price Shock Happens

But here’s the flip side: if you need a brand-name drug, you’re paying more than almost anyone else on Earth. The same RAND study found that U.S. prices for brand-name drugs were 308% higher than the OECD average. For originator drugs - the very first version released by the manufacturer - U.S. prices were over four times higher than elsewhere.

Compare this: Jardiance, a diabetes drug made by Boehringer Ingelheim, costs $52 per month in Japan. In the U.S., Medicare negotiated a price of $204 - nearly four times as much. Stelara, a psoriasis treatment, costs $2,822 in the U.K. and $4,490 under Medicare. In Germany, it’s $2,700. In Canada, $3,100. The U.S. isn’t just paying more - it’s paying 2 to 4 times more for the same pill.

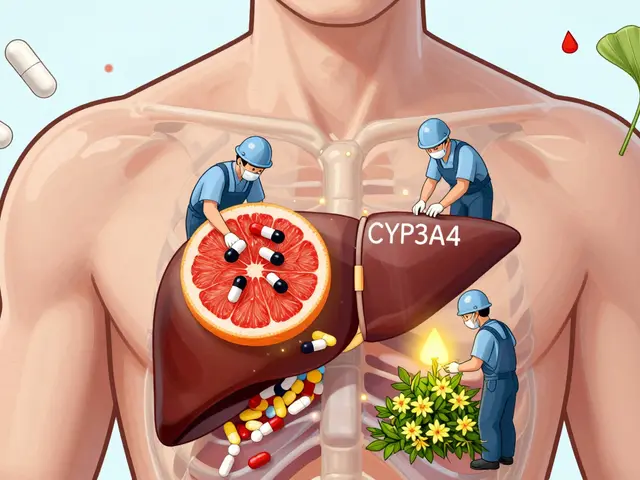

This isn’t because U.S. drug companies are greedy (though some are). It’s because the U.S. doesn’t negotiate prices the way other countries do. In Canada, France, and the U.K., the government sets a maximum price based on what it thinks the drug is worth. In the U.S., drugmakers set list prices - and then offer massive rebates to insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). That’s why the real price you pay at the counter doesn’t reflect the sticker price.

The List Price vs. Net Price Confusion

Here’s where things get tricky. When people say “U.S. drug prices are 2.78 times higher than other countries,” they’re talking about list prices - the price before any discounts. But that’s not what most Americans actually pay. The University of Chicago’s Energy Coalition and Climate Hub found that net prices - after rebates, discounts, and government negotiations - are actually 18% lower in the U.S. than in Canada, Germany, the U.K., France, and Japan.

How? Because Medicare Part D and Medicaid negotiate hard. In 2023, the average generic copay was $6.16. The average brand-name copay? $56.12. And 93% of generic prescriptions cost under $20. For brand names? Only 59% did. That’s why your out-of-pocket cost for a generic might be $3 - even if the list price was $50. The difference goes to the PBM, the insurer, and the pharmacy. You never see it.

But here’s the catch: if you don’t have insurance, or if you’re paying cash, you’re stuck with the full list price. That’s where the U.S. looks horrifying. A 30-day supply of insulin without insurance can cost $300. In Germany, it’s $12. In Australia, $15. In Japan, $10. So your experience depends entirely on your coverage - and your luck.

Why Do Other Countries Pay Less?

Other countries don’t have a free-market drug pricing system. They have price controls. The government says: “This drug is worth $X. We’ll pay that. If you want to sell it here, you accept it.” That’s why France and Japan have the lowest prices overall. Their systems are designed to keep costs down - even if it means slower access to new drugs.

The U.S. system is the opposite. It lets companies set high prices to fund research. The idea is: if you charge more here, you can afford to invent new drugs for everyone. That’s why so many new cancer drugs and rare disease treatments launch first in the U.S. But it also means Americans shoulder the cost of global innovation.

Some experts argue this isn’t fair. Dr. Dana Goldman from USC says: “Americans do quite well in the generic market.” But Dr. Andrew Mulcahy from RAND adds: “U.S. gross prices are higher for brand-name drugs - and that’s the problem.” Both are right. It’s not one system. It’s two.

What’s Changing in 2025?

In 2022, Congress gave Medicare the power to negotiate prices for 10 high-cost drugs. The first round was finalized in 2024. The results? Medicare’s negotiated prices were still 2.8 times higher than the average in 11 other countries. Only one drug - Stelara - was priced lower in Germany than in the U.S. Medicare’s price for Jardiance? $204. Japan’s price? $52.

By February 2025, 15 more drugs will be added to the negotiation list. That includes drugs like Farxiga, Ozempic, and Enbrel. Will those prices drop? Yes - but they’ll still be higher than what other countries pay. The goal isn’t to match global prices. It’s to bring U.S. prices down from their current sky-high levels.

Meanwhile, the FDA approved 773 new generic drugs in 2023. That’s expected to save $13.5 billion over five years. More generics = lower prices. More competition = faster drops. But it takes time. A new generic can take 12-24 months to hit the market after patent expiry. And sometimes, manufacturers don’t enter - leaving the field open for one company to jack up prices. That’s how you get a $500 generic version of a drug that should cost $10.

What This Means for You

If you take generics - and most people do - you’re getting a great deal. The U.S. is the best place in the world to buy common medications like atorvastatin, levothyroxine, or sertraline. You pay less than people in Australia, Germany, or Canada.

If you need a brand-name drug - especially for chronic conditions like diabetes, RA, or cancer - you’re paying more than almost anyone else. And if you’re uninsured, you’re in a dangerous spot. That’s why shopping around matters. Use GoodRx. Compare prices at Walmart, Costco, and your local pharmacy. Some generics cost $4 at Walmart and $40 at your local chain.

Policy changes are coming. But they won’t fix everything. The U.S. will still pay more for innovation. But for the 90% of prescriptions that are generics? You’re already winning.

Where the U.S. Stands: A Quick Snapshot

| Drug Type | U.S. Average Price | Japan | France | Germany | Canada | UK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic Lisinopril (10mg, 30 tablets) | $3.50 | $5.20 | $4.80 | $5.10 | $6.30 | $4.90 |

| Generic Metformin (500mg, 60 tablets) | $4.20 | $6.80 | $5.50 | $6.10 | $7.40 | $5.70 |

| Brand Jardiance (10mg, 30 tablets) | $204 | $52 | $87 | $91 | $128 | $105 |

| Brand Stelara (90mg injection) | $4,490 | $2,700 | $3,100 | $2,822 | $3,500 | $3,200 |

Bottom line: the U.S. is a paradox. It’s the cheapest place in the world to buy generic drugs - and the most expensive to buy brand-name ones. The system works well for the 90% of prescriptions that are generics. It fails the 10% that aren’t.

How to Save on Medications Right Now

- Always ask if a generic is available - even if your doctor didn’t suggest it.

- Use GoodRx or SingleCare to compare prices across pharmacies. Prices can vary by 500% for the same drug.

- Check Walmart, Costco, and Target. Their generic lists are often under $5 for 30-day supplies.

- If you’re on Medicare, check if your drug is in the negotiation list. You might pay less next year.

- Don’t assume insurance always saves you. Cash prices for generics are sometimes lower than your copay.

Why are generic drugs cheaper in the U.S. than in other countries?

The U.S. has a massive volume of generic prescriptions - 90% of all fills - which attracts dozens of manufacturers. When three or more companies make the same drug, prices drop to 15-20% of the brand price. Other countries have fewer generics, less competition, and government price controls that set higher minimums. The U.S. system rewards volume and competition; others prioritize stability and predictable revenue for manufacturers.

Are U.S. brand-name drug prices really that much higher?

Yes. For originator drugs, U.S. list prices are over 4 times higher than in Japan, France, and Germany. Even after rebates, Medicare’s negotiated prices for top drugs are still 2-4 times higher than international averages. The U.S. doesn’t regulate prices like other countries - it lets companies set them, then negotiates behind the scenes. That’s why the sticker price is so high, even if you don’t pay it.

Can I buy generic drugs from other countries to save money?

Technically, importing prescription drugs from Canada or other countries is illegal under U.S. law, though enforcement is rare for personal use. Some Americans do it - especially for insulin or heart meds - and report savings of 70-90%. But there’s risk: no FDA oversight, potential counterfeits, and no recourse if something goes wrong. It’s not recommended, but it’s a reality for many who can’t afford U.S. prices.

Why doesn’t the U.S. just cap drug prices like other countries?

Because the U.S. pharmaceutical industry argues that high prices fund innovation. Most new drugs - especially for cancer, rare diseases, and autoimmune conditions - are developed in the U.S. If prices were capped like in Europe, companies say they wouldn’t invest as much in R&D. There’s truth to that: 70% of global drug innovation comes from U.S. companies. But critics say other countries pay less because they negotiate harder, not because they don’t value innovation.

What’s the future of drug pricing in the U.S.?

More generics. More Medicare negotiations. And more pressure to bring brand-name prices down. The 2025 expansion of Medicare’s negotiation program will affect 15 more drugs, likely lowering costs for seniors. But unless the U.S. changes how it sets list prices, brand-name drugs will remain far more expensive than elsewhere. For generics? The trend is clear: prices will keep falling as more manufacturers enter the market.

What’s Next?

If you’re on a fixed income or managing chronic illness, the gap between generic and brand-name pricing is life-changing. The U.S. system gives you incredible savings on common meds - but leaves you vulnerable when you need something new. Keep an eye on the FDA’s monthly updates on generic approvals. Every new generic that hits the market is a chance to save hundreds. And always, always ask: “Is there a cheaper version?” That one question could cut your bill in half.

15 Comments

Patrick Roth

Wow, so the U.S. is cheap for generics but a scam for brands? Newsflash - that’s not a paradox, it’s capitalism with a side of corporate greed. You think the FDA’s approving 773 generics in a year is a win? Nah, it’s just the system letting the bottom feeders fight over crumbs while the big pharma CEOs take the whole damn buffet.

Lana Kabulova

Wait-so if I’m uninsured and need insulin, I pay $300… but if I’m on Medicare, I pay $204 for Jardiance? So the system’s designed to punish the poor and reward the elderly? That’s not healthcare. That’s a rigged game where the house always wins. And don’t even get me started on PBMs… they’re the real villains. No one talks about them. But they’re the ones pocketing the rebates. You’re paying more because someone else’s middleman is rich.

Rob Sims

Oh wow, so the U.S. pays more for brand drugs because we ‘fund global innovation’? That’s the same excuse they used for the Iraq War. ‘We’re doing it for freedom.’ No. You’re doing it because you can. And the rest of the world is just too polite to say ‘you’re getting ripped off.’ If you’re a U.S. citizen and you believe this narrative, you’re either brainwashed or you’re on Big Pharma’s payroll. Either way, stop pretending this is fair.

arun mehta

🙏 Truly eye-opening post! 🌍 The U.S. generic drug system is a marvel of market efficiency - 90% penetration, fierce competition, prices slashed by volume. Meanwhile, in India, we struggle with access even for generics due to supply chain gaps. But I must say - the brand-name disparity is heartbreaking. We produce 40% of the world’s generics - yet our people pay more per pill than Americans. The irony is not lost. Kudos to the U.S. for making generics affordable. But the brand-name gap? That’s a moral crisis. 🙏 Let’s fix both sides.

Chiraghuddin Qureshi

India makes 40% of the world’s generics - yet Americans pay less for them than we do. 🤯 That’s the global economy for you. I’ve bought metformin in Delhi for ₹15 ($0.18) - and I still pay $4.20 here. Why? Because U.S. pharmacies buy in bulk from Indian factories and then slap on a ‘distribution fee.’ The system’s rigged, but at least the pills are real. 🇮🇳🇺🇸

Lauren Wall

So the U.S. is cheap on generics because we have no price controls? That’s not a feature - it’s a flaw. Other countries pay more because they care about sustainability. We pay less because we don’t care who goes bankrupt making the pills. And now we’re proud of it? That’s not innovation. That’s exploitation dressed up as efficiency.

Kenji Gaerlan

generic drugs are cheap? yeah right. i got my lisinopril at walmart for $4. but my friend paid $38 at cvs. so what? the system is broken. who even knows what’s going on anymore? i just take my pills and hope i dont die. also, why is everyone so mad? its just medicine. chill.

Oren Prettyman

Let us be clear: the notion that the U.S. is ‘the cheapest’ for generics is statistically misleading. The RAND study compares wholesale prices, not out-of-pocket costs - and it excludes the hidden costs of insurance premiums, deductibles, and formulary restrictions. Moreover, the 90% generic utilization rate is not a sign of efficiency - it is a sign of desperation. When your formulary only covers generics, you don’t have a choice. You are not ‘winning.’ You are being forced into a low-cost, low-quality tier of care. The fact that you are proud of this is the true tragedy.

Tatiana Bandurina

It’s not about price. It’s about control. The U.S. doesn’t negotiate - it manipulates. The ‘net price’ is a fiction created by PBMs who take 20-30% of the rebate. The pharmacy gets pennies. The manufacturer gets a tax write-off. The patient? They’re just a number in a spreadsheet. And if you think Medicare’s ‘negotiation’ is real - check the prices. They’re still 2-4x higher than everywhere else. This isn’t reform. It’s theater.

Philip House

People say ‘Americans pay more for innovation.’ But who invented innovation? Not you. Not me. It was a bunch of scientists in labs funded by U.S. tax dollars, NIH grants, and venture capital - all of which come from the same system that lets drug companies charge $200 for a pill. So we pay twice: once in taxes, once at the pharmacy. Meanwhile, Europe just steals the R&D and caps the price. That’s not fair. That’s theft. And we’re the suckers who fund the whole damn world.

Akriti Jain

Did you know the FDA approves generics from factories in China that have never been inspected? 🤫 Big Pharma owns the inspectors. The ‘cheap generics’? They’re made in the same factories that made the tainted heparin in 2008. The ones that caused 80 deaths. But hey - $3.50 for lisinopril, right? You’re saving money. But your kidneys? They’re on vacation. And the ‘competition’? Only 3 companies make metformin - and they all colluded in 2021. Price-fixing. All legal. Welcome to America.

Mike P

Look - if you’re taking metformin and paying $4, you’re winning. End of story. The rest of this is just rich people complaining because they can’t get their $10,000 cancer drug for $500. We’re not Europe. We don’t do ‘fair.’ We do ‘get it done.’ And yeah, if you’re uninsured and need insulin - that’s tragic. But don’t blame the system. Blame the fact that you didn’t plan ahead. Life’s not fair. But your generic blood pressure pill? It’s cheaper than your coffee. Be grateful.

Jasmine Bryant

I just wanted to add - if you’re on Medicare and your drug is on the negotiation list, check your plan’s formulary every year. Some drugs dropped off in 2024 and prices jumped. Also, GoodRx sometimes shows lower cash prices than your copay - especially if you’re on a high-deductible plan. I saved $80 on my statin last month just by switching pharmacies. It’s annoying, but it works. And yes - Walmart’s $4 list is real. I’ve bought 6 months’ worth.

Liberty C

How delightful. A nation that treats its citizens like disposable widgets, then celebrates the fact that its pharmaceutical oligarchs have turned the most basic human need - medicine - into a carnival of price gouging. We don’t have a healthcare system. We have a performance art piece titled ‘Capitalism: The Musical.’ And the audience? The sick, the elderly, the uninsured - all forced to buy tickets at the front row while the executives sip champagne in the VIP section. Bravo. Encore.

shivani acharya

Let’s be real - the whole thing is a psyop. The FDA approves generics from China, but only after they pass a ‘quality check’ that’s done by a contractor hired by the drug company. The ‘price drops’? They’re fake. The companies just stop making the cheap version, wait a few months, then re-release it as a ‘new formulation’ with a 200% markup. And the ‘competition’? Three companies control 85% of the market - they’re all owned by the same parent company in Switzerland. You think you’re saving money? You’re being played. And the government? They’re in on it. The ‘negotiations’? A joke. Medicare pays $204 for Jardiance? That’s what they want you to think. The real price? $80. The rest? Goes to lobbyists. And the FDA? They’re just the front desk for Big Pharma.