More than 80% of kids will have at least one middle ear infection by the time they turn three. It’s one of the most common reasons parents take their child to the doctor. But here’s the thing: antibiotics aren’t always the answer.

What Exactly Is Otitis Media?

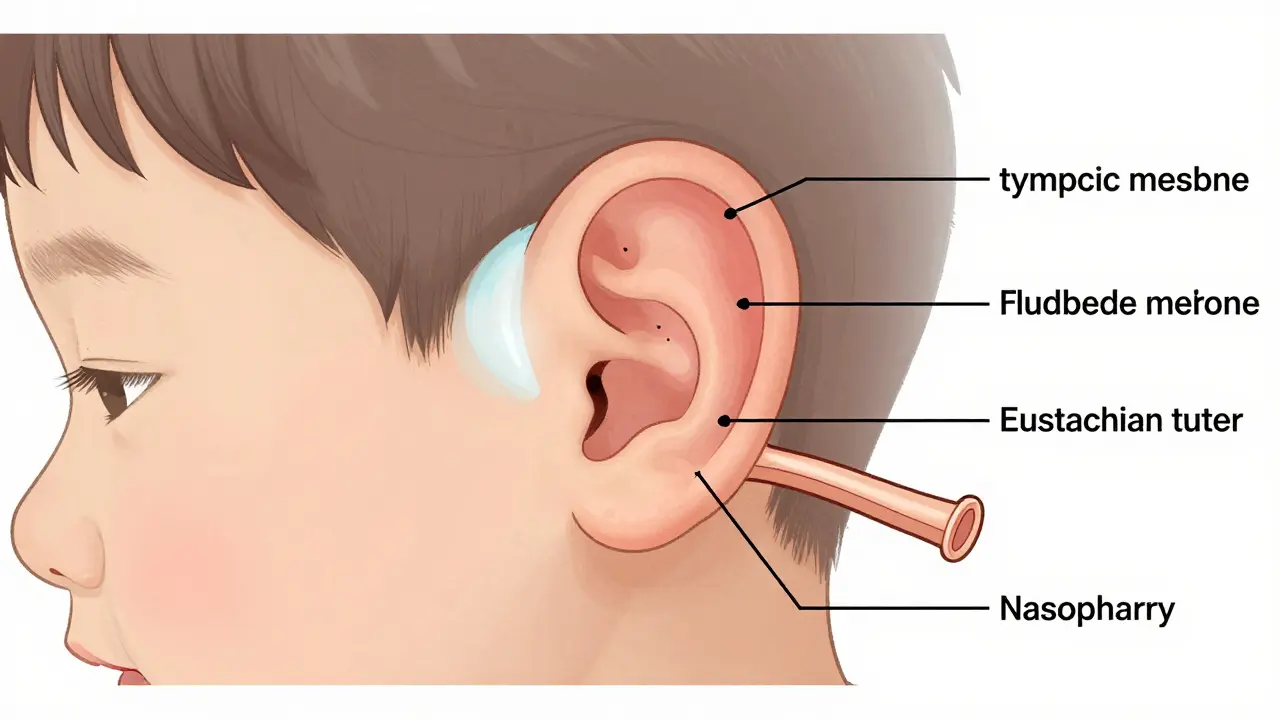

Otitis media means inflammation or infection in the middle ear - the space behind the eardrum. It’s not just an earache. It’s fluid building up where it shouldn’t be, often because the Eustachian tube (the little channel that drains fluid from the ear to the throat) gets blocked. That happens after a cold, allergies, or a respiratory infection. In kids, this tube is shorter, more horizontal, and doesn’t work as well as in adults. That’s why babies and toddlers are so much more likely to get ear infections.The infection can be viral or bacterial. Common culprits include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Viruses like RSV, rhinovirus, and even some coronaviruses can trigger it too. You’ll know it’s active when the eardrum looks red, swollen, and bulging - something a doctor checks with a special tool called a pneumatic otoscope.

Why Antibiotics Aren’t Always Needed

Here’s what most people don’t realize: about 80% of uncomplicated middle ear infections clear up on their own within three days. That’s not a guess. It’s backed by data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the CDC. For many kids - especially those over two years old with mild symptoms - waiting it out is not just safe, it’s smarter.Antibiotics don’t speed up recovery in most cases. They just add risk: diarrhea in 10-25% of kids, rashes, upset stomachs, and the bigger problem - antibiotic resistance. Every time we use them unnecessarily, we make future infections harder to treat. The CDC says nearly half of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains in the U.S. are now resistant to penicillin. That’s why guidelines now push for watchful waiting in low-risk cases.

When Do You Actually Need Antibiotics?

There are clear situations where antibiotics are necessary:- Children under 6 months old with confirmed infection

- Kids 6 to 23 months with severe symptoms - fever over 39°C (102.2°F) or ear pain lasting more than 48 hours

- Children 2 years and older with severe pain or high fever

- Any child with a ruptured eardrum and pus draining out

- Children with underlying conditions like immune problems or cleft palate

For most others - especially older kids with mild fever and ear discomfort - doctors are increasingly recommending 48 to 72 hours of pain control before deciding on antibiotics. If symptoms don’t improve or get worse, then it’s time to start treatment.

What Antibiotics Are Used - and Why

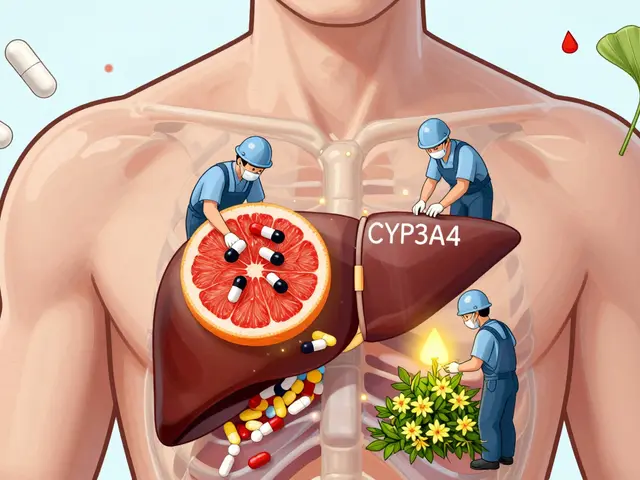

If antibiotics are needed, amoxicillin is still the first choice. The dose is high - 80 to 90 mg per kg of body weight, split into two doses a day. That’s higher than what was used 10 years ago because of rising resistance. For kids under two with bilateral infections, a full 10-day course is standard. For older kids with mild cases, 5 to 7 days is often enough.If your child is allergic to penicillin, alternatives include:

- Cefdinir - an oral cephalosporin

- Ceftriaxone - a single shot, good if swallowing pills is hard

- Azithromycin - a 5-day course, used when other options aren’t suitable

Amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin) is often prescribed when the infection doesn’t improve with amoxicillin alone, or if there’s a history of recurrent infections. But even that’s becoming less effective - resistance in Haemophilus influenzae has jumped from 7% in 2010 to over 12% by 2022.

Pain Management Is the Real First Step

The most important thing you can do at the start? Control the pain. A child with a bad ear infection is miserable. Fever, crying, trouble sleeping - it’s all unbearable.Acetaminophen (10-15 mg/kg every 4-6 hours) or ibuprofen (5-10 mg/kg every 6-8 hours) are the go-to options. Many parents swear by ibuprofen - it reduces inflammation and lasts longer. A warm compress on the ear can help too. Some doctors recommend ear drops like Auralgan for pain, but never use them if you suspect the eardrum has burst. You’ll know that if there’s sudden drainage of yellow or bloody fluid - that’s a sign the pressure released.

One parent on Reddit shared: “Ibuprofen every 6 hours turned my screaming 18-month-old into a sleepy, calm kid. We waited 48 hours. No antibiotics needed.”

Red Flags That Mean You Need to Act Fast

Watchful waiting doesn’t mean ignoring warning signs. If your child has any of these, don’t wait:- Fever above 104°F (40°C)

- Severe pain that doesn’t respond to painkillers

- Drainage of pus or blood from the ear

- Dizziness, vomiting, or trouble balancing

- Facial weakness or drooping

- Extreme lethargy or confusion

These could mean the infection has spread - to the mastoid bone behind the ear, or even to the brain. That’s rare, but serious. If you see any of these, go to urgent care or the ER.

What About Fluid That Lingers?

Sometimes, after the infection clears, fluid stays behind the eardrum. That’s called otitis media with effusion (OME). It’s not an active infection. No fever, no pain. But it can cause temporary hearing loss - usually 15 to 40 decibels. That means your child might not hear soft speech or respond when called from another room.Here’s the good news: in 90% of cases, that fluid goes away on its own within 3 months. Antibiotics won’t help. Decongestants and antihistamines don’t work either. The only time surgery is considered is if the fluid lasts longer than 3 months and is affecting speech or learning. Then, tiny tubes might be placed in the eardrums to drain the fluid.

Vaccines Can Prevent Ear Infections

One of the most effective ways to reduce ear infections? Vaccines. The pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13 and now PCV15) cuts vaccine-type pneumococcal ear infections by 34%. That’s not a small number. It’s a game-changer. The flu shot also helps - since flu often leads to ear infections. If your child hasn’t had these vaccines, talk to your doctor. Prevention beats treatment every time.Why Some Parents Feel Stuck

Not everyone agrees on watchful waiting. Some parents feel pressured to get antibiotics because they’re exhausted. Others worry they’re being negligent if they don’t treat it right away. One mother in Ohio wrote on Healthgrades: “We waited three days. Then our 2-year-old spiked 104°F and ended up in the ER with a ruptured eardrum. I wish we’d started antibiotics sooner.”But here’s the flip side: another parent on Reddit said, “We held off. No antibiotics. Kid was fine in 72 hours. No diarrhea, no resistance, no fuss.”

The truth is, outcomes vary. Some kids bounce back fast. Others need help. That’s why it’s critical to have a clear plan with your doctor - not just a prescription handed out on autopilot.

The Bigger Picture: Costs, Resistance, and Future Tools

Otitis media leads to over 15 million doctor visits in the U.S. every year. That’s $2.9 billion in direct costs. About 15 million antibiotic prescriptions are written annually for ear infections - second only to sore throats. But with resistance rising, we’re running out of easy fixes.There’s hope on the horizon. New tools like the CellScope Oto - a smartphone attachment that lets parents take pictures of the eardrum and send them to a doctor - are improving accuracy and reducing unnecessary visits. In-office tympanometry (a test that measures eardrum movement) has already cut antibiotic use by 22% in some clinics. In the next five years, point-of-care tests that identify the exact bacteria causing the infection could reduce broad-spectrum antibiotic use by 30-40%.

For now, the best approach is simple: treat pain first, wait 48-72 hours if symptoms are mild, and only use antibiotics when they’re truly needed. Your child’s body is capable of fighting off many infections - especially when you give it time and support.

Do all ear infections need antibiotics?

No. About 80% of middle ear infections in children resolve on their own within 3 days without antibiotics. Antibiotics are only recommended for infants under 6 months, children with severe symptoms (high fever or intense pain lasting more than 48 hours), or those at higher risk for complications.

Is amoxicillin the best antibiotic for ear infections?

Yes, for most cases. High-dose amoxicillin (80-90 mg/kg/day) is the first-line treatment because it’s effective against the most common bacteria and has a good safety profile. If your child is allergic to penicillin, alternatives like cefdinir, ceftriaxone, or azithromycin are used.

How long should antibiotics be taken for an ear infection?

For children under 2, a full 10-day course is standard. For kids 2 to 5 with severe symptoms, 7 days is typical. For children 6 and older with mild infections, 5 to 7 days is often enough. Shorter courses reduce side effects and help fight antibiotic resistance.

Can ear infections cause hearing loss?

Yes - temporarily. During an active infection, fluid behind the eardrum can cause mild conductive hearing loss (15-40 decibels), making soft sounds hard to hear. This usually clears up once the infection resolves. If fluid stays for more than 3 months, it can affect speech development, and a doctor may recommend ear tubes.

What can I do at home to help my child’s ear infection?

Use acetaminophen or ibuprofen for pain and fever. Apply a warm compress to the ear. Keep your child hydrated and rested. Avoid smoke exposure - it increases risk of infection. Never put drops in the ear if you suspect a ruptured eardrum. Monitor for red flags like high fever, pus drainage, or dizziness.

How can I prevent future ear infections?

Vaccinate your child with PCV13 or PCV15 and the annual flu shot. Breastfeed if possible - upright feeding reduces risk. Avoid bottle-feeding while lying down. Keep your child away from secondhand smoke. Limit exposure to large daycare settings if infections keep recurring. Regular check-ups help catch early signs.

10 Comments

Paul Barnes

Let me just say this: the CDC’s own data shows 80% of otitis media cases resolve without antibiotics. Why do doctors still default to prescribing them? It’s not medical wisdom-it’s convenience. And parents? They’re just tired. But we’re not helping by normalizing overprescription. The math is clear: fewer antibiotics = less resistance. Period.

Andy Thompson

LOL 😂 so now we’re trusting big pharma’s ‘watchful waiting’ nonsense? Who’s really behind this? Big Pharma wants you to think antibiotics are bad so they can sell you $200 ‘natural ear drops’ or push those new $5000 ear tubes! They don’t want you to cure infections-they want you to pay for them forever! 🇺🇸 #BuyAmerican #AntibioticsAreSafe

sagar sanadi

Ha! Antibiotics bad? Then why in India we give amoxicillin for sneeze? Doctor say ‘take this, no wait’-then kid better or worse, still get bill. So here too? Just wait? What if kid deaf? Then who pay? 😒

kumar kc

Parents who delay treatment are playing Russian roulette with their child’s hearing. No excuses.

Thomas Varner

Okay, so… let’s just pause for a second… the fact that we’re even having this debate? Wild. We’ve got data, we’ve got guidelines, we’ve got parents who’ve been burned by both over-treatment and under-treatment… and yet, here we are. I mean, seriously-why is this still controversial? 🤔 It’s not rocket science. Pain first. Wait 48. If it’s not better? Antibiotics. Simple. So why does it feel like we’re arguing about climate change?

Art Gar

It is imperative to emphasize that the clinical guidelines promulgated by the American Academy of Pediatrics are predicated upon robust, peer-reviewed epidemiological evidence. The notion that parental fatigue should influence therapeutic decision-making constitutes a fundamental erosion of evidence-based medicine. To permit subjective emotional states to supersede objective clinical criteria is not merely unwise-it is ethically indefensible.

Edith Brederode

My son had the worst ear infection last winter-cried nonstop, couldn’t sleep. We gave ibuprofen, warm compress, waited 48 hours… and he bounced back! No antibiotics, no drama. 🥹 Thank you for this post-it helped me trust my gut. Also, PCV15 was a game-changer for our family! 💕

Arlene Mathison

STOP waiting. If your kid is screaming and feverish, give the antibiotics. I’ve seen kids go from ‘mild earache’ to ‘emergency surgery’ in 24 hours. Your patience doesn’t save the system-it just risks your child. Don’t be a hero. Give the meds. Save the debate for when your kid isn’t in pain.

Emily Leigh

So… we’re told to wait… but if we wait and something goes wrong… it’s on us. But if we give antibiotics and the kid gets diarrhea? That’s just ‘side effects.’ Hmm. So the system says ‘you’re responsible for outcomes’… but doesn’t give us the tools to be right? That’s not medicine. That’s a moral trap wrapped in a clinical guideline. 🤷♀️

thomas wall

It is lamentable that the public discourse on otitis media has devolved into a contest of anecdote over evidence. The data is unequivocal: watchful waiting reduces antibiotic resistance and is clinically safe in the majority of cases. To equate parental anxiety with medical necessity is to misunderstand both the nature of disease and the ethics of care. One must not confuse compassion with capitulation.