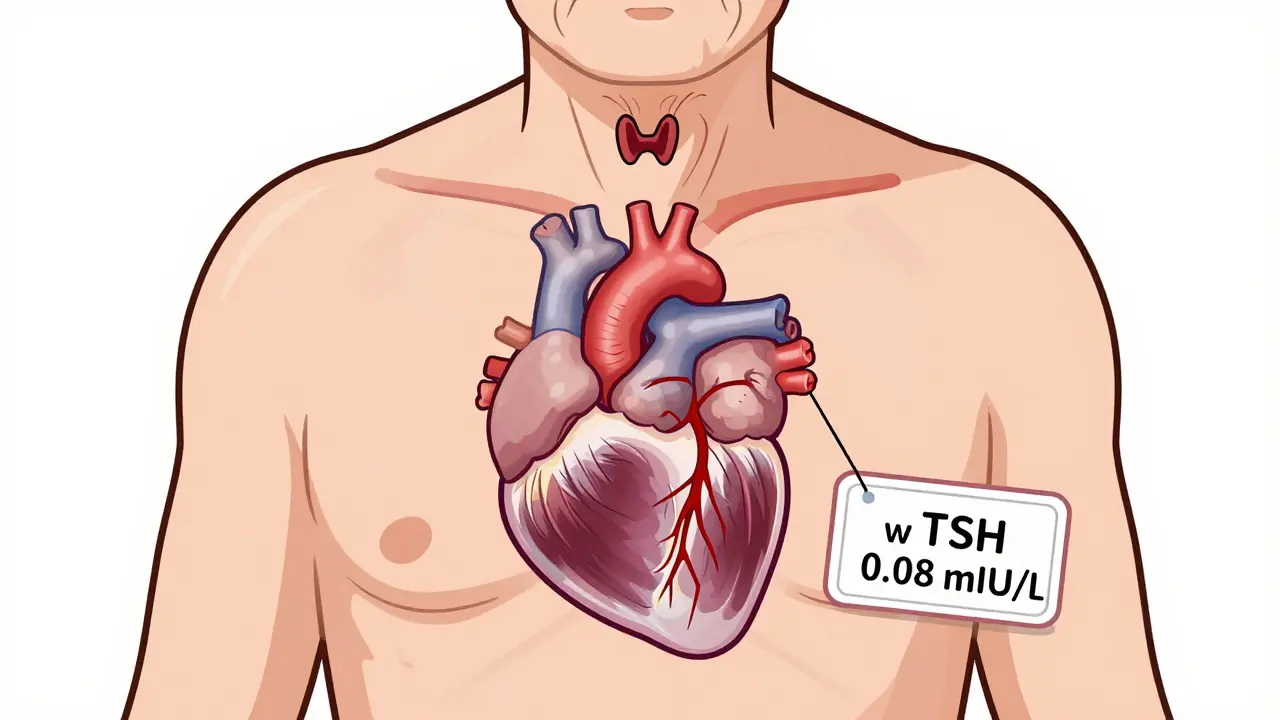

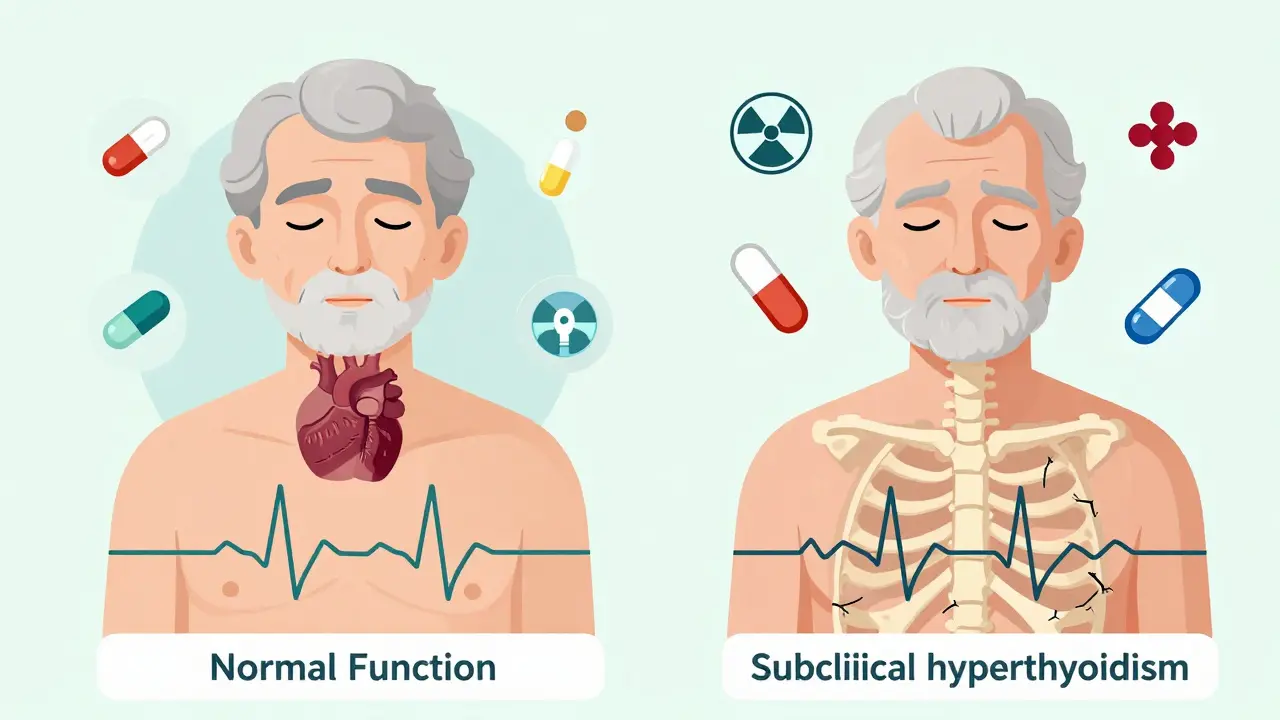

Most people don’t know they have subclinical hyperthyroidism until it shows up on a routine blood test. No shaky hands. No weight loss. No sudden heat intolerance. Just a low TSH number - and everything else normal. But that one number can tell a dangerous story, especially for older adults. Subclinical hyperthyroidism isn’t just a lab quirk. It’s a silent stress test for your heart, and ignoring it can cost you more than you think.

What Exactly Is Subclinical Hyperthyroidism?

It’s when your thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is below 0.45 mIU/L, but your free T4 and free T3 levels stay in the normal range. That means your pituitary gland is telling your thyroid to slow down - because it senses too much thyroid hormone already. But your body hasn’t crossed the line into full-blown hyperthyroidism yet. This isn’t rare. Around 4-8% of adults have it. For those over 75, the rate jumps to nearly 1 in 6. It’s most often caused by nodules in the thyroid (toxic nodular goiter) or too much thyroid medication in people being treated for hypothyroidism.

Because there are no obvious symptoms, it’s usually found by accident. A blood test for something else - maybe cholesterol or a yearly checkup - shows the low TSH. That’s why screening matters, especially after age 60. The American Thyroid Association recommends checking TSH at least once a year in older adults, particularly if they have a history of thyroid nodules or are on thyroid hormone replacement.

Why Your Heart Is the First to Feel the Strain

Even mild thyroid hormone excess doesn’t just affect metabolism. It hits your heart like a constant caffeine rush. Studies tracking over 25,000 people for 10 years found that those with TSH below 0.1 mIU/L had almost double the risk of heart failure compared to people with normal thyroid function. For atrial fibrillation - that irregular, often dangerous heart rhythm - the risk is even higher. People with TSH under 0.1 had more than twice the chance of developing AFib. Even those with TSH between 0.1 and 0.44 had a 63% increased risk.

It’s not just rhythm problems. The heart muscle thickens. The left ventricle gets heavier. Diastolic function - how well the heart relaxes between beats - worsens. Heart rate variability drops, meaning your autonomic nervous system loses its balance. Sympathetic tone (the “fight or flight” side) ramps up. Vagal tone (the “rest and digest” side) fades. That’s a recipe for arrhythmias, high blood pressure, and eventually, heart failure.

One 2012 study of 71 people with subclinical hyperthyroidism found they were nearly three times more likely to develop heart failure than those with normal thyroid levels. For those with TSH below 0.1, the risk jumped to nearly five times higher. These aren’t theoretical risks. They’re backed by large, long-term studies from the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Cardiovascular Research, and the American Family Physician journal.

Bones, Brain, and Beyond

The heart isn’t the only organ at risk. Subclinical hyperthyroidism weakens bones. When TSH drops below 0.1, fracture risk increases by more than double. This is especially dangerous for postmenopausal women and older men who already have lower bone density. The thyroid hormone accelerates bone turnover - breaking down bone faster than it can rebuild.

Cognitive effects are subtler but still real. A 2016 study in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society found that elderly patients with persistent low TSH had slower processing speed and weaker executive function - things like planning, focus, and decision-making. It’s not dementia, but it’s enough to affect daily life: forgetting appointments, struggling with bills, missing medication doses.

Quality of life usually stays okay in mild cases. But once heart symptoms kick in - palpitations, shortness of breath, fatigue - people start feeling it. And that’s when the real burden begins.

When to Treat - The Guidelines Aren’t One-Size-Fits-All

Here’s where things get messy. Not everyone with low TSH needs treatment. The American Thyroid Association doesn’t push for universal therapy. Instead, they say: look at the numbers, the age, and the risks.

- If your TSH is below 0.1 mIU/L - and you’re over 65, have heart disease, osteoporosis, or atrial fibrillation - treatment is strongly recommended.

- If your TSH is between 0.1 and 0.44 mIU/L - treat only if you have symptoms, heart changes, or bone loss.

For people on thyroid medication (like levothyroxine), the fix is simple: reduce the dose. But if the cause is a toxic nodule or Graves’ disease, it’s more complex. Radioactive iodine therapy can shut down overactive tissue. Surgery is an option for large nodules or when iodine isn’t safe. Beta-blockers like propranolol or atenolol are often used short-term to control heart rate and reduce palpitations - even if you don’t treat the root cause. They don’t fix the thyroid, but they protect the heart while you decide.

There’s no rush to treat everyone. But waiting too long can be risky. A 2015 review in Endocrine Practice warned that overtreatment - pushing someone into hypothyroidism - brings its own dangers. Hypothyroidism can raise cholesterol, worsen heart disease, and cause fatigue. So treatment isn’t about chasing a perfect TSH. It’s about balancing risks.

What Experts Are Saying

Dr. Anne R. Cappola, a thyroid researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, argues that if your TSH is below 0.1, you should be treated - even if you feel fine. “The heart doesn’t wait for symptoms,” she says. “By the time you feel it, the damage may already be done.”

Others, like Dr. Kenneth D. Burman, urge caution. “We’ve made people hypothyroid trying to fix subclinical hyperthyroidism,” he points out. “That’s not progress. It’s trading one problem for another.”

The European Thyroid Association takes a firmer stance: treat all patients with TSH under 0.1. The American guidelines are more conservative. That’s because U.S. data shows not every person with low TSH will develop complications. But in older adults - especially those with existing heart disease - the stakes are too high to ignore.

Monitoring: The Key to Safe Management

If you’re not treated right away, monitoring is non-negotiable. Here’s what works:

- TSH below 0.1: Check every 3-6 months. Watch for rising heart rate, new palpitations, or weight loss.

- TSH between 0.1 and 0.44: Annual checks are enough if you’re under 65 and have no heart or bone issues.

- Over 65 or with heart disease: Even if TSH is 0.2, get checked every 6 months.

Don’t just rely on TSH. Get an ECG to check for atrial fibrillation. Consider a bone density scan (DEXA) if you’re over 60 and have low TSH. An echocardiogram can show if your heart muscle is thickening.

And if you’re on thyroid medication? Keep a log. Note any changes in energy, sleep, or heart rhythm. Bring it to your doctor. Small dose changes can make a big difference.

What’s Coming Next

Research is catching up. The DEPOSIT study - tracking 5,000 older adults across Europe - is set to finish in 2026. It might finally answer whether treating mild cases actually prevents heart attacks and strokes. The THAMES trial in the U.S. is looking at whether treating TSH below 0.1 improves long-term heart outcomes. These studies could change guidelines overnight.

For now, the message is clear: low TSH isn’t harmless. In older adults, especially those with heart disease or bone loss, it’s a red flag. You don’t need to panic. But you do need to act - with your doctor, using data, not guesswork.

What You Can Do Today

- If you’re over 60 and have a low TSH - even if you feel fine - ask your doctor about heart and bone screening.

- If you’re on thyroid medication, don’t assume your dose is perfect. Ask if it’s still right for you.

- Track symptoms: palpitations, unexplained fatigue, trouble sleeping, or sudden weight loss.

- Don’t self-treat. Don’t stop or change your meds without medical advice.

Subclinical hyperthyroidism isn’t an emergency. But it’s a warning sign that deserves attention. Your heart won’t tell you it’s in trouble until it’s too late. But your blood test already did.

Can subclinical hyperthyroidism go away on its own?

Yes, in some cases - especially if it’s caused by temporary inflammation (like thyroiditis) or a fluctuating nodule. But if it’s due to a toxic nodule or long-term medication overuse, it rarely resolves without intervention. Persistent low TSH for more than 3-6 months usually means it’s not going away on its own.

Do I need to avoid iodine if I have subclinical hyperthyroidism?

Not necessarily. Dietary iodine (from seafood, dairy, iodized salt) doesn’t usually worsen subclinical hyperthyroidism caused by nodules or medication. But avoid iodine supplements, kelp, or contrast dyes used in imaging unless approved by your doctor. Too much iodine can trigger thyroid hormone spikes in people with nodules.

Can beta-blockers cure subclinical hyperthyroidism?

No. Beta-blockers only manage symptoms like fast heart rate and tremors. They don’t lower thyroid hormone levels or fix the root cause. They’re a bridge - not a cure. Treatment of the underlying issue (like reducing medication or using radioactive iodine) is still needed if your TSH is very low.

Is subclinical hyperthyroidism more dangerous for women or men?

Women are more likely to develop subclinical hyperthyroidism, especially after menopause, due to higher rates of autoimmune thyroid disease and nodules. But men with the condition face higher risks of heart failure and atrial fibrillation. Age and existing heart disease matter more than gender - but older men with low TSH should be monitored closely.

Should I get tested for subclinical hyperthyroidism if I’m under 50?

Routine screening isn’t recommended for people under 50 without symptoms or risk factors. But if you have a family history of thyroid disease, unexplained heart rhythm issues, or are on thyroid medication, testing is wise. Most cases under 50 are caused by Graves’ disease, which usually progresses to overt hyperthyroidism - so early detection helps.