When a drug comes in a single pill with two active ingredients - like a blood pressure medicine that combines an ACE inhibitor and a diuretic - it’s called a fixed-dose combination (FDC). These aren’t just convenient. They’re critical for millions of patients managing chronic conditions like HIV, diabetes, or asthma. But getting a generic version of these drugs to market isn’t as simple as copying a single-ingredient pill. The science behind proving they work the same way as the brand-name version - called bioequivalence - gets messy, expensive, and sometimes downright frustrating for developers. And that’s why so few generic versions of combination products ever make it to pharmacies.

Why Bioequivalence for Combination Products Is So Hard

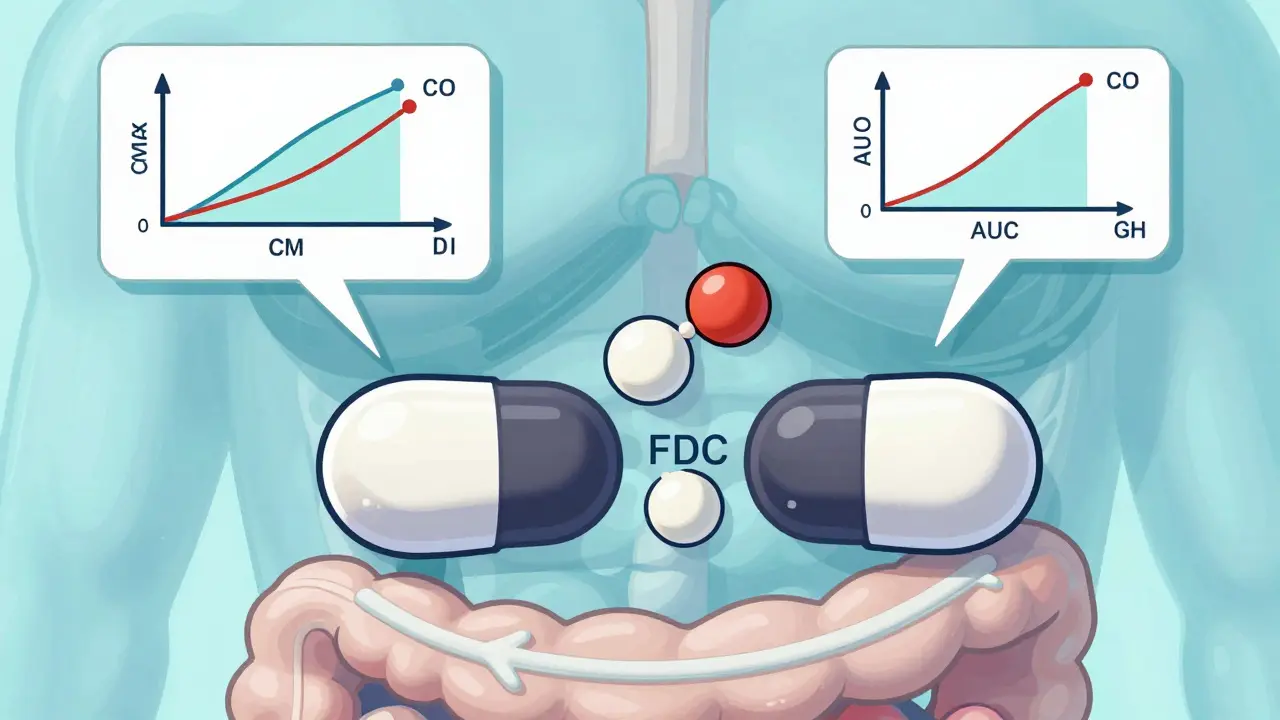

For a regular oral tablet, bioequivalence testing is straightforward. You give 24 healthy volunteers the brand-name drug and then the generic, measure how much of the active ingredient enters their bloodstream over time, and check if the peak concentration (Cmax) and total exposure (AUC) fall within 80-125% of the original. Simple. Clean. Proven. But when you have two or more drugs in one pill, things change. Each ingredient can affect how the other is absorbed, metabolized, or cleared. One might slow down the other’s release. One might bind to the other in the gut, making it less available. These interactions are unpredictable. And regulators now require generic makers to prove bioequivalence not just to the combination product itself, but also to each individual component when taken separately. That means three different reference products to compare against - not one. A 2023 FDA report found that 35-40% of initial applications for modified-release FDCs fail because they can’t meet these overlapping requirements. It’s not that the generic is unsafe. It’s that the data doesn’t line up cleanly enough.Topical Products: Measuring What You Can’t See

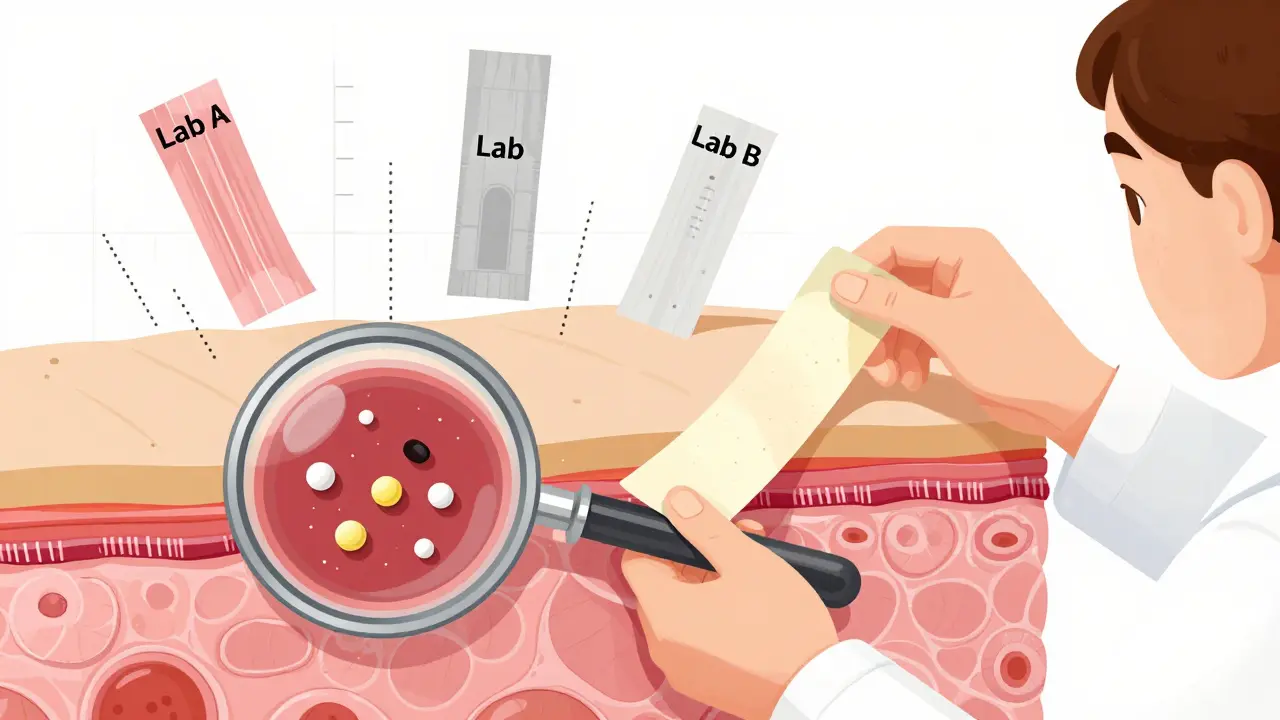

Skin creams, ointments, and foams are another nightmare. These products don’t just need to deliver the right amount of drug - they need to deliver it to the right layer of skin. For eczema or psoriasis treatments, the drug must reach the stratum corneum, the top layer of skin, to work. But how do you measure that? The FDA says to use tape-stripping: peel off 15-20 thin layers of skin with adhesive tape and test each for drug content. Sounds simple, right? It’s not. There’s no standard on how thick each strip should be, how much pressure to use, or how to account for natural skin variation between people. One lab’s tape strip might be 20% thicker than another’s, and suddenly your data looks wrong - even if the product works perfectly. A 2024 study in Frontiers in Pharmacology showed that even with perfect technique, tape-stripping only predicts in vivo performance about 70-80% of the time. That’s not good enough for regulators. Many generic developers end up doing full clinical trials with hundreds of patients - costing $5-10 million and taking years. Most can’t afford it.Drug-Device Combos: It’s Not Just the Drug

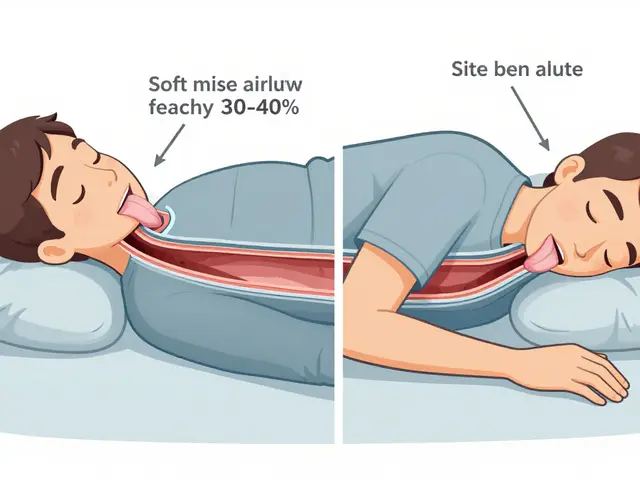

Inhalers, auto-injectors, and nasal sprays are drug-device combination products. The device matters as much as the drug. A generic inhaler might contain the exact same medicine, but if the button feels stiffer, the spray pattern is slightly different, or the mouthpiece is narrower, patients might not inhale deeply enough. The result? Less drug reaches the lungs. The FDA requires generic inhalers to match the brand in aerosol particle size distribution - specifically, within 80-120% of the original. But measuring that requires expensive equipment and controlled environments. Even small differences in propellant pressure or valve design can throw off the entire delivery profile. According to Dr. William Doub of the FDA’s Division of Complex Drug Products, 65% of complete response letters for generic inhalers cite problems with user interface testing. That’s not a drug issue. It’s a design issue. And generic companies often don’t have the engineering expertise to fix it.

Costs and Timelines That Break Companies

Developing a generic version of a simple tablet might cost $5-10 million and take 2-3 years. For a combination product? $15-25 million and 4-6 years. Bioequivalence studies alone can eat up 30-40% of that budget. Teva Pharmaceuticals reported in 2023 that 42% of their complex product failures were due to bioequivalence issues. Mylan (now Viatris) saw development timelines for topical FDCs stretch by 18-24 months. One generic version of a calcipotriene/betamethasone foam failed three times in a row because the drug penetration measurements kept varying between trials. Small and mid-sized companies are hit hardest. They don’t have the in-house labs, the analytical teams, or the regulatory consultants to navigate this. Many just give up. The result? Only 19% of the 312 complex products on the FDA’s list as of June 2024 have generic versions available.What’s Being Done to Fix It

There’s hope - but it’s slow. The FDA launched its Complex Generic Products Initiative in 2018 and has since created 12 product-specific bioequivalence guidances. These are detailed roadmaps for how to test specific combinations - like HIV drugs or asthma inhalers - instead of forcing everyone to guess. In 2024, they released 15 new draft recommendations, including one for dolutegravir/lamivudine, requiring simultaneous bioequivalence for both drugs with tighter limits. One breakthrough is the use of physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling. Instead of running 50-person clinical trials, companies can simulate how the drug behaves in the body using computer models. As of Q2 2024, 17 ANDAs for complex products were approved using PBPK models. One case from Simulations Plus showed a 40% reduction in clinical study size - saving millions. The FDA is also working with NIST to create reference standards - like certified samples of inhaler aerosols or skin penetration profiles - so labs can calibrate their equipment the same way. That’s huge. Right now, two labs testing the same product might get different results just because their machines aren’t aligned.

The Bigger Picture: Who Loses?

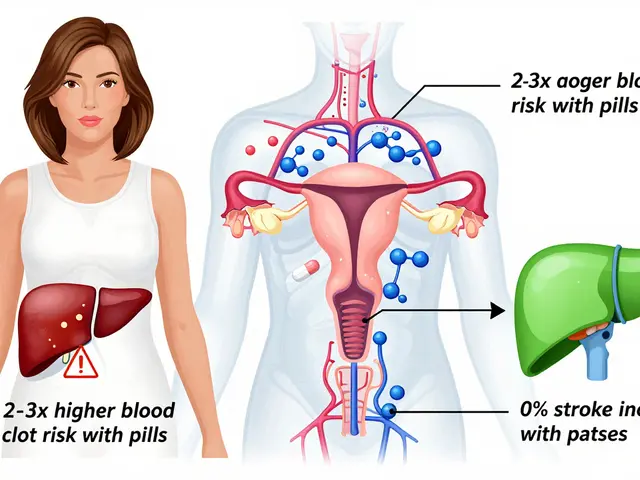

When generic versions of combination products don’t reach the market, patients pay more. Insurers pay more. Healthcare systems pay more. In 2020, generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system $373 billion. But that savings mostly came from single-ingredient pills. Complex products - which make up 38% of the global generic market - are the next frontier. If we don’t solve bioequivalence testing, $78 billion in sales of these drugs could remain locked behind brand-name prices through 2028, according to Evaluate Pharma. And it’s not just about money. Patients on HIV regimens, COPD inhalers, or psoriasis creams need affordable, reliable options. Without generics, adherence drops. Complications rise. Hospitalizations increase.What’s Next

The FDA’s Bioequivalence Modernization Initiative aims to publish 50 new product-specific guidances by 2027. That’s a start. But it’s not enough. The system still relies too heavily on clinical trials when better tools exist. Regulatory agencies need to accept more in vitro data, standardize measurement techniques, and give developers clearer feedback earlier. For now, the message is clear: if you’re developing a generic version of a combination product, don’t assume it’s like any other generic. The rules are different. The risks are higher. And the cost? It’s not just financial - it’s measured in delayed access to care.What is bioequivalence for combination products?

Bioequivalence for combination products means proving that a generic version delivers the same amount of each active ingredient, at the same rate, as the brand-name product - and that the combination behaves the same way in the body. For fixed-dose combinations, this includes showing equivalence to both the combined product and each individual component taken alone.

Why are bioequivalence studies for combination products more expensive?

They require larger sample sizes, more complex study designs, specialized equipment, and often multiple reference products to compare against. Topical and drug-device products may need clinical trials with hundreds of patients instead of healthy volunteers, pushing costs from $1-2 million to $5-10 million per study.

What’s the biggest hurdle for generic inhalers?

The biggest hurdle is matching the device’s user interface - how the patient inhales, how the spray is delivered, and how the aerosol particles are sized. Even small differences in valve design or propellant pressure can lead to lower drug delivery, and 65% of FDA rejection letters for inhalers cite this issue.

Can computer modeling replace clinical trials for combination products?

Yes, in some cases. Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling has been accepted in 17 approved generic applications as of mid-2024. It can reduce clinical trial size by 30-50% by predicting how drugs behave in the body based on chemical properties and physiology - but it still needs validation with real-world data.

Why are there so few generic versions of combination products?

Because the testing is so complex, expensive, and uncertain. Of the 312 complex products on the FDA’s list as of June 2024, only about 19% have generic versions. Many companies, especially smaller ones, can’t afford the $15-25 million investment or the 4-6 year timeline.

How does this affect patients?

Patients pay more for brand-name combination drugs, which can lead to skipped doses or treatment abandonment. For chronic conditions like HIV or asthma, this increases the risk of complications, hospitalizations, and long-term damage. Without affordable generics, access to life-saving therapies remains limited.

9 Comments

Darren McGuff

Man, I remember trying to get a generic version of that asthma combo inhaler last year. The lab data looked perfect, but the FDA came back saying the spray pattern was off by 7%. Seven percent! That’s less than the width of a human hair. We spent $2M just re-engineering the valve. And for what? So some kid in Ohio can save $15 a month? The system’s broken.

And don’t even get me started on tape-stripping. I’ve seen labs use duct tape and call it ‘standardized.’ It’s a joke.

PBPK modeling is the future. We used it for our HIV combo last quarter. Cut our clinical trials from 60 patients to 18. FDA approved it in 8 months. If they’d let us use this for everything, generics would be everywhere.

But nope. Still making us do human trials like it’s 1998.

Ashley Kronenwetter

While the challenges outlined in this post are indeed significant, it is imperative that regulatory standards remain rigorous to ensure patient safety. Compromising bioequivalence thresholds under the guise of cost reduction could lead to unintended clinical consequences, particularly for narrow-therapeutic-index medications. The current framework, though cumbersome, exists to prevent harm.

Investment in standardized reference materials and harmonized methodologies is preferable to lowering scientific benchmarks. The FDA’s approach, while slow, is deliberate-and for good reason.

Aron Veldhuizen

Let’s be honest: this isn’t about science. It’s about corporate protectionism dressed up as regulatory rigor.

The FDA doesn’t want generics because Big Pharma pays them in ghostwriters, conference sponsorships, and revolving-door jobs. That 65% inhaler rejection rate? That’s not ‘user interface issues’-that’s a manufactured barrier.

And PBPK modeling? It’s been validated in the EU for years. Why are we still doing tape-stripping like we’re in a 1970s dermatology textbook? Because if you make it easy to copy drugs, the $12,000-a-pill brand-name products lose their monopoly.

Patients aren’t the problem. Profit margins are.

Also, ‘tape-stripping’ sounds like a bad sci-fi movie. What’s next? Bloodletting with a Q-tip?

Micheal Murdoch

There’s a deeper truth here that nobody’s talking about: we treat drug development like it’s a math problem, when it’s actually a biological symphony.

Every person’s gut, skin, lungs, and metabolism are different. We’re trying to force a single, rigid standard onto something inherently variable. That’s why tape-stripping fails 20-30% of the time-it’s not the product, it’s the measurement.

What if instead of demanding perfection, we focused on *clinical equivalence*? If a generic inhaler helps 95% of patients breathe just as well as the brand, why do we care if the aerosol particle size is 82% instead of 85%?

We’re not just over-engineering tests-we’re over-engineering distrust. And the cost isn’t just financial. It’s the lives delayed because someone couldn’t afford the brand.

Let’s stop trying to measure the invisible and start measuring outcomes. Real ones. Like hospitalizations. Adherence rates. Quality of life.

That’s the science that matters.

And yes, PBPK modeling is the way forward. But it needs to be paired with real-world data, not replace it. We need both. Not one at the expense of the other.

Jeffrey Hu

You guys are missing the point. The real issue isn’t the testing-it’s the lack of qualified CROs. Most generic companies outsource to labs that have never handled a drug-device combo before. I’ve seen a lab use a non-calibrated laser diffraction system for inhaler particle sizing. The data was garbage.

Also, PBPK isn’t magic. It’s only as good as the input parameters. If your absorption constants are based on a 2010 study from a population that doesn’t reflect real-world demographics, your model is a fantasy.

And yes, I’ve reviewed 47 ANDAs for combination products. 80% of the failures were due to poor study design, not impossible regulations. Stop blaming the FDA. Start hiring better scientists.

Drew Pearlman

I just want to say-this is one of the most important conversations we’re not having.

Think about it: a diabetic patient on a combo pill can’t afford their meds, so they skip doses. Then they end up in the ER. Then they get a kidney transplant. That costs $100K. The generic pill? $30 a month.

We’re spending billions on emergency care because we’re too stubborn to fix a simple problem.

I’m not a scientist. I’m a dad whose sister can’t afford her asthma inhaler. But I know this: if we can land a rover on Mars, we can figure out how to measure a skin cream’s penetration.

Let’s stop treating patients like a cost center and start treating them like people.

And hey-if you’re reading this and work at a pharma company? Please, just make the generic. The world needs it.

Matthew Maxwell

This entire post reads like a lobbying pamphlet disguised as journalism. The fact that you frame regulatory hurdles as ‘barriers’ rather than safeguards reveals a dangerous disregard for patient safety.

Let me be clear: if a generic product doesn’t meet the exact bioequivalence standards, it is not equivalent. Period.

Patients are not guinea pigs. We do not lower standards because the math is inconvenient. The FDA’s caution is not bureaucracy-it’s bioethics.

And for the love of science, stop romanticizing PBPK modeling. It’s a tool, not a replacement for clinical evidence. The moment we allow simulation to override real-world data, we open the door to another Vioxx.

Save the activism for your Twitter feed. Medicine demands rigor, not rhetoric.

Lindsey Wellmann

Okay but like… WHY is this even a thing?? 🤯

Imagine if we did this with iPhones. ‘Oh, you want a cheaper version? Cool. But first, we need to test if your finger swipe is 85% as accurate as the original. And also, we need to measure how the screen reflects light in a controlled room with 3 different lighting conditions and 50 volunteers with slightly different skin tones. Also, here’s a tape-stripper.’

WHY IS DRUGS SO HARD?? 😭

Also, I just found out my cousin’s kid has asthma and they’re paying $800 for an inhaler. I’m crying. 💔

Someone fix this. I’ll send you cookies. 🍪

Ian Long

Look, I get why the FDA is cautious. But I also get why small companies are quitting.

There’s a middle ground. We don’t need to throw out the rules-we need to modernize them.

Let’s make PBPK the default unless there’s a proven reason to require clinical trials. Let’s fund NIST to build those reference standards. Let’s create a fast-track for products that have already been proven safe in other countries.

This isn’t about being ‘soft’ on regulation. It’s about being smart.

And if we don’t fix this, the next time a patient dies because they couldn’t afford their combo med, don’t act surprised.

We knew. We just didn’t do anything.

Let’s change that.