Boxed Warning Timeline Calculator

Understand the Boxed Warning Timeline

The FDA's boxed warnings (black box warnings) are the strongest safety alerts on prescription drug labels. Based on historical data, it typically takes 11 years on average from drug approval to the first boxed warning.

When Will This Drug Get a Boxed Warning?

When a drug gets a boxed warning, it’s not just a footnote. It’s the FDA’s loudest alarm bell. You’ll find it at the very top of a prescription drug’s prescribing information, surrounded by a thick black border, written in bold uppercase letters, and laid out in bullet points. It’s designed so no doctor, pharmacist, or patient can miss it. This isn’t about mild side effects. It’s about risks that can kill - sudden heart failure, suicidal behavior, liver failure, tendon rupture, or addiction that destroys lives. And these warnings don’t stay the same. They change. Sometimes they get stronger. Sometimes they’re removed. Tracking those changes isn’t optional - it’s life-or-death work.

What Exactly Is a Boxed Warning?

A boxed warning, also called a black box warning, is the strongest safety alert the FDA can require on a prescription drug label. It’s not a suggestion. It’s a legal requirement under 21 CFR 201.57(e). The warning must appear at the beginning of the Prescribing Information section - before contraindications, before precautions - so it’s the first thing a prescriber sees. The format is strict: bold header, bullet points, black border. No exceptions. This isn’t marketing. It’s a signal that the FDA has seen enough real-world harm to say: use this drug with extreme caution, or not at all, in certain situations.

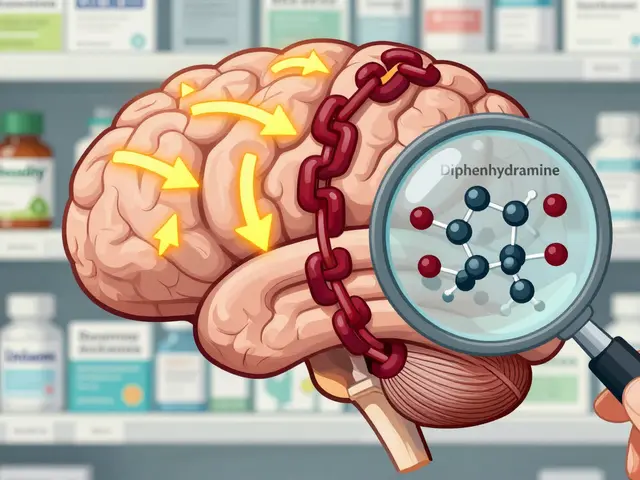

Since 1979, when the FDA first rolled out this format, these warnings have become a cornerstone of post-market drug safety. They’re not added during clinical trials. They’re added after thousands - sometimes millions - of people have taken the drug. That’s why the median time between a drug’s approval and its first boxed warning is now 11 years. That’s more than a decade of patients being exposed to a risk that wasn’t fully understood until it was too late for some.

How Often Do Boxed Warnings Change?

They change more than you think. Between 2008 and 2015, the FDA issued 111 boxed warnings. Nearly a third were brand new. Another third were major updates - adding new populations at risk, new monitoring requirements, or stronger language. The rest were minor tweaks. But here’s what matters: the most common reason? Drug addiction. That’s not a side effect. It’s a societal crisis. Other top concerns? Death (51% of new warnings) and cardiovascular risks (27%).

And it’s not just about adding warnings. They get removed too. Chantix (varenicline), a smoking cessation drug, got a boxed warning for suicidal thoughts in 2009. By 2016, after more data came in, the FDA removed it. Prescriptions dropped by 40% during the warning - and rebounded after it was gone. That’s the double-edged sword: a warning can save lives, but it can also stop people from using a drug that could help them.

The FDA’s Tracking System: SrLC Database

If you want to track these changes, there’s one place to go: the FDA’s Drug Safety-related Labeling Changes (SrLC) database. Launched in January 2016, it’s the only centralized, searchable source for all boxed warning updates since then. Before that? You had to dig through MedWatch archives, Drugs@FDA, and scattered FDA letters. Now, you can search by drug name, active ingredient, or even the exact section of the label - BOXED WARNING, CONTRAINDICATIONS, WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS.

Through December 2023, the SrLC database recorded 1,842 safety labeling changes. Of those, 147 were new boxed warnings. That’s not a small number. It’s a steady stream of updates. And it’s not just about drugs. It’s about evolving science. In March 2023, aducanumab-avwa (Aduhelm) got a new boxed warning for brain swelling and bleeding - a risk only visible in real-world use. In December 2022, fluoroquinolone antibiotics got an update to their existing warning to include persistent, long-lasting symptoms like tendon pain and nerve damage that can last for months or years.

Who’s Watching These Changes?

Healthcare providers are supposed to be on top of this. A 2017 FDA survey found that 87% of prescribers check for boxed warnings when starting a new drug. But here’s the problem: 63% admit they sometimes miss updates to existing ones. Why? Because it’s not easy. Pharmacists at academic medical centers spend 12 hours a month just tracking these changes. Hospital pharmacies use automated alerts - but 41% say those systems flood them with false positives. Community pharmacies? Only 38% have formal monitoring systems.

And it’s not just about knowing the warning exists. It’s about understanding the context. A 2020 FDA review found that 22% of recent labeling changes lacked enough clinical detail. A warning that says “risk of psychiatric events” without saying who’s at risk, how to monitor, or what to do if symptoms appear? That’s not helpful. It’s confusing. That’s why endocrinologists still argue about the Avandia warning - added in 2007 for heart risks. Many feel it was overblown and kept a useful diabetes drug off the table for years.

Who’s Affected the Most?

Not all drugs carry boxed warnings. But some classes are hit hard. Antipsychotics? 87% have them. Anticoagulants? 78%. Diabetes meds? 63%. That’s not random. These are drugs taken long-term, often by older or sicker patients. The more exposure, the more chances for rare but deadly side effects to show up. And when they do, the FDA acts - but slowly. The median 11-year lag means patients are paying the price while regulators gather evidence.

Meanwhile, the market is responding. The global pharmaceutical risk management industry grew from $1.2 billion in 2015 to $2.8 billion in 2023. Companies are investing in software, training, and compliance teams just to keep up. Specialty pharmacies that track these changes closely saw 27% fewer medication-related adverse events. Community pharmacies? Not so much. The gap is real.

The Future: Can Boxed Warnings Get Better?

The FDA knows the system is outdated. The black box was designed for paper labels. Today, most prescriptions are digital. Most patients get their info on apps and websites. The FDA’s 2023 Strategic Plan says it wants to modernize the format by 2026. Pilot tests are already underway - testing clearer language, visual icons, and even color coding to signal severity levels. The goal? Make warnings easier to understand, not just harder to ignore.

There’s also a push to cut the 11-year lag. The FDA’s partnership with OHDSI, a global health data network, is using real-world patient data from millions of electronic health records to spot dangers faster. The target? Reduce the time from risk discovery to warning to under five years. That’s ambitious. But if they pull it off, it could save thousands of lives.

Still, critics aren’t satisfied. Dr. Jerry Avorn of Harvard says we need a tiered system - not just one loud alarm for every risk. Some dangers are rare. Some are theoretical. Some are proven. A single black box doesn’t tell the difference. A better system might have red, yellow, and green alerts - letting doctors know not just that there’s a risk, but how serious it really is.

What This Means for Patients and Providers

If you’re a doctor or pharmacist, you can’t afford to ignore these updates. A single missed change could mean prescribing a drug that causes harm. Use the SrLC database. Set up alerts. Talk to your pharmacy team. Don’t rely on memory.

If you’re a patient, ask your provider: “Does this drug have a boxed warning? Has it changed since I last took it?” Don’t assume your last prescription is still safe. Medications evolve. So do their risks.

And if you’re on a drug with a boxed warning - don’t panic. These warnings exist to help you, not scare you away. But do know what you’re taking. Ask about monitoring. Ask about alternatives. Ask if the warning has been updated. Knowledge is your best defense.

What is a boxed warning on a drug label?

A boxed warning, also called a black box warning, is the strongest safety alert the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires on prescription drug labels. It highlights serious or life-threatening risks, such as death, organ failure, or addiction. It appears at the top of the prescribing information, surrounded by a black border, written in bold uppercase letters, and formatted in bullet points to ensure it’s noticed immediately.

How often does the FDA add or update boxed warnings?

Between 2008 and 2015, the FDA issued 111 boxed warnings. About 29% were new, 32% were major updates, and 40% were minor changes. Since 2016, the FDA has issued 147 new boxed warnings through December 2023. Updates happen regularly as new safety data emerges from real-world use - not just clinical trials. The median time from drug approval to a boxed warning is now 11 years.

Where can I find official updates to boxed warnings?

The FDA’s Drug Safety-related Labeling Changes (SrLC) database is the official, centralized source for all boxed warning updates since January 2016. It allows users to search by drug name, active ingredient, or label section. For changes before 2016, you need to consult MedWatch archives and Drugs@FDA. Most healthcare providers use the SrLC database as their primary tool for tracking these changes.

Can boxed warnings be removed from a drug label?

Yes. If new evidence shows a previously listed risk is not as serious as once thought, or if the benefits clearly outweigh the risks in a broader population, the FDA can remove or modify a boxed warning. For example, the boxed warning for Chantix (varenicline) regarding suicidal thoughts was removed in 2016 after further studies showed the risk was lower than initially reported.

Why do boxed warnings take so long to appear after a drug is approved?

Clinical trials involve thousands of patients, but real-world use involves millions. Rare or long-term side effects often don’t show up until the drug is used widely over years. The FDA waits for enough real-world data to confirm a pattern of harm before issuing a boxed warning. That’s why the average time from approval to warning is 11 years - it takes time to gather, analyze, and verify the evidence.

Are boxed warnings effective in changing prescribing habits?

Yes, they often do. A 2022 survey on Sermo found that 68% of physicians changed how they prescribed fluoroquinolones after the tendon rupture warning was added in 2008. A 2021 study showed that when boxed warnings were paired with Medication Guides, patient understanding of risks jumped from 42% to 78%. However, some providers feel certain warnings are overly cautious, leading to underuse of effective drugs - like Avandia for diabetes - even when the risk is low for most patients.

What Comes Next?

The boxed warning system isn’t broken - it’s just old. It was built for a world of paper labels and slow data collection. Today, we have real-time electronic health records, AI-powered surveillance, and global data networks. The FDA’s push to cut the warning lag from 11 years to under 5 is not just ambitious - it’s necessary. The next decade will see smarter, faster, and more nuanced safety alerts. But until then, every prescriber, pharmacist, and patient needs to treat each boxed warning like a live alert - not a static label. Because when a drug’s warning changes, the risk changes. And so should your action.

12 Comments

Ellen Sales

Wow. This is the kind of post that makes you stop scrolling. I’ve seen boxed warnings on scripts for years, never really thought about how they evolve-or how many lives hinge on someone catching an update. The Chantix example? That’s the exact moment I realized these aren’t just bureaucracy-they’re living documents. And the 11-year lag? That’s not patience. That’s a graveyard of unacknowledged risks.

Jennifer Griffith

frankly i think the fda is way too slow and also way too dramatic. like why does every other drug get a black box now? it’s like they’re trying to scare people away from meds so they can push supplements. i’ve seen patients ditch effective drugs because of a warning that was later removed. it’s chaos.

Kimberley Chronicle

From a pharmacovigilance standpoint, the SrLC database is a game-changer-but only if integrated into EHR workflows. Right now, it’s a siloed resource. We need automated alerts tied to clinical decision support systems, not just manual checks. The 41% false positive rate in hospital systems? That’s a design failure, not a data problem. We need risk stratification: red/yellow/green, not just black. Dr. Avorn nailed it.

Pallab Dasgupta

As someone who’s seen patients on antipsychotics for 15+ years, this hits home. I’ve watched families lose hope because a warning got added and no one told them it could be removed. The system’s broken when the only people who track this are the ones getting paid to do it. What about the single mom on Medicaid who just gets her script filled at CVS? She’s not reading FDA databases. She’s praying the pill doesn’t kill her. We need better communication-not just better data.

fiona collins

Patients need simple summaries. Not jargon. Not bullet points. Just: 'This drug can cause X. Here’s what to watch for. Here’s what to do.' That’s it.

giselle kate

They’re just trying to control us. Big Pharma pays the FDA to scare people into taking less medicine so they can sell more 'natural' stuff. The black box? It’s propaganda. Look at how many warnings were removed after public outcry. This isn’t safety-it’s control.

Emily Craig

Oh great, another 12-page essay on how we’re all doomed because the FDA doesn’t update labels fast enough. Meanwhile, my grandma took her blood thinner for 20 years without a single issue. Maybe the system works fine for most people? Not everyone needs a PhD to take a pill.

Srikanth BH

As an Indian pharmacist, I can tell you-this isn’t just an American problem. We see the same delays here. Patients get drugs with outdated labels because the system doesn’t reach rural clinics. I’ve had to manually print FDA updates and tape them to the counter. It’s ridiculous. We need mobile alerts in local languages. Not just English PDFs no one reads.

Karen Willie

I’ve worked in oncology for 18 years. Every boxed warning I’ve seen changed-either strengthened or removed-has directly affected a patient’s outcome. One woman survived metastatic breast cancer because her oncologist caught the updated warning on a drug that had been pulled from the market for cardiac risk. She didn’t know. I did. That’s why this matters. Not because it’s complex. Because it’s personal.

Leisha Haynes

Can we talk about how the FDA’s website looks like it was designed in 2003? Like, I’m not even mad-I’m just disappointed. If you want people to actually use the SrLC database, maybe make it not look like a relic from the dial-up era? Also, why is the search function so broken? I typed 'fluoroquinolone' and got 47 unrelated entries. Come on.

Shivam Goel

Let’s be real: 147 new boxed warnings since 2016? That’s not progress. That’s failure. It means the pre-market trials are garbage. If you’re not catching life-threatening risks in Phase III with 5,000 patients, you’re not doing your job. The 11-year lag isn’t ‘science’-it’s negligence. And the fact that 63% of prescribers miss updates? That’s not human error. That’s systemic collapse. We’re not managing risk-we’re managing chaos.

Andrew McAfee

As someone who’s worked in global health, I’ve seen how these warnings ripple. In Nigeria, a patient died because their doctor didn’t know the fluoroquinolone warning was updated. The FDA’s update was in English, on a website that didn’t load on their phone. We need global, multilingual, offline-accessible alerts. This isn’t just a U.S. problem. It’s a global equity issue.