When older adults leave the doctor’s office, they often walk away confused. Not because they don’t care - but because the information they’re given is too complex, too small, or too fast. Around 63% of seniors report difficulty understanding medication instructions. Half of them don’t ask for help, not because they know everything, but because they’re embarrassed. This isn’t just a communication gap - it’s a safety issue.

Why Standard Medical Materials Don’t Work for Seniors

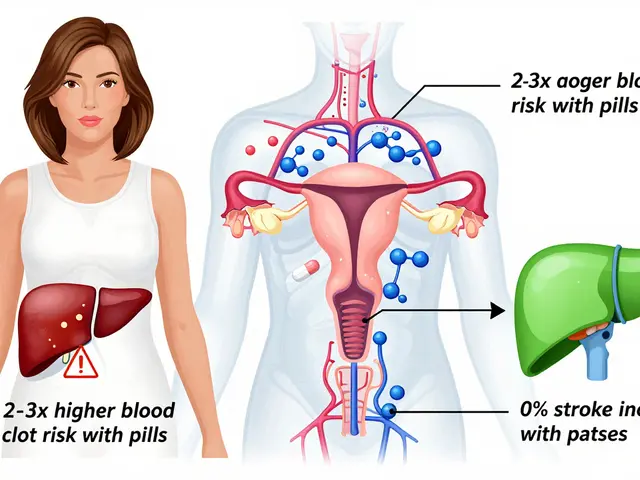

Most health brochures are written for people who read at a 7th or 8th grade level. But in the U.S., about 20% of adults - including many seniors - read at or below a 3rd grade level. That means if a pill bottle says "take once daily with food," and the person doesn’t know what "daily" means, or confuses "1 tablet" with "1 capsule," they’re already lost. Sensory changes make it worse. Vision fades. Hearing dulls. Memory slows. A 7-point font might look fine to a 30-year-old, but to someone with macular degeneration, it’s unreadable. A dense paragraph of medical jargon - "hypertensive urgency," "polypharmacy," "adherence" - doesn’t just confuse. It shuts people down. The CDC found that 71% of adults over 60 struggle with basic print materials. 80% have trouble reading forms or charts. And 68% can’t do simple math - like figuring out how many pills to take over a week. These aren’t rare cases. They’re the norm.What Makes Senior Patient Education Materials Work

Effective materials for older adults follow clear, proven rules - not guesses or trends. Here’s what actually works:- Font size: 14-point minimum - no smaller. Times New Roman or Arial are best. Avoid decorative fonts.

- High contrast - black text on white background. Avoid gray text or colored backgrounds.

- Simple language - use words like "take" instead of "administer," "medicine" instead of "pharmaceutical agent."

- One idea per page - don’t overload. A single topic like "How to take your blood pressure" fits on one page.

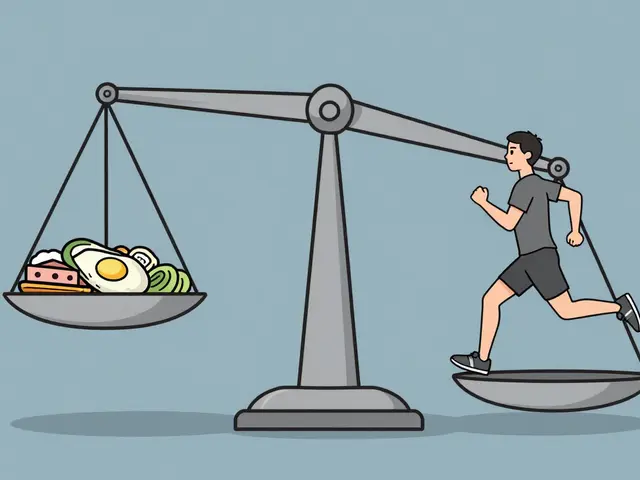

- Visuals over text - a picture of a pill organizer with arrows showing morning, noon, night is worth 100 words.

- Use real-life examples - "Like this: If you take your blood pressure pill every morning with breakfast, set your coffee maker to turn on at 7 a.m. as a reminder."

Proven Formats That Get Results

Not all formats are equal. Some work better than others for seniors.One-page fact sheets - these are the most used and most trusted. They’re easy to hold, easy to read, and easy to share with family. HealthPartners Institute has over 1,300 of these in their library, covering everything from diabetes to falls prevention.

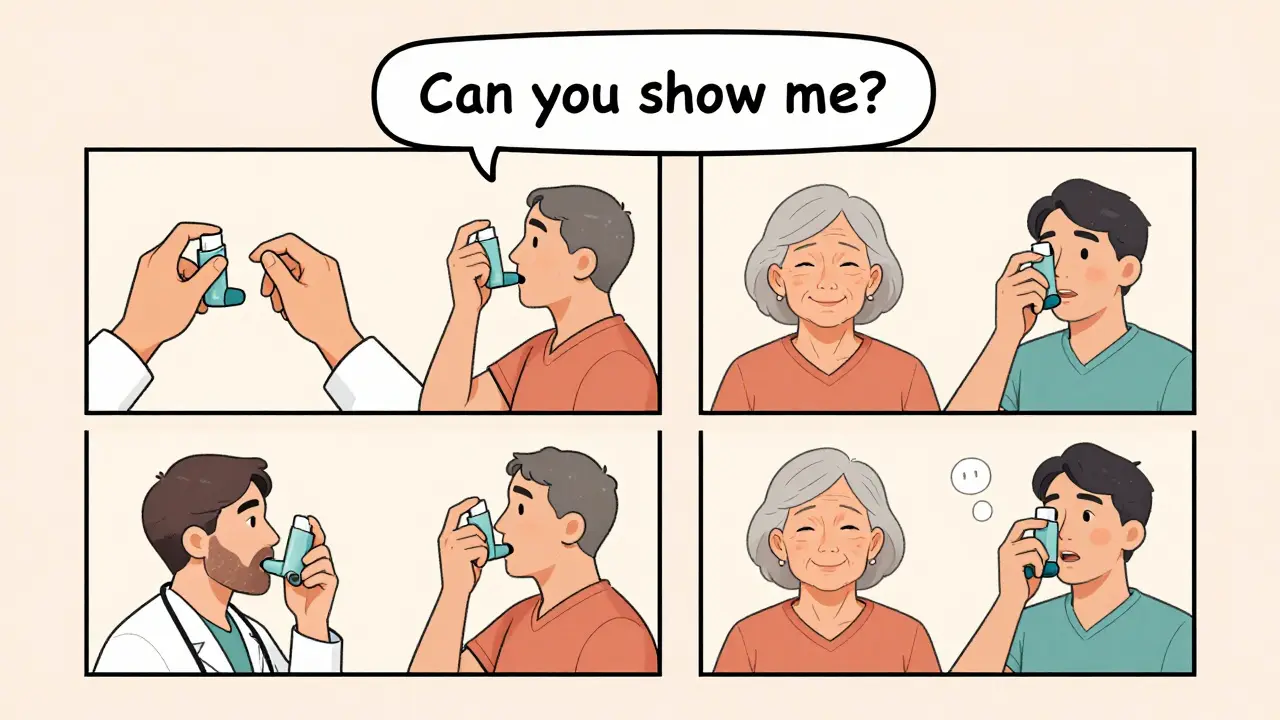

Step-by-step illustrated guides - a 2023 review of 47 studies found that illustrated instructions improved medication adherence by 37% compared to text-only. For example: a series of four drawings showing how to use an inhaler - hand position, breath in, hold, breathe out - with no words needed.

Video demonstrations - with telehealth use jumping from 17% in 2019 to 68% in 2023, video is now essential. But videos must be slow, clear, and captioned. NIA’s updated Go4Life program, released in January 2024, uses voice-over and large on-screen text so seniors can follow along even if they can’t hear well.

Teach-back method - this isn’t a fancy term. It’s simple: after explaining something, ask the patient to explain it back in their own words. "Can you show me how you’d take this pill?" If they get it right, they’re more likely to remember. Research shows this adds just 2.7 minutes to a visit but boosts understanding by 31%.

Where to Find Trusted Materials

You don’t need to create everything from scratch. There are free, reliable sources built by experts:- HealthinAging.org - run by the American Geriatrics Society. Over 2 million people use it each year. All materials are reviewed by geriatric doctors and tested with seniors.

- MedlinePlus Easy-to-Read - the National Library of Medicine’s collection includes 217 resources, alphabetized by topic. Everything is checked with the Health Education Materials Assessment Tool (HEMAT).

- National Institute on Aging (NIA) - their "Talking With Your Older Patients" guide is used by clinics nationwide. Updated in June 2023, it includes scripts for doctors and printable handouts.

- CDC Healthy Aging - their 2023 guidelines emphasize digital literacy too. Many seniors now use apps to track meds, but if they don’t know how to tap "confirm," they might miss doses.

These aren’t just websites. They’re lifelines. Amanda C., a caregiver in San Diego, said after using HealthinAging.org: "I couldn’t believe how much they made simple. I finally understood what my mom’s doctor was saying."

What Doesn’t Work - and Why

Some well-intentioned efforts miss the mark.Big PDFs - sending a 20-page PDF via email? Most seniors can’t open it. Or they print it, and the font shrinks to 8-point. Bad.

Text-heavy pamphlets - if it looks like a textbook, it gets ignored. One study showed seniors picked up a bright, colorful one-page handout 5 times more often than a gray, 6-page booklet.

Assuming they know how to use tech - just because a grandchild uses a smartphone doesn’t mean Grandma does. Only 41% of seniors over 70 feel confident using health apps. A 2023 survey found 51% didn’t ask for help with confusing instructions because they feared looking "stupid."

Don’t assume. Ask. "Do you need this in print?" "Would you like me to read it out loud?" "Can you show me how you’d use this?"

Why This Matters - The Real Impact

This isn’t about being nice. It’s about saving lives - and money.Hospitals that use proper senior patient education see 14.3% fewer readmissions among Medicare patients. That’s $1,842 saved per person - not just for the system, but for families who lose income or time caring for someone who ends up back in the hospital.

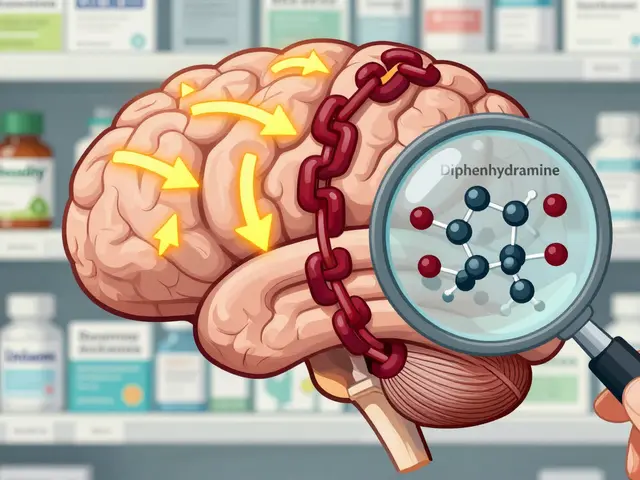

People with low health literacy are 2.3 times more likely to say their health is poor. They’re 1.7 times more likely to have diabetes. They’re more likely to have falls, infections, and bad reactions to meds.

And the cost to the whole system? Between $106 billion and $238 billion a year - mostly from preventable errors.

Yet, only 28% of U.S. healthcare systems have fully put these practices into daily use. Staff are busy. Budgets are tight. But the data doesn’t lie: when you make materials clear, people get better - faster.

How to Start - Even With Limited Resources

You don’t need a big team or a big budget to make a difference.- Swap one brochure - replace a dense handout with a one-page version from HealthinAging.org or MedlinePlus. Use the 14-point font rule.

- Add one visual - draw a simple pill schedule on a whiteboard during the visit. Use arrows. Use colors.

- Use teach-back - after explaining, say: "Just to make sure I was clear - how would you take this at home?"

- Offer options - "Would you like this in large print? Or would you like me to email it to your child?"

- Test it - if you make your own material, ask 3-5 older adults to read it. If they stumble, fix it.

It’s not about perfection. It’s about progress. Even small changes reduce confusion. And less confusion means safer, healthier seniors.

The Future Is Personal

The next big step? Personalized materials. The National Institutes of Health is funding a $4.2 million project to build AI tools that adjust content based on how a person sees, hears, and remembers. Imagine a handout that changes font size automatically - or a video that slows down if the viewer pauses too long.But until then, the best tools are simple: clear words, big print, pictures, and patience.

Seniors don’t need more information. They need better communication. And that starts with one question: "Do you understand?" - followed by, "Can you tell me how you’ll do it?"

What reading level should senior patient education materials be written at?

Senior patient education materials should be written at a 3rd to 5th grade reading level. This matches the reading ability of about 20% of U.S. adults, including many older adults. Even though the national average is higher, research shows that simplifying language to this level improves understanding by 42% in seniors compared to standard medical materials.

What font size is recommended for older adults?

The minimum recommended font size is 14-point. Many seniors have vision changes like macular degeneration or cataracts, so smaller fonts are hard to read. Use clear, sans-serif fonts like Arial or Times New Roman. Avoid italics, underlines, or decorative fonts that reduce readability.

Are videos better than printed materials for seniors?

Videos can be more effective - especially when they show step-by-step actions like using an inhaler or checking blood sugar. But they must be slow, clear, and captioned. Many seniors also prefer printed copies to keep for reference. The best approach is to offer both: a video they can watch at home and a simple one-page handout to hold onto.

Why don’t seniors ask for help when they don’t understand?

About 51% of older adults don’t ask for clarification because they feel embarrassed or fear being seen as unintelligent. Some worry they’ll bother the doctor. Others think everyone else understands and they’re the only one who’s confused. Creating a calm, non-judgmental environment - and using phrases like "Many people find this confusing" - helps reduce that fear.

Can I use plain language even if the doctor uses medical terms?

Yes - and you should. Doctors may say "hypertension," but patients hear "high blood pressure." Always translate medical terms into everyday language. Use phrases like: "This medicine is for your heart. It helps lower your blood pressure." This doesn’t mean dumbing down - it means making it real.

How can families help with senior patient education?

Family members can sit in on appointments, take notes, or ask the doctor to repeat key points. After the visit, they can help the senior use the materials - reading handouts aloud, setting pill reminders on a phone, or drawing a simple schedule. They can also check in weekly: "Did you take your pills like the picture showed?" This support cuts confusion and increases safety.

What to Do Next

Start small. Pick one patient. Pick one condition - like diabetes or high blood pressure. Find a free, easy-to-read handout from HealthinAging.org or MedlinePlus. Print it in 14-point font. Show it to the patient. Ask them to explain it back. Then do it again tomorrow with someone else.You don’t need to fix everything at once. You just need to start. Because when information is clear, people don’t just understand - they get better.

15 Comments

Josh josh

man i wish my grandpa's doctor had this 5 years ago he took his blood pressure pill with his coffee and his tea and his orange juice and ended up in the ER again

just make it simple. big letters. pictures. done.

bella nash

The imperative for linguistic simplification in geriatric health communication is not merely a matter of accessibility, but a fundamental ethical obligation within the clinical paradigm. The conflation of medical terminology with lay vernacular must be systematically institutionalized.

SWAPNIL SIDAM

In India we do this naturally. Doctor speaks slow. Family holds paper. We draw pills on notebook. No fancy words. Just show. They understand. Simple is safe.

Geoff Miskinis

Let's be honest - this is just another wellness-adjacent bandwagon. You're advocating for dumbing down medical science to appease a demographic that can't be bothered to learn basic literacy. The real issue is societal decay, not font size.

Sally Dalton

omg YES this is so true!! i helped my aunt last month and she was crying because she thought 'once daily' meant once a week?? i printed out the big font one-page thing from healthinaging.org and she cried again but this time happy 😭❤️

eric fert

I’ve been in this field for 22 years and let me tell you - most of this is common sense. But here’s the real problem: hospitals don’t train staff. They don’t pay for it. They don’t care. They’re running on fumes and Medicaid reimbursements. And now you want them to print giant posters? Good luck with that. Meanwhile, the same seniors who can’t read are being sold $1000 ‘smart pill dispensers’ that require an app login and two-factor authentication. The system is broken. And this article? It’s just a Band-Aid on a hemorrhage.

Curtis Younker

THIS RIGHT HERE IS THE FUTURE. Imagine if every clinic started with one page. One visual. One teach-back. Just one. You’d be shocked how many lives you save. I work in a small clinic in Ohio and we started doing this last year. Readmissions dropped 20%. Nurses are happier. Patients feel seen. It’s not magic. It’s just kindness with structure. Start today. One patient. One page. One change. You got this.

Shawn Raja

Ah yes, the great American myth: ‘Seniors are too dumb to understand medicine.’ Newsflash - they’re not dumb. They’re being spoken to like children by people who think ‘pharmaceutical agent’ sounds smarter than ‘pill.’ And don’t even get me started on the ‘teach-back’ method. That’s just a fancy way of saying ‘prove you’re not stupid.’ But hey, at least we can print it in 14-point font and call it justice. 🤡

Ryan W

This is why America is falling apart. We’ve turned healthcare into a daycare. If your grandfather can’t read a 7th-grade pamphlet, maybe he shouldn’t be managing his own meds. Let the family handle it. Or put him in a facility. Stop catering to functional illiteracy like it’s a civil right. We’re not babysitting.

Henry Jenkins

I’m curious - what happens when the patient has cognitive decline but still has intact vision? Or when they’re hard of hearing but can read well? The guidelines here are solid for the average senior, but what about the outliers? Is there any research on personalized adaptive materials beyond font size and contrast? I’ve seen cases where a 14-point font is useless if the patient can’t retain the sequence of steps, regardless of clarity.

TONY ADAMS

my mom used to say she didn't ask because she didn't want to waste the doctor's time. then she had a stroke because she mixed up her heart pills. now i print everything in 18 point and tape it to the fridge. she still forgets. but at least she can see it.

Napoleon Huere

There’s a deeper truth here: we treat health literacy like a personal failure, when it’s actually a systemic one. The burden is placed on the patient to decode a language designed by engineers, not humans. We’ve built a cathedral of knowledge and then blamed the poor for not knowing how to read the stained glass.

Neil Thorogood

I just printed out the inhaler guide for my dad. 4 pictures. 0 words. He looked at it, nodded, and said ‘ohhhh’ like he’d been waiting 10 years to get it. 🙌 I’m crying. This is why we do this. Not for stats. For moments like this. 💙

Robin Van Emous

I really appreciate how this article doesn’t just list fixes - it shows the human cost. I work at a senior center, and last week, a woman asked me if ‘polypharmacy’ meant ‘many pills’ or ‘a kind of medicine.’ I showed her the one-pager on meds. She hugged me. We don’t need more technology. We need more patience. And bigger fonts.

Angie Thompson

this made me wanna cry and high-five someone at the same time!! 🤗💖 my grandma thought ‘take with food’ meant she had to eat a whole sandwich every time - now she uses the picture of the apple and toast and she’s so proud. she even taught her book club about it. small wins, y’all. small wins.