digoxin has been a staple in cardiology for more than a century, but its role in modern heart‑failure management-especially diastolic heart failure-has become a hot debate.

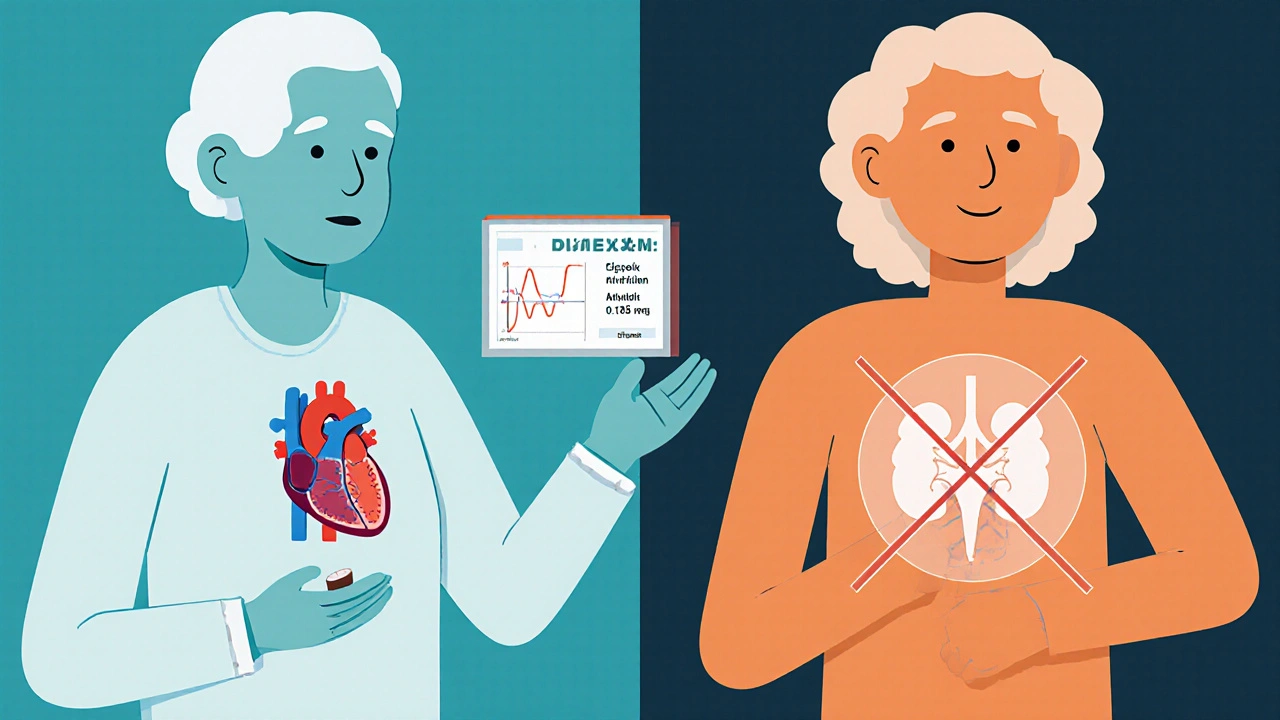

What Is Diastolic Heart Failure?

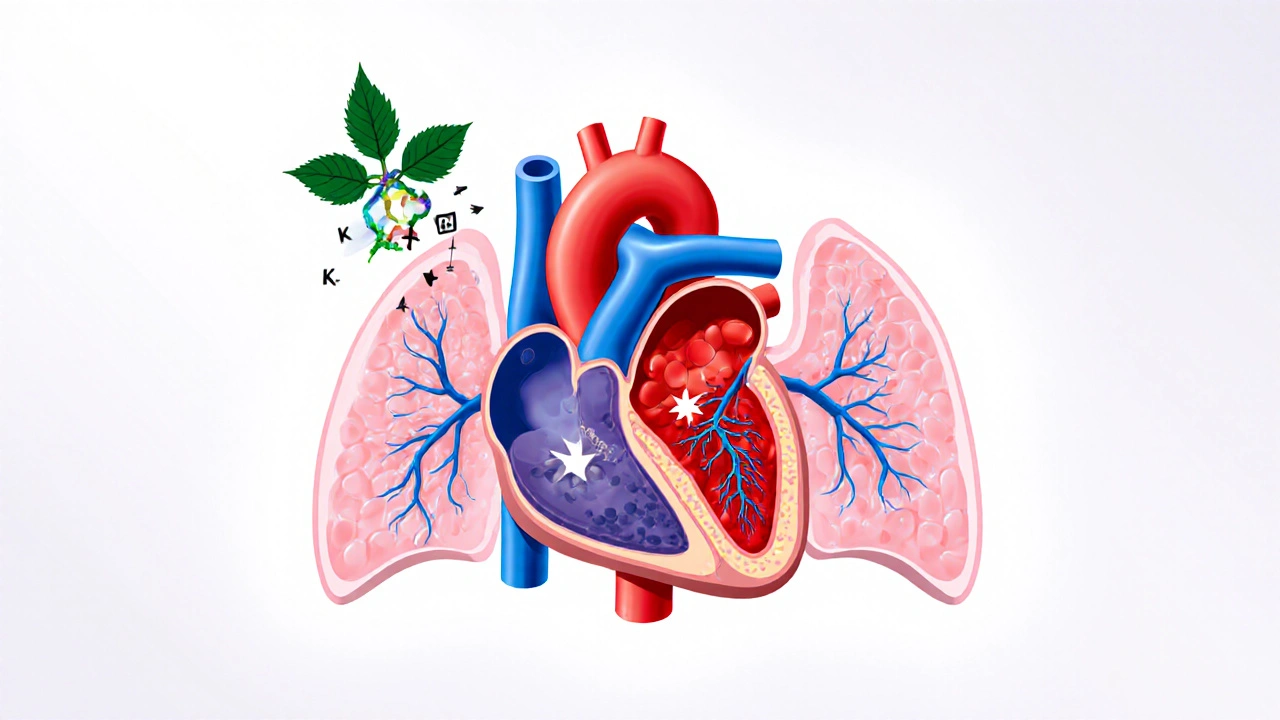

When the left ventrventricle becomes stiff and can’t relax properly, blood backs up into the lungs. This condition is known as Diastolic Heart Failure (also called heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, HFpEF). Unlike systolic failure, where the heart’s pumping ability drops, patients with diastolic failure usually maintain a normal ejection fraction (≥50%). The main symptoms-shortness of breath, fatigue, and exercise intolerance-stem from elevated filling pressures.

Why Digoxin Gets Mentioned in HFpEF Discussions

Digoxin belongs to the class of Cardiac Glycosides compounds that inhibit the Na⁺/K⁺‑ATPase pump, leading to increased intracellular calcium and stronger contractions. Its classic use is to boost contractility in systolic heart failure and to control rate in atrial fibrillation. The question is whether those same mechanisms help a stiff ventricle.

Two biological actions matter for diastolic patients:

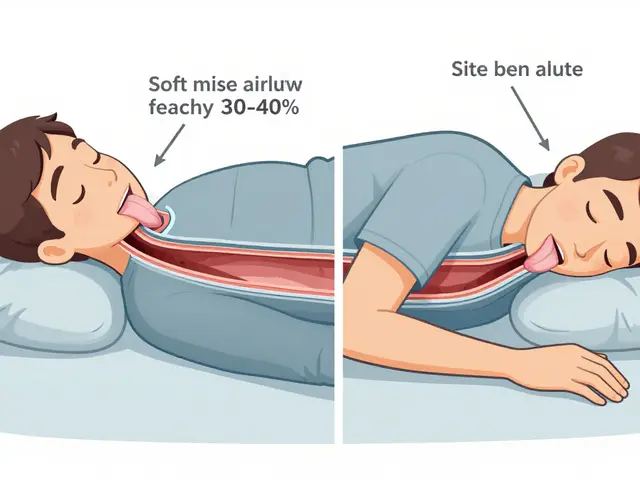

- Neurohormonal modulation: Digoxin enhances vagal tone, reducing sympathetic over‑drive, which can lower heart‑rate and improve filling time.

- Positive inotropy: Even a modest increase in contractility may improve forward output without worsening stiffness, provided the dose is low.

Key Clinical Trials and Their Take‑aways

Evidence comes mainly from subgroup analyses of larger trials that weren’t designed for HFpEF. Here’s a quick rundown:

- DIG Trial (1997‑2001): Enrolled over 7,800 patients with left‑ventricular ejection fraction ≤45%. A post‑hoc look at the ~10% who had preserved EF showed no mortality benefit but a slight reduction in hospitalization for heart‑failure symptoms.

- J‐DHF (Japan Diastolic HF) Study, 2015: Randomized 480 HFpEF patients to low‑dose digoxin (0.125 mg daily) vs placebo. After 12 months, the digoxin group had a 15% lower rate of hospital readmission, but quality‑of‑life scores (MLHFQ) were unchanged.

- EURO‑HFpEF Registry, 2022: Observational data indicated that patients already on digoxin for atrial fibrillation had a 12% lower all‑cause mortality, but the effect vanished after adjusting for comorbidities.

Bottom line: Digoxin may cut down on heart‑failure admissions, but it doesn’t clearly improve survival or symptoms in a pure HFpEF cohort.

Guideline Recommendations (2023 ESC & 2024 AHA/ACC)

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) place digoxin in a secondary role for HFpEF:

- ESC 2023: Class IIb recommendation-consider digoxin only if the patient has concurrent atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, or if recurrent hospitalizations persist despite optimal guideline‑directed therapy.

- AHA/ACC 2024: Class IIb, Level of Evidence B-use digoxin optional for symptom relief when beta‑blockers, ACE inhibitors, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists have failed to control congestion.

Both societies stress careful dosing (usually 0.125 mg daily) and close monitoring of serum levels, especially in older adults or those with renal impairment.

Practical Dosing and Monitoring

Because the therapeutic window is narrow, a low‑dose strategy is standard for HFpEF:

| Patient Characteristic | Starting Dose | Target Serum Level (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Normal renal function (eGFR ≥60 mL/min) | 0.125 mg once daily | 0.5-0.8 |

| Reduced renal function (eGFR 30‑59 mL/min) | 0.125 mg every other day | 0.5-0.8 |

| Age >75 years or frailty | 0.125 mg every other day | 0.5-0.8 |

Check serum digoxin level 7‑10 days after initiating therapy, then every 3-6 months once stable. Watch for signs of toxicity: nausea, visual disturbances (yellow‑green halos), and arrhythmias.

When Digoxin Is Probably Not Worth It

Patients without atrial fibrillation, with well‑controlled blood pressure, and who are already on beta‑blockers and ACE inhibitors rarely gain additional benefit. Also avoid digoxin if the patient has:

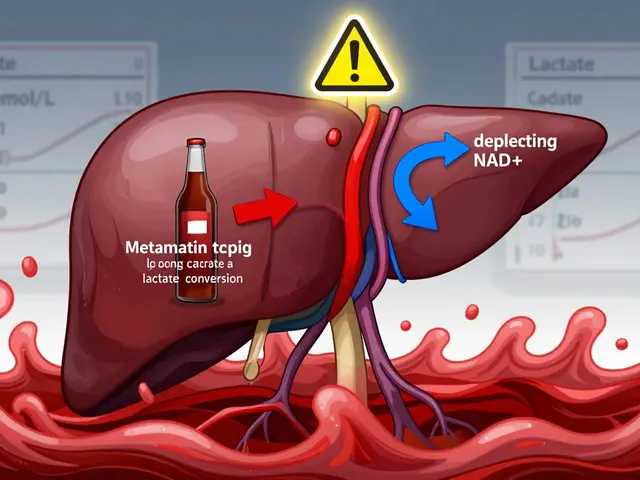

- Severe chronic kidney disease (eGFR <30 mL/min)

- Baseline hyperkalemia (K⁺ >5.5 mmol/L)

- Concomitant use of drugs that raise digoxin levels (e.g., amiodarone, quinidine, verapamil)

In such cases, the risk of arrhythmia or digitalis toxicity outweighs the modest reduction in hospital admissions.

Comparing Digoxin With Other HFpEF Therapies

Below is a quick side‑by‑side look at the most common pharmacologic options for diastolic heart failure.

| Drug Class | Primary Goal | Evidence of Mortality Benefit | Typical Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta‑Blockers | Heart‑rate control, improve filling time | Mixed; some subgroup benefits | Bradycardia, fatigue |

| ACE Inhibitors / ARBs | Afterload reduction, BP control | Limited for HFpEF | Cough, hyperkalemia |

| Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists | Reduce fibrosis, control volume | Some evidence of reduced hospitalizations | Hyperkalemia, renal decline |

| SGLT2 Inhibitors | Diuretic‑like, improve cardiac metabolism | Positive outcomes in EMPEROR‑Preserved trial (2023) | UTIs, genital mycotic infections |

| Digoxin | Neurohormonal modulation, modest inotropy | No clear mortality benefit; reduces hospital readmission in select groups | Arrhythmias, nausea, visual changes |

With the arrival of SGLT2 inhibitors showing clear morbidity benefits, many clinicians now reserve digoxin for niche scenarios.

Patient Selection Checklist

- Diagnosed HFpEF (NYHA Class II‑III, EF ≥50%).

- Concurrent atrial fibrillation with rate >80 bpm despite beta‑blocker.

- History of ≥2 heart‑failure hospitalizations in the past year.

- Renal function eGFR ≥30 mL/min and stable electrolytes.

- No interacting medications that increase digoxin levels.

If a patient checks most of these boxes, a low‑dose trial of digoxin is reasonable.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even experienced cardiologists slip up with digoxin. Here are the top three mistakes:

- Over‑dosing in the elderly: Reduce the dose and monitor serum levels within a week.

- Ignoring renal decline: Re‑check eGFR every 3 months; adjust dosing promptly.

- Combining with other QT‑prolonging drugs: Avoid concurrent amiodarone or high‑dose verapamil unless absolutely necessary.

Following a structured monitoring plan cuts toxicity risk dramatically.

Future Directions: Ongoing Trials

Two large RCTs are expected to settle the digoxin debate in HFpEF:

- DIAGNOSE‑HFpEF (2025‑2028): Enrolling 3,000 HFpEF patients, randomized to digoxin 0.125 mg vs placebo, primary endpoint is composite of cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization.

- DIG‑HFpEF‑2 (2024‑2027): Focuses on patients with both HFpEF and atrial fibrillation, testing whether digoxin adds benefit on top of SGLT2 inhibitors.

Results due 2029 will likely update ESC and AHA/ACC guidelines.

Bottom Line for Clinicians

Digoxin isn’t a first‑line drug for diastolic heart failure, but it remains a useful tool in selected patients-especially those with uncontrolled atrial‑fibrillation rates or recurrent hospitalizations despite optimal therapy. Keep the dose low, monitor serum levels, and stay alert for drug interactions. As newer agents like SGLT2 inhibitors take center stage, expect digoxin’s role to become increasingly niche.

Can digoxin improve survival in HFpEF?

Current evidence does not show a clear mortality benefit. It may lower hospital readmissions in certain sub‑groups, but surviving longer isn’t guaranteed.

What is the recommended starting dose for an elderly patient?

For most patients over 75 years or with reduced renal function, start with 0.125 mg every other day and check the serum level after 7‑10 days.

Should digoxin be used if the patient is already on an SGLT2 inhibitor?

Yes, if the patient meets the selection criteria (e.g., atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response). There’s no known harmful interaction, but monitor for additive diuretic effects.

What are the early signs of digoxin toxicity?

Nausea, vomiting, visual disturbances (yellow‑green halos), and new arrhythmias such as premature ventricular beats are red flags. Check serum level immediately.

How often should serum digoxin be checked after stabilization?

Every 3‑6 months is typical, unless renal function changes or new interacting drugs are added.

10 Comments

Melanie Vargas

Hey folks 😊, great rundown on digoxin in HFpEF! It's cool to see the nuance between atrial fibrillation cases and pure diastolic failure. Remember to tailor the dose for older patients and keep an eye on kidney function. Happy prescribing! 🙌

Deborah Galloway

Totally agree, Melanie. The low‑dose strategy really does the trick for many seniors, and the monitoring schedule you mentioned can catch toxicity early. It’s also reassuring to have the guideline recommendations as a safety net.

Lisa Woodcock

From a broader perspective, the global data-like the Japan Diastolic HF study-highlight how practice patterns differ across regions. While some centers embrace digoxin early, others wait for SGLT2 breakthroughs. Balancing local expertise with international guidelines is key.

Sarah Keller

Look, the hype around digoxin in HFpEF is nothing but a nostalgic echo of outdated dogma.

The DIG trial subgroup barely nudged hospitalization rates and said nothing about mortality.

Yet clinicians cling to it because they fear any "new" drug might be too pricey.

The reality is that a low‑dose glycoside only modulates vagal tone, and that effect is marginal at best.

Meanwhile, robust evidence for SGLT2 inhibitors shows clear reductions in both death and hospital stays.

If you stack digoxin on top of a full guideline‑directed regimen, you’re just adding a pill with a razor‑thin therapeutic window.

The risk of arrhythmia, especially in the elderly with renal decline, outweighs the modest admission benefit.

Moreover, drug interactions with amiodarone or verapamil are practically inevitable in this comorbid population.

Physicians should demand hard outcomes, not surrogate markers, before persisting with a drug of dubious value.

The upcoming DIAGNOSE‑HFpEF trial might finally settle the debate, but until then, digoxin remains a niche curiosity.

Do not forget that patient adherence drops when you pile on another daily tablet with confusing dosing schedules.

In practice, I have seen more harm than good when digoxin is used indiscriminately.

Let’s be honest: we are better off optimizing beta‑blockers, ACE inhibitors, and especially SGLT2 agents first.

Only when a patient has refractory atrial fibrillation and repeated admissions should digoxin be considered, and even then at the lowest possible dose.

Anything beyond that is just therapeutic bravado masquerading as evidence‑based care.

Veronica Appleton

Bottom line digoxin can be useful in selected HFpEF patients especially those with atrial fibrillation who keep getting readmitted low dose 0.125 mg every other day is typically enough check levels after a week and adjust for kidney function

ram kumar

Ah, the glorification of a century‑old toxin-how quaint. One might wonder why we waste time on a drug that merely shuffles numbers without moving the needle on survival.

Charlie Stillwell

Enter the realm of “clinical inertia” where digoxin is paraded as a panacea 🧐-a relic of antiquated pathophysiology, drenched in outdated inotropic jargon. Such regimens perpetuate therapeutic dogma rather than foster innovation. 🚀

Ken Dany Poquiz Bocanegra

Use digoxin only if AFib persists despite optimal therapy.

krishna chegireddy

They don’t tell you that pharma pushes digoxin to hide the real cures. The data is filtered and the side effects are downplayed. Trust the silent voices.

Tamara Schäfer

I think the key is to re-evalute each patint individually 🙏. Even if the guidlines say "optional", many docotor still find it helpful. Keep an eye on renal funciton and you’ll avoid most issues. The future looks bright with newer agents tho.