Drug Withdrawal Timeline Calculator

Enter the approval and withdrawal dates to see how long it took for the FDA to remove a drug from the market. Compare to the new 180-day standard established in 2023.

Result Analysis

Time Between Approval & Withdrawal

New Standard Requirement

The FDA's new rules (2023) require withdrawals to be completed within 180 days after the issue is identified. The old system often took years.

For example, the Makena drug (approved 2011, withdrawn 2022) took 1,500 days - over 4 years. Under the new rules, this would have been resolved in just 6 months.

This tool shows why the 2023 law was so important. Faster withdrawals mean fewer patients receive ineffective treatments while the FDA reviews evidence.

Every year, drugs that once seemed promising are pulled from shelves. Patients stop taking them. Doctors stop prescribing them. Sometimes, it’s because a new side effect shows up. Other times, it turns out the drug never actually worked as promised. These aren’t rare glitches - they’re part of how medicine evolves. But the system that decides when to pull a drug has, for decades, been painfully slow. And that delay has real consequences.

How a Drug Gets Removed from the Market

There are two main ways a drug leaves the market: voluntary withdrawal and mandatory withdrawal. A company might pull its own drug because it’s not selling well, or because new data shows it’s riskier than expected. But the more serious cases - the ones that make headlines - happen when the FDA steps in.

The FDA doesn’t act on a hunch. It needs hard evidence. That evidence usually comes from post-approval studies. These are required after a drug gets approved, especially if it was fast-tracked under accelerated approval. Accelerated approval lets drugs reach patients faster, often based on early signs of benefit - like shrinking tumors - rather than proof they extend life. But the catch? The company must prove later that the drug actually helps. If they don’t? The FDA can remove it.

Before 2023, this process could take years. The FDA had no clear timeline. A drug might be flagged as ineffective in a 2020 study, but stay on the market until 2024. That’s not just bureaucratic delay - it’s patients continuing to get a treatment that doesn’t work, while still facing its risks.

The Makena Case: A System That Failed

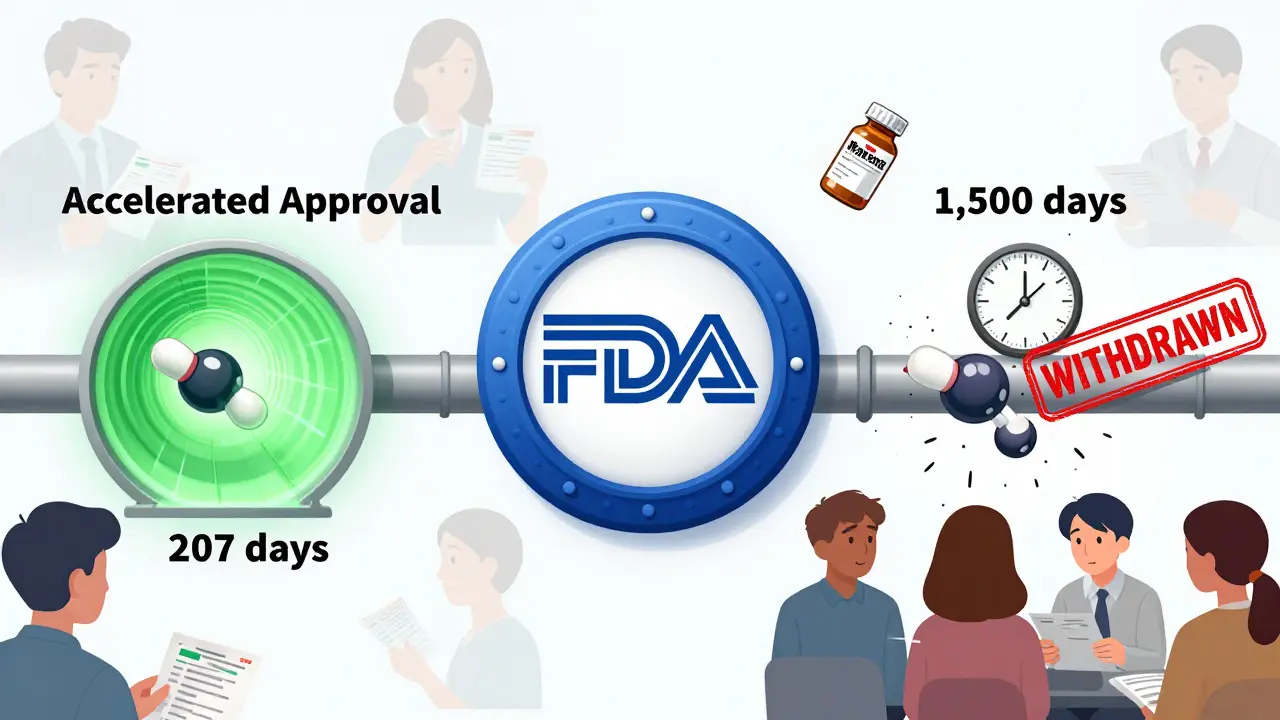

The most infamous example is Makena, a drug approved in 2011 to prevent preterm birth in high-risk women. The approval was based on a small, flawed study. By 2020, a much larger, better-designed trial showed it had no real benefit. The FDA should have acted fast. Instead, it took over four years - until 2022 - to finally withdraw approval.

During that time, thousands of women were given Makena. Many paid hundreds of dollars for a treatment that didn’t help. Some experienced side effects like blood clots, headaches, and swelling. The delay exposed a deeper flaw: the FDA’s approval process was faster than its withdrawal process. In Makena’s case, approval took 207 days. Withdrawal took 1,500 days. That’s a seven-to-one ratio.

It wasn’t just Makena. Between 2010 and 2020, about 12.7% of all drugs approved under accelerated pathways were eventually withdrawn. In oncology - where accelerated approval is common - nearly one in four approvals ended in removal. And in some cases, like a drug for small cell lung cancer, over 40% of eligible patients received it before it was pulled.

The 2023 Law That Changed Everything

In December 2023, Congress passed the Consolidated Appropriations Act. One section - 3210 - gave the FDA new power to act faster. Now, the agency can initiate withdrawal if:

- The company fails to complete required post-approval studies on time

- Those studies prove the drug doesn’t work

- Independent data shows the drug is unsafe or ineffective

- The company promotes the drug with false or misleading claims

This wasn’t just a tweak. It was a full overhaul. Before, sponsors could stall. The FDA had no real leverage. Now, the process has structure. The FDA must notify the company within 30 days. The company gets a chance to respond. A meeting can happen within 60 days. The final decision must come within 180 days. No more waiting five years.

The FDA didn’t wait to act. In August 2023, it issued its first withdrawal notice under the new rules - for an ALS drug that failed its confirmatory trial. It was a signal: the old system is over.

Why This Matters to Patients

If you’ve ever been prescribed a new cancer drug, or a treatment for a rare disease, you’ve likely been part of this system. Many of these drugs are approved under accelerated pathways because there are no good alternatives. That’s why they’re given a chance - but also why the stakes are so high.

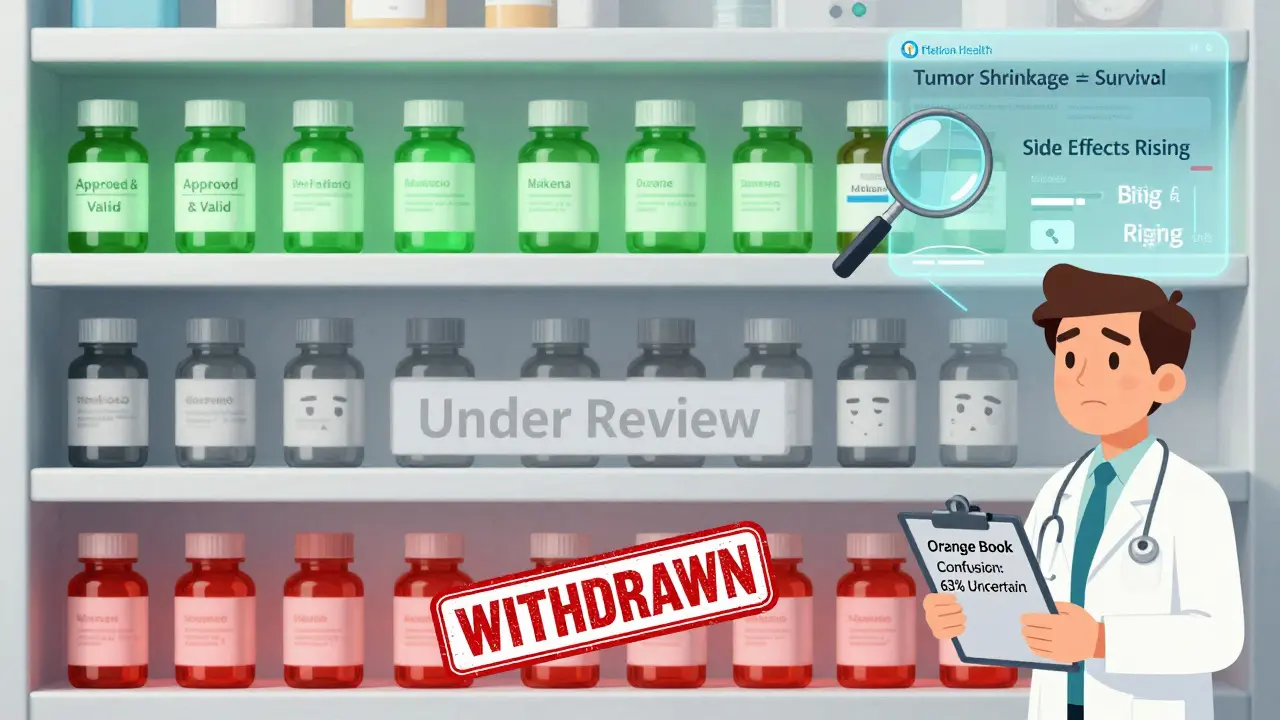

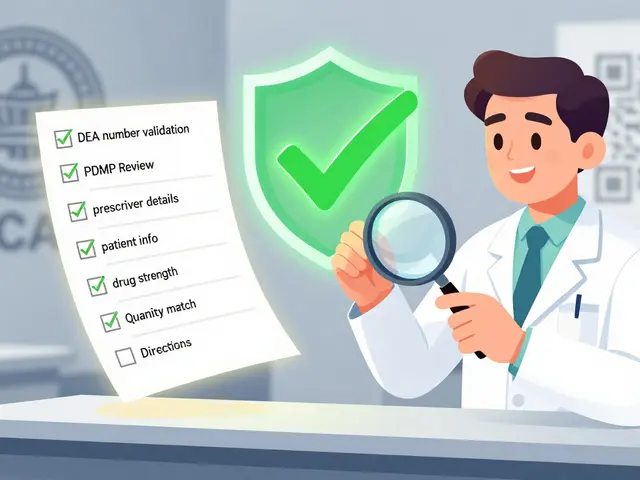

Patients don’t always know a drug is under review. Doctors might not either. Pharmacists struggle to interpret the Orange Book - the official list of approved drugs - because withdrawal statuses aren’t always clear. A 2022 survey found that 63% of pharmacists had trouble telling if a drug was still approved.

And when a drug is pulled? It’s messy. Oncology clinics report it takes an average of 72 hours just to find a replacement therapy. Insurance companies don’t always cover alternatives right away. Patients are left in limbo - worried, confused, and sometimes worse off than before.

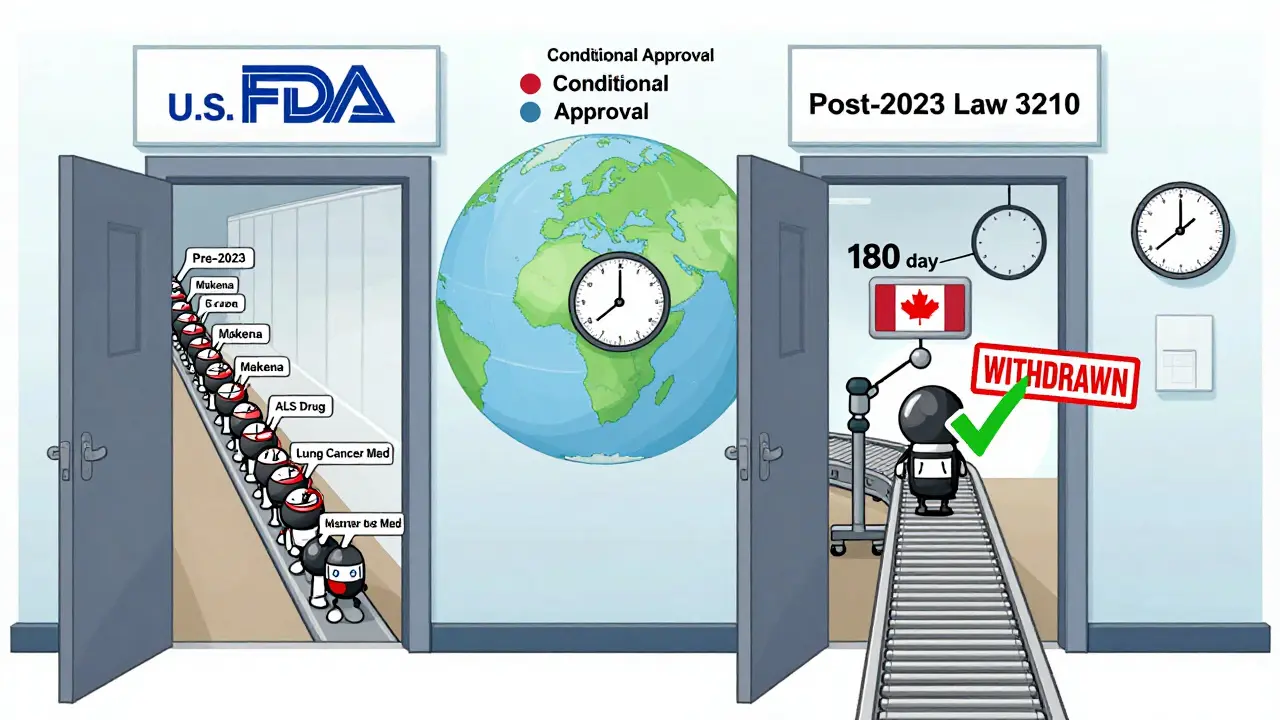

How the U.S. Compares to the Rest of the World

The U.S. used to be an outlier. In Europe and Canada, regulators often grant conditional approval. That means the drug comes with a built-in expiration date - if the company doesn’t prove effectiveness within a set time, the approval expires automatically.

The FDA didn’t have that tool. Instead, it relied on Postmarketing Required (PMR) studies, which companies could delay or ignore with little consequence. The 2023 law changed that. Now, the FDA can use similar conditional logic, especially for drugs approved under accelerated pathways.

This shift means the U.S. is finally aligning with global standards. It’s not about being stricter - it’s about being smarter. Conditional approval forces accountability from day one. No more waiting for a crisis to act.

What’s Next for Drug Safety?

The FDA is now building tools to catch problems faster. A pilot program launched in January 2024 uses real-world data from Flatiron Health - a network of cancer clinics - to monitor whether drugs actually help patients after approval. Instead of waiting for a formal trial, the agency can now see patterns in real time: Are patients living longer? Are they having more side effects? Are they being prescribed the drug for off-label uses?

By 2027, experts predict a 25% increase in drug withdrawals as these new tools take hold. That might sound alarming. But it’s not a sign of failure - it’s a sign of progress. More withdrawals mean fewer patients are stuck on drugs that don’t work.

Still, concerns remain. Some drugmakers warn that faster withdrawals could scare off innovation. If companies fear a drug will be pulled after a few years, will they still invest in risky areas like rare diseases? That’s a valid question. But the alternative - letting ineffective drugs stay on the market for years - is worse.

What You Can Do

If you’re taking a drug approved under accelerated approval, ask your doctor:

- Is this drug still under review for effectiveness?

- Has the company completed its required post-approval study?

- Is there a better, proven alternative?

Don’t assume a drug is safe just because it’s on the market. The system is improving, but it’s still imperfect. Stay informed. Ask questions. And if you’re prescribed a new treatment for a serious condition, make sure you understand the evidence behind it - not just the hope.

Medicine is not static. What works today might be pulled tomorrow. That’s not a flaw - it’s how science works. The real failure isn’t in removing drugs. It’s in taking too long to do it.

What’s the difference between a drug recall and a drug withdrawal?

A recall usually means a specific batch of a drug is contaminated or mislabeled - it’s a manufacturing issue. A withdrawal means the entire drug is pulled because it’s unsafe or ineffective - it’s a safety or effectiveness issue. Recalls are often temporary. Withdrawals are permanent.

Can a drug be withdrawn even if it’s still being sold?

Yes. The FDA considers a drug withdrawn from sale if the manufacturer stops distributing it - even if existing stock is still on pharmacy shelves. Once the FDA makes the official determination, pharmacies are expected to stop dispensing it. But in practice, some may continue selling leftover inventory until it runs out.

Why do some drugs get approved if they’re later found to be ineffective?

For serious illnesses with no other options, regulators allow drugs to be approved based on early signs of benefit - like tumor shrinkage - while requiring proof of real-world outcomes later. This is called accelerated approval. It gets life-saving drugs to patients faster, but it’s risky. If the later studies fail, the drug gets pulled. The problem wasn’t the approval - it was the delay in pulling it.

How do I find out if a drug I’m taking has been withdrawn?

Check the FDA’s Drug Safety Communications page or the Orange Book’s ‘Determination of Safety or Effectiveness’ list. Your pharmacist can also tell you if a drug is no longer approved. But don’t wait - if you’re on a drug approved under accelerated approval after 2010, ask your doctor proactively. Don’t assume they know.

Are generic versions of withdrawn drugs still available?

No. Once a brand-name drug is withdrawn for safety or effectiveness reasons, generic versions can no longer be approved or sold as substitutes. The FDA removes the drug from the Orange Book, which is the reference list for generics. If you see a generic version still on the shelf, it’s either outdated stock or illegally sold - report it.

9 Comments

Patrick Jarillon

So let me get this straight - the FDA lets a drug like Makena stay on the market for over a decade because ‘science takes time’? Nah. This ain’t science. This is Big Pharma playing chess with people’s lives. I’ve seen the documents. There’s a backroom deal between the FDA and pharma lobbyists. They don’t pull drugs because they’re dangerous - they pull them when the lawsuits get too loud. And don’t even get me started on how they bury the data. You think that ‘accelerated approval’ was for patients? Nah. It was a loophole to cash in before the truth came out. I’m not paranoid. I’m just the only one reading the fine print.

Sarah B

America leads the world in medical innovation and now we’re gonna start acting like Europe because some bureaucrat got mad? We don’t need conditional approval. We need more drugs not less. If you want to play it safe go to Canada. We got people dying every day waiting for cures and now we’re gonna make it harder to get them? No thanks

Tola Adedipe

I get the frustration but let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater. The 2023 law is a win. It’s not about slowing things down - it’s about making sure we don’t keep poisoning people while we wait for paperwork. The Makena case was a national embarrassment. I’ve worked in oncology for 15 years. I’ve seen patients lose months - sometimes years - on drugs that didn’t work. This isn’t about distrust. It’s about accountability. And honestly? The system was broken. Fixing it isn’t anti-innovation. It’s pro-patient.

Heather Burrows

I just think about how much energy we waste on this. Like we’re all so focused on pulling drugs after the fact instead of just… not approving them in the first place. Why do we keep letting drugs through on shaky data? It’s not that we’re slow to withdraw. It’s that we’re too eager to approve. And then we act shocked when the house of cards falls. Maybe we need less innovation and more humility.

Marcus Jackson

The whole accelerated approval thing was always a gamble. They knew it. Pharma knew it. Doctors knew it. But we all pretended it was a lifeline. Truth is? Most of those drugs never pan out. And now we’re finally saying - hey maybe we should stop pretending. The fact that 25% of oncology drugs get pulled? That’s not a bug. That’s the system working as intended. We just didn’t have the guts to admit it.

Lakisha Sarbah

i just asked my dr if my med was under review and he looked at me like i asked if the sky was made of cheese. like… why is this on me? if the fda cant keep track of what’s approved then why are we the ones who have to dig up the orange book? i just want to take my pill without doing homework

Paula Sa

I think we need to reframe this. It’s not about withdrawal being bad. It’s about how we treat people when a drug gets pulled. The system doesn’t fail because a drug gets pulled - it fails when we leave patients hanging. No one talks about the anxiety, the insurance battles, the months of uncertainty. We’re so focused on the science that we forget the humans. Maybe the real innovation isn’t in faster withdrawals - it’s in better support systems when they happen.

Joey Gianvincenzi

The regulatory framework of the United States has historically been characterized by a profound deference to corporate interests, often at the expense of public health. The introduction of enforceable timelines for post-marketing studies represents not merely a procedural adjustment, but a paradigmatic shift toward accountability. One must acknowledge that the previous model - where pharmaceutical entities could indefinitely defer evidentiary obligations - constituted a systemic moral hazard. The FDA’s newfound authority, while overdue, is not an overreach - it is a restoration of scientific integrity.

Jesse Lord

i just want to say thanks to whoever wrote this. i was on one of those drugs and i had no idea it was under review. my doc never told me. my pharmacist didn’t either. i only found out because i googled it after reading this. i feel like i got lucky. so many people don’t even know to look. if this helps even one person ask the right questions - it’s worth it