Alcohol-Related Diarrhea Risk Calculator

Assess Your Risk

Answer the following questions to determine your risk level for alcohol-induced chronic diarrhea.

Your Risk Assessment

Enter your information and click "Calculate My Risk" to see your assessment.

Ever wondered why a night out can leave you running to the bathroom for days? The link between chronic diarrhea and alcohol isn’t just a coincidence-there’s solid science behind it. Below we’ll break down what’s happening inside your gut, who’s most vulnerable, and what you can actually do to stop the cycle.

Key Takeaways

- Alcohol disrupts gut lining, microbiome balance, and intestinal motility, all of which can cause persistent loose stools.

- Dehydration, electrolyte loss, and liver stress amplify the problem.

- Reducing alcohol intake, staying hydrated, and addressing nutrient deficiencies often resolve symptoms.

- Seek medical help if diarrhea lasts longer than two weeks or is accompanied by blood, severe pain, or weight loss.

What Is Chronic Diarrhea?

Chronic diarrhea is defined as loose, watery stools occurring three or more times a day for at least four weeks. It’s more than an occasional upset-it signals ongoing irritation or malfunction of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Common signs include urgency, cramping, and frequent trips to the bathroom, often leading to dehydration and nutrient loss.

How Does Alcohol Affect the Gut?

Alcohol consumption refers to the intake of ethanol‑containing beverages, ranging from occasional drinks to heavy, daily use. When you drink, ethanol and its by‑products travel straight to the stomach and small intestine, where they can irritate the mucosal lining, alter secretions, and change the balance of good and bad bacteria.

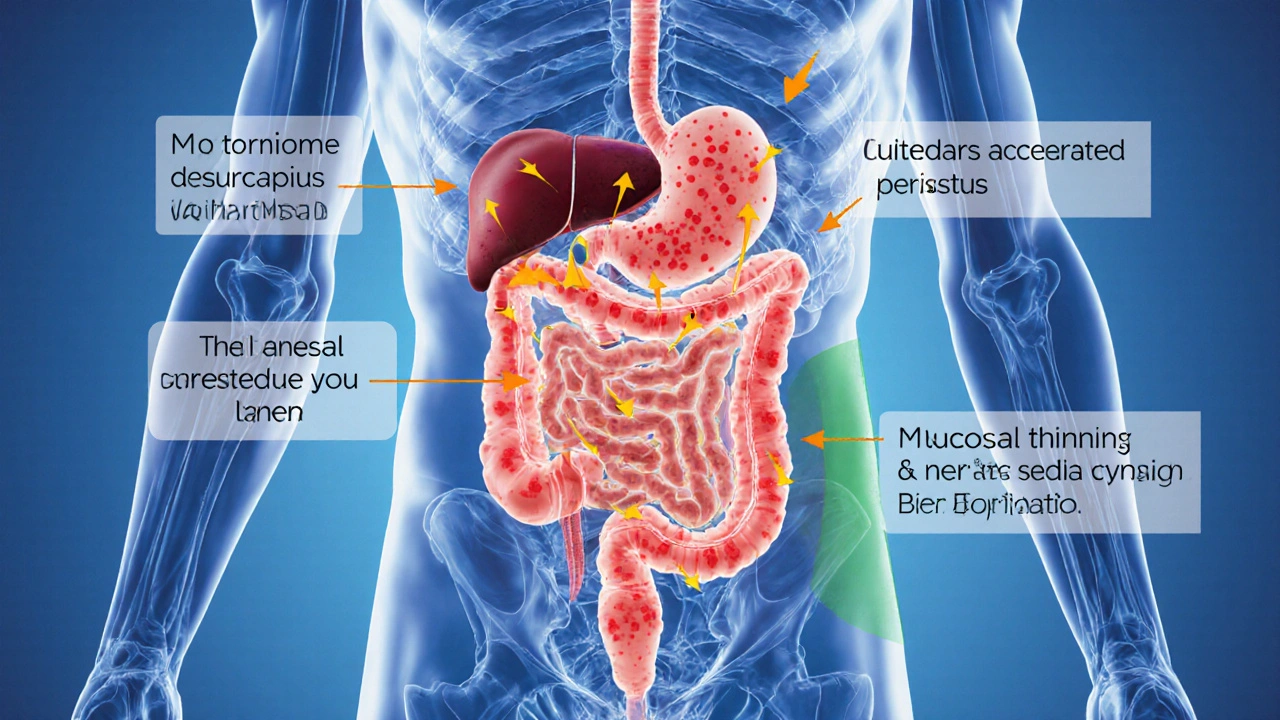

The Biological Pathways Linking Alcohol to Chronic Diarrhea

Several mechanisms work together to turn a night of drinking into a lingering digestive nightmare:

- Gut microbiome disruption - Alcohol wipes out beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacteria while allowing harmful strains to flourish. This imbalance provokes inflammation and impairs nutrient absorption, setting the stage for watery stools.

- Intestinal motility changes - Ethanol stimulates the release of serotonin in the gut, speeding up peristalsis. Faster transit means less water reabsorption, so stool stays loose.

- Mucosal damage - Alcohol is a direct irritant. Repeated exposure thins the protective mucus layer, exposing epithelial cells to toxins and leading to chronic inflammation.

- Liver function compromise - The liver metabolizes ethanol into acetaldehyde, a highly toxic compound. When the liver is overburdened, bile production can falter, and bile acid malabsorption contributes to diarrhea.

- Electrolyte imbalance and Dehydration - Frequent watery stools flush out sodium, potassium, and magnesium. Low electrolyte levels further impair gut muscle function, creating a feedback loop.

Who Is Most at Risk?

Not everyone who drinks will develop chronic diarrhea, but certain groups are more vulnerable:

- Heavy drinkers (more than 14 drinks per week for men, 7 for women) - the dose‑response relationship is clear.

- People with pre‑existing GI conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) - alcohol can trigger flare‑ups.

- Individuals with Alcohol Use Disorder - chronic consumption leads to cumulative gut damage.

- Those taking medications that irritate the stomach (e.g., NSAIDs, certain antibiotics) - combined effects worsen diarrhea.

Spotting Alcohol‑Induced Chronic Diarrhea

Distinguishing alcohol‑related stool issues from other causes helps you act fast. Look for these clues:

- Onset within hours to a day after drinking, persisting beyond the usual “hangover” period.

- Stools that are pale, frothy, and watery without blood.

- Accompanying symptoms such as abdominal cramping, nausea, and a burning sensation after meals.

- Signs of dehydration: dry mouth, dark urine, dizziness.

- Improvement on days you skip alcohol.

Managing and Preventing Alcohol‑Induced Chronic Diarrhea

Stopping the cycle isn’t about a quick fix; it’s a blend of lifestyle tweaks and, if needed, medical support.

1. Cut Back or Stop Drinking

The most effective step is reducing ethanol intake. Even cutting down to low‑risk levels (≤1 drink per day for women, ≤2 for men) can dramatically improve gut health.

2. Re‑hydrate Smartly

Replace lost fluids with oral rehydration solutions that include sodium, potassium, and glucose. Coconut water or a pinch of salt in water works in a pinch.

3. Restore the Microbiome

Probiotic supplements containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bifidobacterium lactis have shown 30% reduction in alcohol‑related diarrhea in clinical trials. Fermented foods-yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut-are also helpful.

4. Nutrient Support

Alcohol depletes B‑vitamins and zinc. A daily B‑complex and 30mg zinc gluconate can aid mucosal healing and enzyme function.

5. Medications

If dietary changes aren’t enough, doctors may prescribe loperamide for symptomatic relief or bismuth subsalicylate to protect the lining. In cases of severe malabsorption, antibiotics like rifaximin target bacterial overgrowth.

6. Address Underlying Liver Issues

Persistent liver inflammation (e.g., fatty liver disease) needs specific management-weight loss, hepatoprotective agents, and abstinence.

When to Seek Professional Help

Most bouts improve within a week of cutting alcohol, but you should contact a healthcare provider if you notice any of the following:

- Diarrhea lasting longer than 14days.

- Blood, mucus, or a black tarry stool.

- Severe abdominal pain or fever.

- Unexplained weight loss (>5% of body weight).

- Signs of severe dehydration (rapid heartbeat, low blood pressure, confusion).

Comparison Table: Common Causes of Chronic Diarrhea vs. Alcohol‑Induced Diarrhea

| Aspect | General Chronic Diarrhea | Alcohol‑Induced Diarrhea |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Triggers | Infections, IBD, celiac disease, medications | Excessive ethanol intake, binge drinking |

| Onset after trigger | Variable - days to weeks | Hours to 1day |

| Stool characteristics | May contain blood, mucus, or be fatty | Watery, pale, often frothy; no blood |

| Associated symptoms | Fever, weight loss, abdominal pain | Dehydration, abdominal cramping, hangover symptoms |

| Primary treatment | Targeted therapy (antibiotics, immunosuppressants) | Alcohol reduction, rehydration, probiotics |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can occasional drinking cause chronic diarrhea?

In most cases, a single night of drinking leads to short‑term loose stools that resolve within 24‑48hours. Chronic diarrhea usually requires repeated or heavy alcohol use that continuously damages the gut lining.

Is it safe to use over‑the‑counter anti‑diarrheal meds while drinking?

Mixing loperamide with alcohol isn’t advisable because both slow gut motility; this can lead to severe constipation or toxic buildup. Talk to a doctor before combining any medication with alcohol.

How long does it take for the gut to recover after stopping alcohol?

Mucosal repair begins within a few days, but full microbiome balance may take 2‑4weeks of abstinence, especially if the person had a long history of heavy drinking.

What probiotic strains are most effective for alcohol‑related gut issues?

Clinical data highlight Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Bifidobacterium lactis as having the strongest protective effect against ethanol‑induced barrier disruption.

When should I get lab tests for chronic diarrhea?

If symptoms persist beyond two weeks, or if you notice blood, weight loss, or severe dehydration, a doctor will likely order stool cultures, CBC, inflammatory markers, and perhaps a colonoscopy to rule out other conditions.

16 Comments

Jayant Paliwal

Alcohol, especially in excess, agitates the intestinal lining, prompting hypersecretion of fluids that precipitate loose stools.

The ethanol molecule disrupts the tight junctions between enterocytes, thereby increasing permeability and allowing electrolytes to leak into the lumen.

This osmotic imbalance compels the colon to draw water from the bloodstream, accelerating transit time.

Moreover, chronic consumption induces inflammation mediated by cytokines such as TNF‑α and interleukin‑6, which further irritate the gut mucosa.

The repeated inflammatory insult can damage the villi, reducing absorptive capacity and exacerbating diarrheal output.

Alcohol also perturbs the composition of the microbiota, fostering overgrowth of pathogenic strains while suppressing beneficial bifidobacteria.

Dysbiosis, in turn, generates bacterial metabolites that stimulate secretory pathways in the colon.

For individuals with pre‑existing gastrointestinal disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome, the irritant effect of alcohol is magnified.

Concurrent use of non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs can synergistically impair the protective mucus layer, leaving the epithelium vulnerable.

The liver’s role in metabolising ethanol produces acetaldehyde, a toxic intermediate that can further injure the gut barrier through oxidative stress.

Acetaldehyde also interferes with the enteric nervous system, altering motility patterns and promoting rapid passage of contents.

Genetic polymorphisms in aldehyde dehydrogenase may render some individuals particularly susceptible to these effects.

Clinically, patients often report that symptoms intensify after binge‑drinking episodes, suggesting a dose‑dependent relationship.

Management strategies therefore emphasise reduction or cessation of alcohol intake, alongside rehydration and electrolyte replacement.

In refractory cases, probiotic supplementation and targeted anti‑inflammatory agents can help restore mucosal integrity and alleviate chronic diarrhea.

Kamal ALGhafri

While the correlation between ethanol intake and stool frequency is well‑documented, the underlying pathophysiology hinges on mucosal permeability and microbial dysbiosis.

Alcohol’s direct cytotoxicity compromises the epithelial barrier, allowing luminal contents to trigger secretory reflexes.

Additionally, the metabolic by‑product acetaldehyde imposes oxidative stress that aggravates inflammation.

Individuals with baseline irritable bowel syndrome often experience amplified symptoms due to this sensitization.

Thus, moderation remains the most pragmatic preventive measure.

Gulam Ahmed Khan

Great point about the gut barrier! 😊 Alcohol really does sabotage the tight junctions, but the good news is that we can rebuild them with proper nutrition and probiotic support.

👍 Stay hydrated, choose low‑alcohol options, and give your intestines a chance to heal.

Remember, small consistent changes often trump drastic bans.

Keep the optimism alive and your gut will thank you!

John and Maria Cristina Varano

i think american beers are worst for the gut we should stop drinking them

Stan Oud

While your optimism is noted; the biochemical cascade induced by ethanol remains indisputably complex; yet, the restorative potential of diet cannot be dismissed.

Ryan Moodley

Ah, the classic nationalist lament! One must recognize that blaming a single nation's brew oversimplifies a global metabolic truth.

Alcohol, regardless of origin, operates under identical enzymatic principles, and any attempt to single out a culture is both naïve and intellectually lazy.

In truth, the gut's response is dictated by dose, frequency, and individual genetics, not patriotism.

So let us rise above parochial rhetoric and confront the universal chemistry!

carol messum

Life is a series of choices, and the decision to sip or abstain shapes the quiet rhythm of our digestion.

Simple habits echo in complex systems.

Jennifer Ramos

Absolutely, your words resonate with me 😊.

Small mindful choices truly cascade into better health.

Let’s keep encouraging each other!

Grover Walters

Your encouragement aligns with current recommendations emphasizing gradual lifestyle adjustments.

Empirical studies confirm that incremental reductions in alcohol intake produce measurable improvements in bowel regularity.

Amy Collins

The article overcomplicates a simple gut issue.

maurice screti

When one attempts to distill the intricate interplay between ethanol metabolism and intestinal homeostasis into a handful of bullet points, the resultant narrative inevitably suffers from a reductionist myopia.

Yet, the author, perhaps motivated by a desire for accessibility, elects to veil the cascade of enzymatic transformations, microbial perturbations, and neurogastroenteric signaling behind a veneer of superficiality.

Such an approach, while commendable in its intent to reach a broader audience, paradoxically undermines the intellectual rigor that the subject commands.

A more erudite exposition would have elucidated the role of cytochrome P450 isoforms, the significance of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase polymorphisms, and the downstream effects on mucosal immunity.

In doing so, readers would be equipped not merely with prescriptive advice but with a conceptual framework to navigate their own physiological responses.

Thus, while the article serves as a cursory primer, the discerning scholar must seek supplemental literature to attain a comprehensive understanding.

Abigail Adams

Your critique is methodologically sound; the omission of enzymatic detail represents a notable gap.

Future revisions should incorporate peer‑reviewed references to substantiate the proposed mechanisms.

Mia Michaelsen

Empirical evidence unequivocally demonstrates that ethanol disrupts tight junction proteins, thereby increasing intestinal permeability, a phenomenon often termed ‘leaky gut.’

Concurrently, alterations in the gut microbiome exacerbate secretory diarrhea.

Consequently, clinicians should assess alcohol intake when evaluating chronic gastrointestinal complaints.

Kat Mudd

Indeed the cascade begins at the mucosal surface where ethanol interacts with enterocytes changing their polarity leading to a cascade of ion channel dysregulation that propels water into the lumen subsequently accelerating transit time and compounding the diarrheal output this chain reaction underscores why moderation cannot be overstated

Pradeep kumar

Your breakdown is spot‑on; the pathophysiology you described aligns with current gastro‑enterology literature.

By integrating probiotic therapy and dietary fiber, we can modulate the dysbiosis and reinforce barrier function, ultimately mitigating symptoms.

Keep up the great analytical work!

James Waltrip

One must also consider the covert influence of the alcohol industry, whose funding of selective research subtly shapes the narrative, obscuring the true extent of gut damage.

Their vested interests perpetuate misinformation, compelling the public to underestimate the systemic repercussions of habitual drinking.

It is a moral imperative to expose these hidden agendas and advocate for transparent, unbiased science.