TTP Medication Risk Assessment Tool

This tool helps you understand your risk of medication-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) based on the medications you're taking. TTP is a rare but life-threatening blood disorder that can develop after taking certain drugs.

When a drug you took for a common problem suddenly turns deadly, it’s not just rare - it’s terrifying. Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura, or TTP, triggered by medications, is one of those hidden dangers. It doesn’t show up in warning labels like nausea or dizziness. It strikes silently, shredding platelets, tearing apart red blood cells, and shutting down organs - often before you realize something’s wrong. And the worst part? Many doctors miss it.

What Exactly Is Drug-Induced TTP?

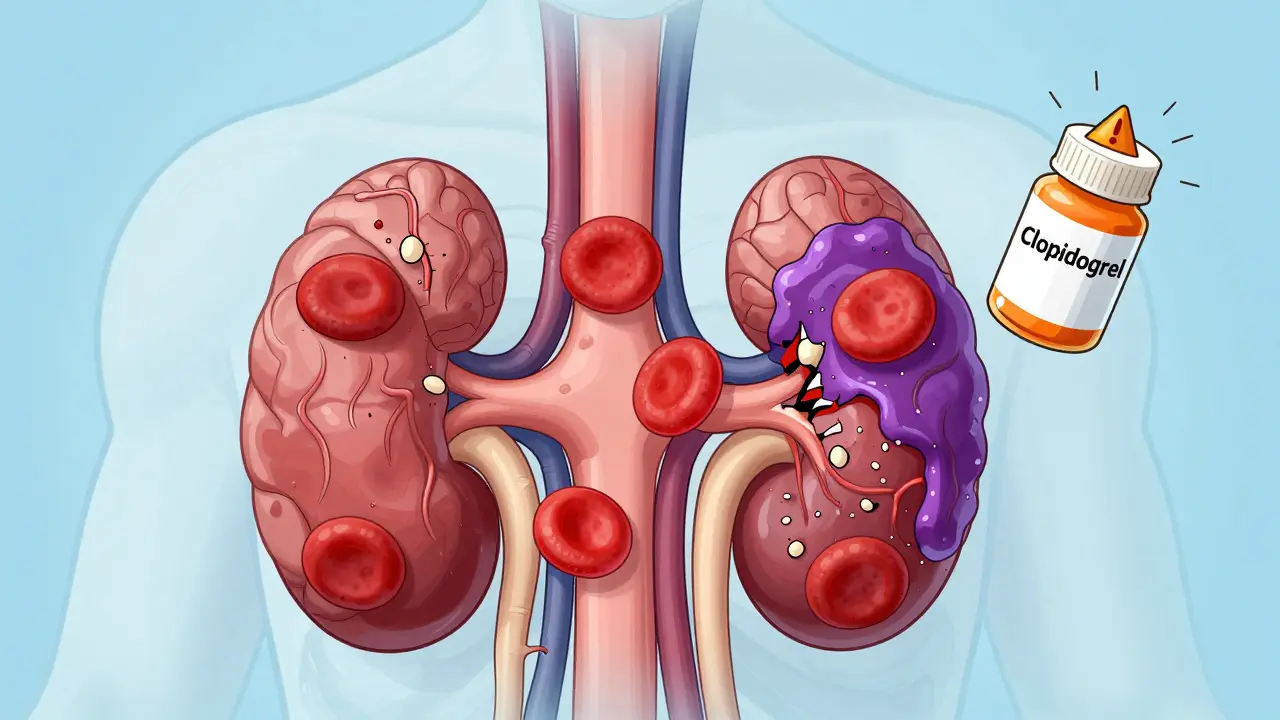

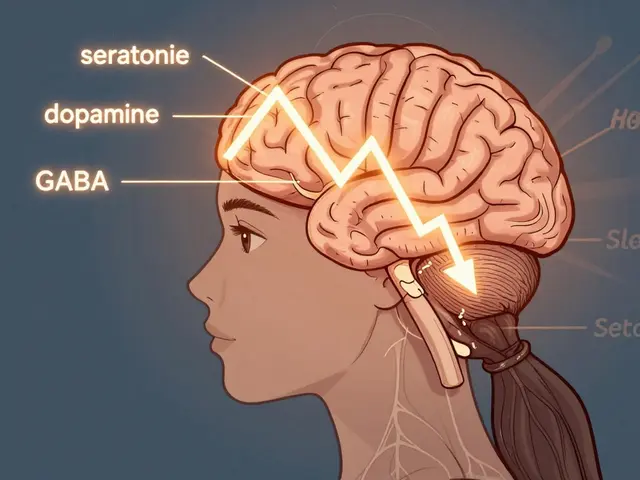

TTP isn’t just low platelets. It’s a full-body crisis. Your blood starts forming clots where it shouldn’t - in tiny vessels from your brain to your kidneys. These clots use up your platelets so fast that your count crashes below 50,000 per microliter (normal is 150,000-450,000). At the same time, red blood cells get ripped apart as they squeeze through these clots, turning into jagged fragments called schistocytes. That’s microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. You’ll feel exhausted, jaundiced, and confused. Some people have seizures. Others go into kidney failure. Without treatment, half of patients die within a week.

There are two main ways drugs cause this. The first is immune-mediated. Your body makes antibodies that latch onto platelets - but only when the drug is present. Think of it like a key (the drug) that unlocks a deadly mechanism. Once you stop the drug, the key disappears, and the body starts to heal. The second way is direct toxicity. Some drugs, like cyclosporine or mitomycin C, slowly damage the lining of your blood vessels over months. The damage builds up until your vessels start clotting uncontrollably.

Which Medications Are the Biggest Risks?

Over 300 drugs have been linked to TTP, but only a handful carry real, proven danger. The top five, backed by hundreds of case reports, are:

- Quinine - found in tonic water and some leg cramp pills. One case per 10,000 prescriptions. But if you drink 2-3 glasses of tonic water daily for weeks, your risk spikes. There are documented cases of people developing TTP from what they thought was just a nightcap.

- Clopidogrel (Plavix) - a common blood thinner. About 1 in 26,000 users get TTP. Symptoms usually appear within 2 weeks of starting it.

- Ticlopidine - older than clopidogrel, but far more dangerous. It caused 1 case per 1,600 users, which is why it was pulled from most markets.

- Cyclosporine - used after organ transplants. Risk jumps to 1.5-15% if the dose is over 5 mg/kg/day.

- Mitomycin C - a chemotherapy drug. TTP here isn’t immune-driven; it’s pure toxicity. It can take 6-12 months to show up.

Newer drugs like TNF-alpha inhibitors (adalimumab, certolizumab) and cancer immunotherapies (nivolumab, pembrolizumab) are now showing up in reports. They’re not common culprits, but they’re rising fast.

Why Is It So Often Missed?

TTP looks like a lot of other things. Low platelets? That’s ITP. Fatigue and confusion? Maybe sepsis or the flu. Kidney trouble? Could be acute nephritis. In fact, 72% of patients in Reddit patient forums said they were misdiagnosed at first. One woman in a 2019 BMJ case report was treated for migraines for three weeks before someone finally looked at her blood smear and saw the schistocytes. By then, she had a stroke.

Doctors don’t test for TTP unless they’re thinking about it. And most aren’t. The key is recognizing the pattern: low platelets + broken red blood cells + neurological or kidney symptoms = TTP until proven otherwise. No other condition causes all three together like this.

How Is It Diagnosed?

There’s no single test. Diagnosis is a puzzle. The classic signs are:

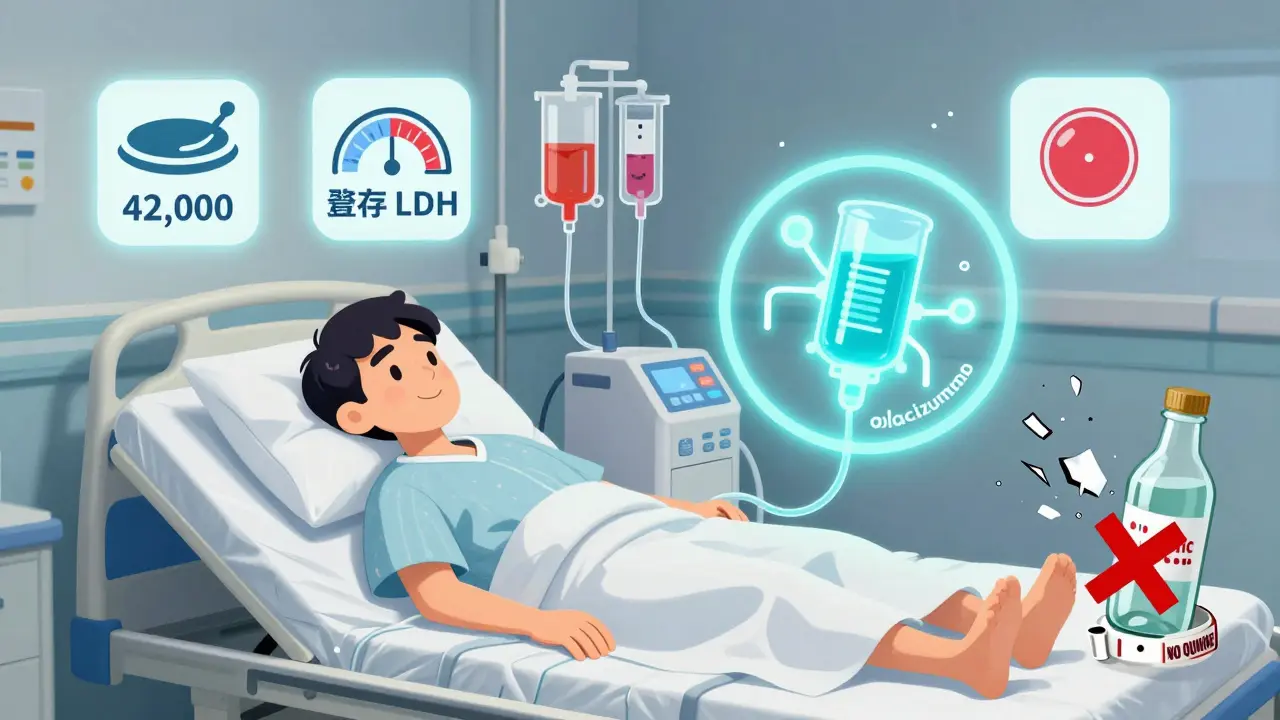

- Platelet count under 150,000 (often under 50,000)

- Schistocytes on a blood smear

- Elevated LDH (over 500 U/L)

- Undetectable haptoglobin

- No other explanation (like DIC, lupus, or infection)

The gold standard is measuring ADAMTS13 enzyme activity. If it’s below 10%, you’ve got immune-mediated TTP. But waiting for results can be deadly. Treatment must start within hours - not days. That’s why guidelines say: if the clinical picture fits, begin plasma exchange immediately, even before lab results come back.

What’s the Treatment?

For immune-mediated TTP (quinine, clopidogrel, ticlopidine), plasma exchange is the lifeline. It removes the bad antibodies and replaces them with healthy plasma. About 80% of patients recover if treated within 4-8 hours. Daily treatments continue until platelets stay above 150,000 for two days straight.

For toxicity-driven TTP (cyclosporine, mitomycin C), plasma exchange doesn’t help much. The only cure is stopping the drug. Then you wait - sometimes for months - while your blood vessels repair themselves. Supportive care like dialysis or blood transfusions keeps you alive until recovery.

New drugs like caplacizumab are changing the game. It blocks the clotting process at the source and cuts recovery time by nearly half. But it costs $18,500 per course. Most hospitals can’t stock it. Only major centers use it regularly.

What Happens After?

Survivors aren’t always back to normal. One in three still feels exhausted six months later. Some have lasting brain fog or kidney damage. And here’s the scary part: if you had TTP from quinine or clopidogrel, you can never take those drugs again. Even a tiny amount - like a sip of tonic water - can trigger a relapse. Years later. Your immune system remembers.

That’s why doctors now ask: “Have you taken any new meds or supplements in the last 30 days?” - not just prescriptions, but over-the-counter pills, herbal remedies, and even tonic water. In 23% of quinine-related cases, the trigger wasn’t a pill - it was a drink.

How to Protect Yourself

If you’re on any of these drugs - especially clopidogrel, cyclosporine, or anything with quinine - watch for these red flags:

- Sudden unexplained bruising or petechiae (tiny red dots on skin)

- Unusual fatigue, pale skin, or yellowing eyes

- Headaches, confusion, slurred speech, or seizures

- Decreased urine output or swelling in legs

Don’t wait for your next appointment. If you notice even one of these after starting a new drug, go to the ER and say: “I’m worried about TTP.” Bring a list of everything you’ve taken - including supplements and tonic water.

And if you’ve had TTP before? Never take the triggering drug again. Period. Your risk of recurrence is extremely high. Keep a medical alert card or bracelet listing the drugs you can’t take.

The Bigger Picture

Drug-induced TTP is rare - about 1 in 100,000 people per year. But it’s deadly. And it’s getting more common. TTP reports to the FDA jumped 37% between 2015 and 2022. Biologic drugs, cancer immunotherapies, and even common OTC products are now on the radar. The FDA has issued black box warnings for quinine and ticlopidine. The European Medicines Agency now requires drug developers to screen for TTP potential during clinical trials.

But the real problem isn’t the drugs - it’s the lack of awareness. The mortality rate hasn’t dropped since the 1990s. Why? Because too many patients are diagnosed too late. Education is the missing link. Patients need to know. Doctors need to think about it. And everyone needs to understand that a simple drink of tonic water can be as dangerous as a prescription drug.

Drug-induced TTP isn’t something you can ignore. It doesn’t care if you’re young, healthy, or took the drug for a minor reason. It strikes fast. It kills fast. But if you know the signs - and act fast - you can survive it.

12 Comments

Rob Deneke

I had no idea tonic water could do this. My dad drinks it every night for leg cramps. Gonna make him stop ASAP. Thanks for the heads up.

Bianca Leonhardt

People are idiots. You think a drink is harmless? You take random supplements, you get a blood clot, you blame the system. Wake up.

brooke wright

I had TTP after taking Plavix for a stent. They didn't catch it for five days. I was in ICU, organs shutting down, my husband thought I was dying. I'm alive but I still get dizzy sometimes. And yes I never drink tonic water anymore. Not even a splash. Ever.

Nick Cole

This is one of those posts that should be mandatory reading for every ER doc and primary care provider. The fact that 72% get misdiagnosed is criminal. We need better training, not just more warnings.

waneta rozwan

I read this and cried. My sister died from this. They told her it was the flu. She was 34. They didn't even look at her blood. Now I scream at every doctor I meet: CHECK THE SMEAR. CHECK THE SMEAR. CHECK THE SMEAR.

Nicholas Gabriel

I'm a nurse in oncology, and I've seen mitomycin C cause TTP twice. It's terrifying. The key is: if a patient has unexplained cytopenias + fatigue + neurological symptoms after chemo, don't wait for the ADAMTS13 result. Start plasma exchange. NOW. Don't wait for permission. Don't wait for the attending. Do it.

Cheryl Griffith

I'm so glad someone wrote this. I've been telling my friends for years: if you're on anything new and feel off, go to the ER and say TTP. Don't say 'I feel weird.' Say the word. It's a code. It saves lives.

swarnima singh

this is why modern medicine is broken. we trust pills like theyre magic. but the body knows. the body remembers. you poison it with chemicals, it fights back. even tonic water? its not the water its the sin of forgetting nature. we are not machines. we are souls with blood. and you cant play god with enzymes and expect mercy.

Jody Fahrenkrug

I work in a pharmacy. We now have a little note in our system: 'Ask about tonic water if patient is on clopidogrel.' It’s a tiny thing. But it’s saved at least three people this year.

Allen Davidson

Caplacizumab is amazing but it's a band-aid. The real fix is stopping the drugs that cause this in the first place. Why are we still selling quinine in OTC leg cramp pills? That's not healthcare. That's corporate negligence.

john Mccoskey

Let's be real. The FDA doesn't care. They approve drugs based on profit margins and trial duration, not long-term rare toxicity. TTP is statistically insignificant to them. 1 in 100,000? That's not a crisis. That's a footnote. Until it's your kid. Then suddenly it's a tragedy. The system is designed to ignore the outliers. And the outliers die.

Joie Cregin

I used to think tonic water was just a fancy mixer. Now I look at it like it's a loaded gun. I told my mom to stop drinking it after she had a weird rash. She laughed. Then she Googled it. Now she drinks sparkling water with lime. Smart move. We don't need to be heroes. We just need to be careful.