When your liver is damaged, blood doesn’t flow through it the way it should. Instead, pressure builds up in the portal vein-the main blood vessel that carries blood from your intestines to your liver. This is portal hypertension. It’s not a disease on its own, but a dangerous consequence of liver damage, most often from cirrhosis. And left unchecked, it leads to life-threatening problems: swollen veins in your esophagus that can burst, fluid building up in your belly, confusion from toxins your liver can’t filter, and kidney failure. This isn’t theoretical. Every year, tens of thousands of people with advanced liver disease face these exact complications. The good news? We know how to manage them-if you act early and follow the science.

What Causes Portal Hypertension?

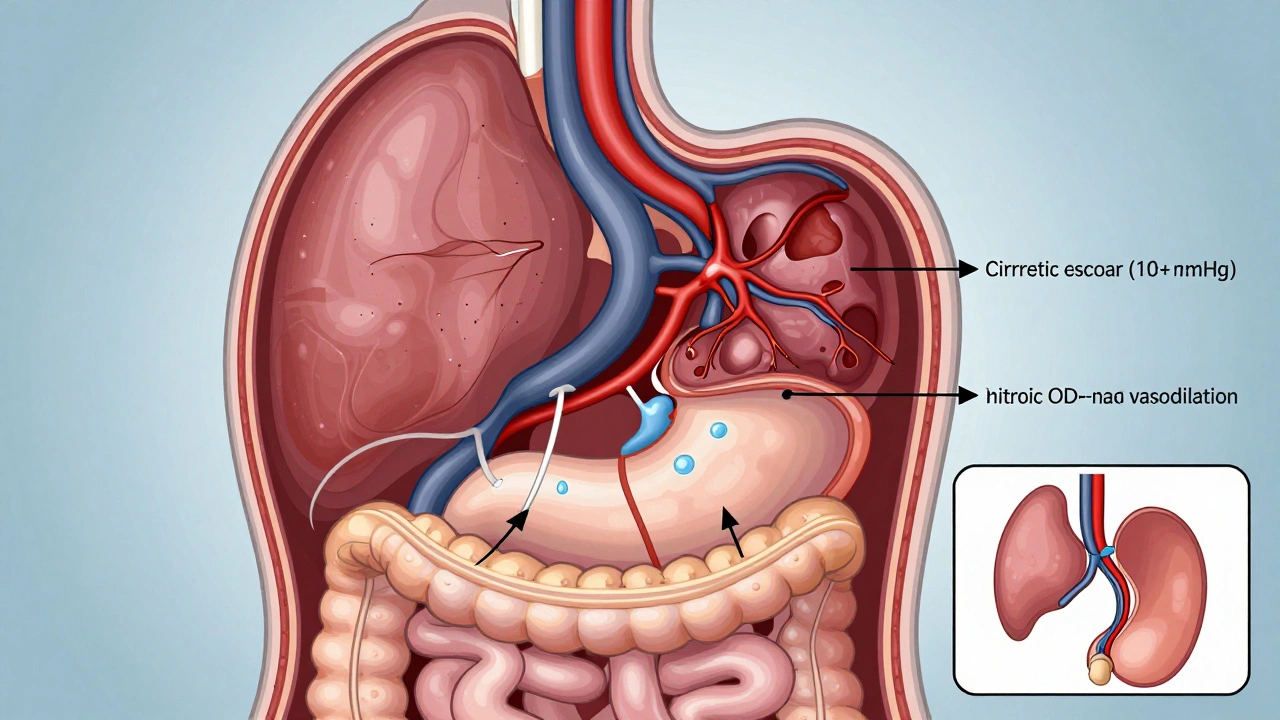

Portal hypertension happens when blood flow through the liver gets blocked. The most common reason? Cirrhosis. About 90% of cases come from scar tissue replacing healthy liver cells. That scar tissue squeezes the tiny blood vessels inside the liver, forcing blood to find other routes. But here’s the twist: it’s not just about blockage. Your body also starts producing more nitric oxide, which causes blood vessels in your intestines to widen. That means even more blood rushes toward the liver-only now, it can’t get through. The result? Pressure climbs. Normal portal pressure is 5-10 mmHg. Once it hits 10 mmHg or higher, or if the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) exceeds 5 mmHg, you’re in clinically significant portal hypertension.That 10 mmHg threshold isn’t arbitrary. It’s based on decades of research, including the Baveno VI and VII consensus guidelines. It’s the point where complications like varices and ascites start appearing. About 70% of people with cirrhosis develop this level of pressure within five years of diagnosis. And it’s getting worse. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is now behind 24% of cirrhosis cases in the U.S. and Europe-up from 15% just a decade ago. That means more people are at risk, and faster.

Varices: The Silent Time Bomb

One of the most dangerous outcomes of portal hypertension is varices-swollen, fragile veins in your esophagus or stomach. Think of them like overstretched garden hoses. They’re not supposed to be there. Blood is forced to find new paths because the liver is clogged. These veins balloon under pressure, their walls thinning until they rupture. Half of all cirrhotic patients develop varices within 10 years. And once they’re there, the risk of bleeding is real: 5% to 15% per year for medium to large varices.When a varix bleeds, it’s an emergency. People describe it as vomiting liters of bright red blood. Some pass black, tarry stools. Others just feel dizzy, weak, or faint. Around 15-20% of patients die within six weeks of their first major bleed. That’s why prevention is everything.

For patients with medium or large varices, the standard is clear: start a non-selective beta-blocker like propranolol. The goal? Lower your resting heart rate by 25%. That simple target reduces the chance of first bleeding by 45%. If you can’t take beta-blockers, or if they don’t work, endoscopic band ligation is the next step. It’s a procedure where a doctor uses a scope to place tiny rubber bands around the varices, cutting off blood flow. After treatment, rebleeding drops from 60% to under 30%.

But here’s the catch: even after successful treatment, 60% of patients will rebleed within a year if they don’t get both beta-blockers and band ligation together. That’s why guidelines now recommend combination therapy for high-risk patients. And if you’ve already bled once, you’re in a high-risk group. Secondary prevention isn’t optional-it’s life-saving.

Ascites: When Your Belly Fills With Fluid

Another major complication? Ascites. That’s when fluid leaks from blood vessels in your liver and collects in your abdomen. About 60% of people with cirrhosis develop ascites within 10 years. At first, it’s just mild bloating. But as it grows, your belly swells like a water balloon. You can’t eat much. You get short of breath. Walking becomes hard. Some patients say it feels like a tire iron is pressed into their stomach.The treatment starts with diet. Cut sodium to under 2,000 mg a day. That means no processed food, no canned soups, no soy sauce. Then come the diuretics: spironolactone (starting at 100 mg daily) and furosemide (40 mg daily). Together, they pull fluid out through your kidneys. For most people, this works. Around 95% of those with uncomplicated ascites see improvement.

But if your belly is tight, painful, and you’re struggling to breathe, you need a paracentesis-where a needle drains the fluid. It’s quick. It helps immediately. But here’s the rule: every liter of fluid removed, you need 6-8 grams of albumin (a protein) given intravenously. Skip the albumin, and your blood pressure crashes. Your kidneys can fail. That’s why this isn’t just a drain-it’s a medical procedure.

Some patients develop refractory ascites-fluid that won’t go away no matter how many diuretics or paracenteses you do. That’s when TIPS comes in. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt is a procedure where a radiologist creates a tunnel inside your liver, connecting the high-pressure portal vein to a low-pressure vein leading to your heart. It’s like building a bypass. Success rates are 90-95%. But there’s a trade-off: 20-30% of patients develop hepatic encephalopathy-a condition where toxins build up in the brain and cause confusion, forgetfulness, or even coma. It’s not a cure. It’s a tool. And it’s only used when other options fail.

Other Complications: Encephalopathy, Kidney Failure, and Beyond

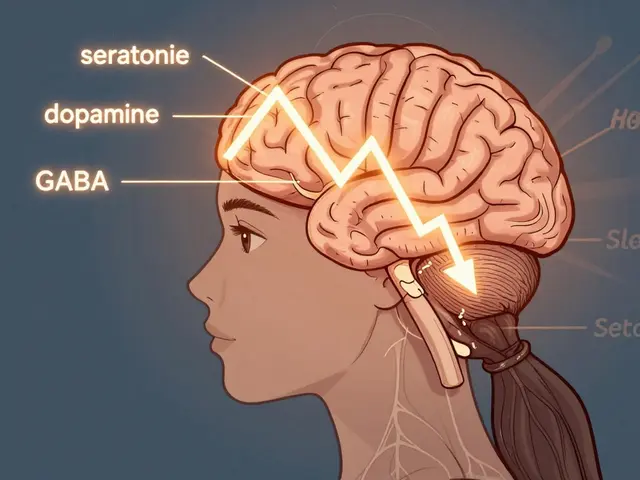

Portal hypertension doesn’t stop at varices and ascites. It sets off a chain reaction. Toxins your liver can’t filter-like ammonia-build up in your blood. That’s hepatic encephalopathy. It affects 30-45% of cirrhotic patients. You might notice mood swings, trouble sleeping, or trouble doing simple math. Some people just seem “off.” It’s often treated with lactulose or rifaximin, but prevention is better: control your diet, avoid sedatives, and treat constipation.Then there’s hepatorenal syndrome. This isn’t kidney disease in the usual sense. It’s your kidneys shutting down because of blood flow changes caused by liver failure. It happens in 18% of hospitalized cirrhotic patients with ascites. Survival without a transplant is grim-often less than three months. The only real solution? Liver transplant.

And let’s not forget the emotional toll. Patients on forums like Reddit and the American Liver Foundation describe constant fear. One nurse had to quit her job because she couldn’t stand for more than 20 minutes. Another said the terror of vomiting blood still haunts him. Studies show people with portal hypertension complications score 35-40 points lower on quality-of-life scales than healthy peers. This isn’t just physical. It’s psychological. It’s social. It’s life-altering.

New Tools and Hope on the Horizon

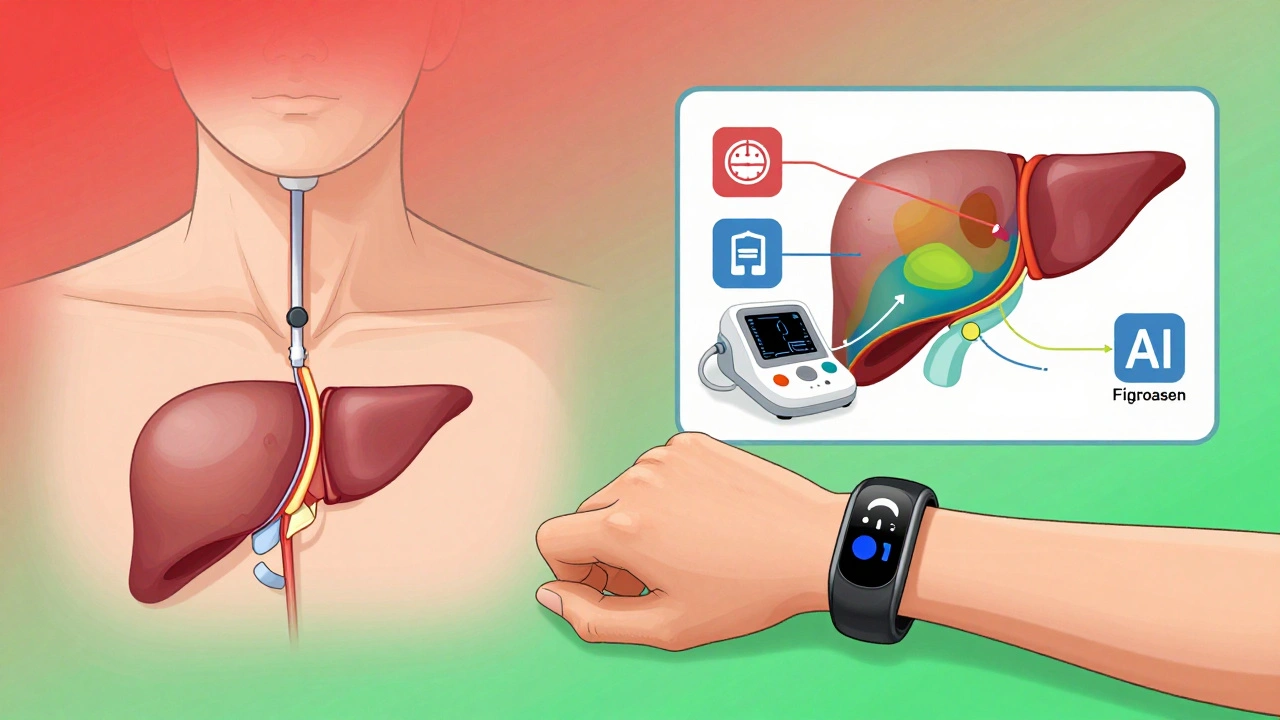

The good news? The field is changing fast. For years, HVPG measurement-the gold standard for checking portal pressure-required a catheter inserted through the neck. It’s invasive. Not every hospital does it. But now, non-invasive tools are getting better. Spleen stiffness measurement using elastography can predict clinically significant portal hypertension with 85% accuracy. FibroScan, already widely used for liver scarring, is now FDA-cleared for portal hypertension assessment.In 2023, the FDA gave breakthrough status to simtuzumab, a drug that targets liver scarring in non-cirrhotic portal hypertension. Early results show a 35% drop in portal pressure. And the Hepatica SmartBand-a wearable device that estimates portal pressure using bioimpedance-just got approved in Europe. It’s not perfect, but it’s a step toward monitoring pressure at home.

AI is also stepping in. Mayo Clinic’s algorithm predicts variceal bleeding with 92% accuracy by analyzing lab results, imaging, and patient history. That means we can now spot who’s at highest risk before they bleed. And there are over a dozen new drugs in phase 2 trials aimed at lowering portal pressure without dropping blood pressure too much-a major hurdle with current beta-blockers.

What You Need to Do Now

If you have cirrhosis or advanced liver disease:- Ask for an HVPG test if you haven’t had one. It’s the only way to know your true risk.

- If you have varices, get band ligation and start a beta-blocker. Don’t pick one-do both.

- For ascites, cut salt. Take your diuretics. Don’t skip albumin after paracentesis.

- Watch for confusion, memory loss, or sleep changes. These could be early signs of encephalopathy.

- Get evaluated for transplant if you have refractory ascites, recurrent bleeding, or kidney issues. The wait in the U.S. is about 14 months. Start now.

Portal hypertension isn’t curable. But it’s manageable. The key isn’t waiting for the next crisis. It’s preventing it before it starts. Every decision you make today-about diet, meds, and follow-ups-directly affects whether you’ll be standing next year, or in the ICU.

What is the normal portal vein pressure?

Normal portal vein pressure ranges from 5 to 10 mmHg. Portal hypertension is diagnosed when pressure exceeds 10 mmHg, or when the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) is greater than 5 mmHg. Clinically significant portal hypertension is defined as HVPG ≥10 mmHg, which is the threshold where complications like varices and ascites begin to appear.

Can portal hypertension be reversed?

Portal hypertension itself cannot be fully reversed once it develops, especially in advanced cirrhosis. However, treating the underlying cause-like stopping alcohol use or controlling hepatitis-can slow or even halt progression. In some cases of early cirrhosis or non-cirrhotic portal hypertension, reducing portal pressure with medications or procedures can improve symptoms and prevent complications. The goal is not cure, but control.

How do beta-blockers help with portal hypertension?

Non-selective beta-blockers like propranolol and nadolol reduce blood flow to the liver by lowering heart rate and cardiac output. This lowers pressure in the portal vein. Studies show they reduce the risk of first variceal bleeding by 45% and rebleeding by up to 50%. The target is a 25% reduction in resting heart rate or a daily dose of 160 mg of propranolol. They’re not for everyone-people with asthma or severe heart failure can’t use them.

What is TIPS, and when is it used?

TIPS stands for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. It’s a procedure where a radiologist creates a tunnel inside the liver to connect the high-pressure portal vein to a low-pressure vein leading to the heart. This bypasses the liver and reduces pressure. TIPS is used when ascites doesn’t respond to diuretics or when varices keep bleeding despite medication and endoscopy. It’s effective but carries a 20-30% risk of causing hepatic encephalopathy, so it’s reserved for selected patients.

Can non-cirrhotic portal hypertension be treated differently?

Yes. Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) often results from portal vein thrombosis, not liver scarring. Treatment focuses on anticoagulation-blood thinners like warfarin or direct oral anticoagulants-to dissolve clots and restore flow. Beta-blockers are generally not used unless varices are present. The cause must be identified first: it could be due to blood disorders, infections, or genetic conditions. Management is tailored to the underlying trigger, not just the pressure.

How often should I be monitored for complications?

If you have cirrhosis, you should be screened for varices with an endoscopy every 2-3 years if no varices are found, or every year if small varices are present. Ascites and liver function should be checked every 3-6 months. If you’ve had a bleed or developed ascites, monitoring increases to every 3 months. Non-invasive tests like FibroScan or spleen stiffness measurements can help reduce the need for frequent endoscopies, but they don’t replace them entirely.

Next Steps and When to Seek Help

If you’re managing portal hypertension, your next move isn’t complicated-it’s consistent. Take your meds. Watch your salt. Keep your appointments. Track your symptoms. If you notice new swelling, confusion, vomiting blood, or sudden weakness, go to the ER. Don’t wait. Don’t call your doctor tomorrow. Go now.For those without cirrhosis but with risk factors-obesity, diabetes, heavy alcohol use-start now. Get your liver checked. A simple ultrasound and blood test can catch early damage. Portal hypertension doesn’t come out of nowhere. It builds slowly. But the window to prevent it is small. Once it hits, the damage is harder to undo.

The future of portal hypertension care is smarter, less invasive, and more personalized. But right now, the tools we have work-if you use them. Your liver can’t speak. But your body can. Listen to it. Act on it. Your life depends on it.

14 Comments

Shubham Pandey

Propranolol works, but who the hell checks their heart rate daily? I just take it and hope for the best.

Elizabeth Farrell

I’ve been managing cirrhosis for 7 years now, and honestly, the biggest game-changer wasn’t the meds-it was learning to cook without salt. No more canned soups, no soy sauce, no processed snacks. It felt impossible at first, but now I actually enjoy the flavor of real food. And my belly? It’s not a water balloon anymore. Small changes, huge difference. You got this.

Sheryl Lynn

How quaint-yet so profoundly inadequate-to reduce portal hypertension to a mere ‘pressure gradient.’ The true pathology lies in the ontological rupture between hepatic architecture and systemic perfusion. Beta-blockers? Merely palliative bandaids on a dying ecosystem. We’re not treating a disease-we’re negotiating with entropy itself. And let’s not forget the spectral haunting of ammonia in the cerebral cortex… the liver’s ghost whispering in the synaptic static.

Paul Santos

Interesting take, but have you considered the role of gut-liver axis dysbiosis in driving NO overproduction? 🤔 Also, TIPS is great, but the encephalopathy risk is basically trading one hell for another. We need better targets than just ‘lower pressure.’ Maybe IL-6 inhibitors? 🤷♂️

Eddy Kimani

Just read this and had to pause. The part about FibroScan being FDA-cleared for portal hypertension? Huge. I’ve been pushing my GI to do non-invasive screening instead of endoscopy every year. The data on spleen stiffness is solid-85% accuracy is better than most labs I’ve seen. If we can replace 80% of endoscopies with elastography, we’re talking massive cost and comfort gains. This is the future.

John Biesecker

Man I just found out my uncle has this and he’s been drinking for 20 years… I told him to stop but he said ‘it’s not that bad’ 😔 I printed out this whole post and left it on his fridge. I hope he reads it. Liver don’t lie. 🫠

Genesis Rubi

They say NAFLD is rising because of Big Soda and fake carbs… but nobody talks about how the government subsidizes corn syrup while starving liver research funding. This is a corporate crime. Wake up America. Your liver is being poisoned by lobbyists.

Doug Hawk

Had TIPS last year. 90% success rate? Yeah, but the encephalopathy hit me hard. Forgot my daughter’s birthday. Couldn’t remember my wife’s name for three days. I didn’t know it could feel like your brain was full of wet cotton. I’m alive, but I’m not the same. The doc said it’s manageable with lactulose… but I still cry at night. No one tells you about the mental toll.

John Morrow

Let’s be real: this entire framework is built on outdated Baveno guidelines from the 2010s. The real breakthrough isn’t in beta-blockers or TIPS-it’s in the emerging class of endothelin receptor antagonists. Phase 2 data shows portal pressure reduction without hypotension. Yet we’re still stuck prescribing propranolol like it’s 2008. The system is ossified. Innovation is being buried under bureaucratic inertia. The data exists. The will doesn’t.

Kristen Yates

I work in a rural clinic. Most of our patients can’t afford spironolactone. Some skip doses because they don’t understand why. We give them pamphlets. But words don’t fill bellies. We need affordable meds, not just guidelines. This post is great-but it’s useless if no one can follow it.

Carolyn Woodard

It’s fascinating how portal hypertension mirrors the human condition-pressure builds, systems fail, and the body seeks escape routes. But the body doesn’t know it’s dying. It just keeps trying. We’re all just vessels trying to carry too much. Maybe medicine isn’t about fixing pressure… but learning to live with it. Quietly. With dignity.

Sandi Allen

THIS IS A GOVERNMENT COVER-UP!! The FDA approves these drugs because they’re owned by Big Pharma!!! The real cure is lemon water and fasting!! Why won’t they tell you?!! They’re silencing the truth!!

John Webber

my dr said i need to cut salt but i love chips… is there a liver friendly chip? 😅

Chelsea Moore

My mom had a bleed last year… I found her on the floor, covered in blood. She didn’t even scream. Just looked at me like she was sorry. I’ve been screaming at doctors ever since. Nobody listens. Nobody cares. I just want someone to say ‘I see you.’