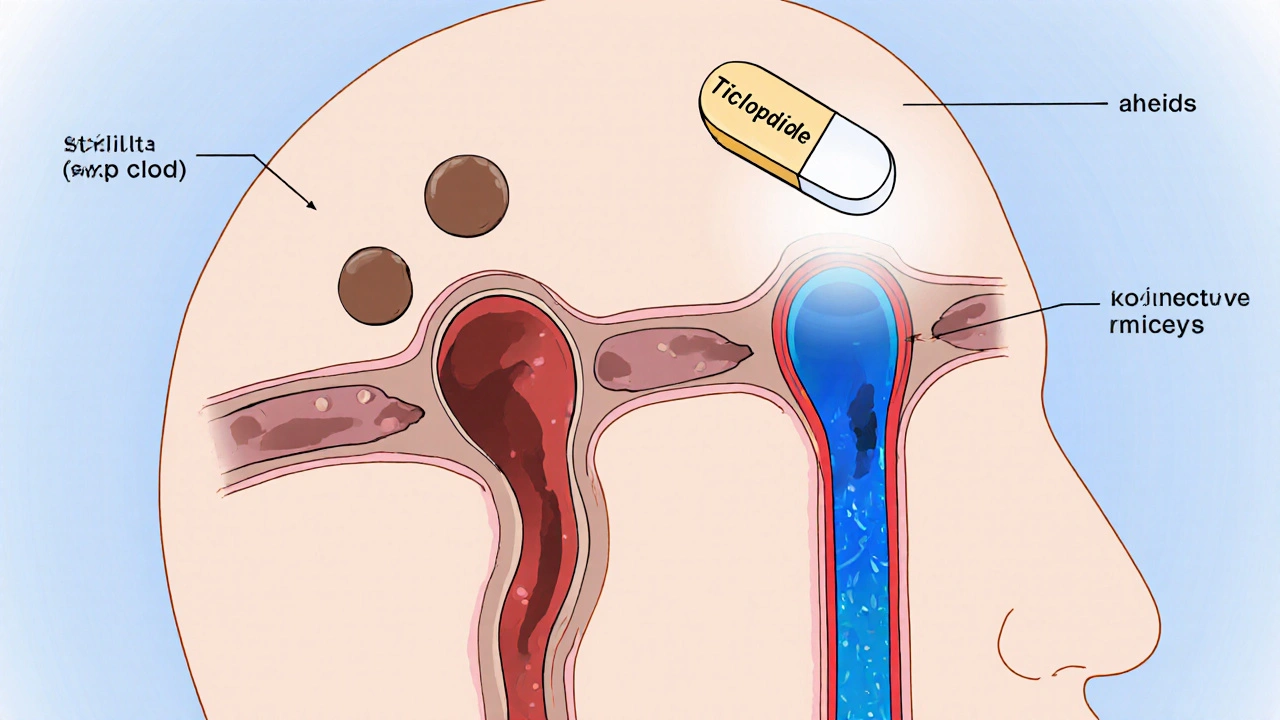

When it comes to preventing stroke, Ticlopidine is an oral antiplatelet medication that blocks the P2Y12 receptor on platelets, reducing their ability to clump together. ticlopidine may not be a household name, but for clinicians managing patients at high risk of clot‑related events, it offers a unique set of advantages.

Why Antiplatelet Therapy Matters in Stroke Prevention

Strokes caused by a blocked artery-known as ischemic strokes-account for roughly 87% of all cases worldwide. The blockage usually starts with a small platelet plug that grows into a larger clot, cutting off blood flow to brain tissue. By interfering with the early stages of clot formation, antiplatelet drugs help keep the vessels open and lower the chance of a serious event.

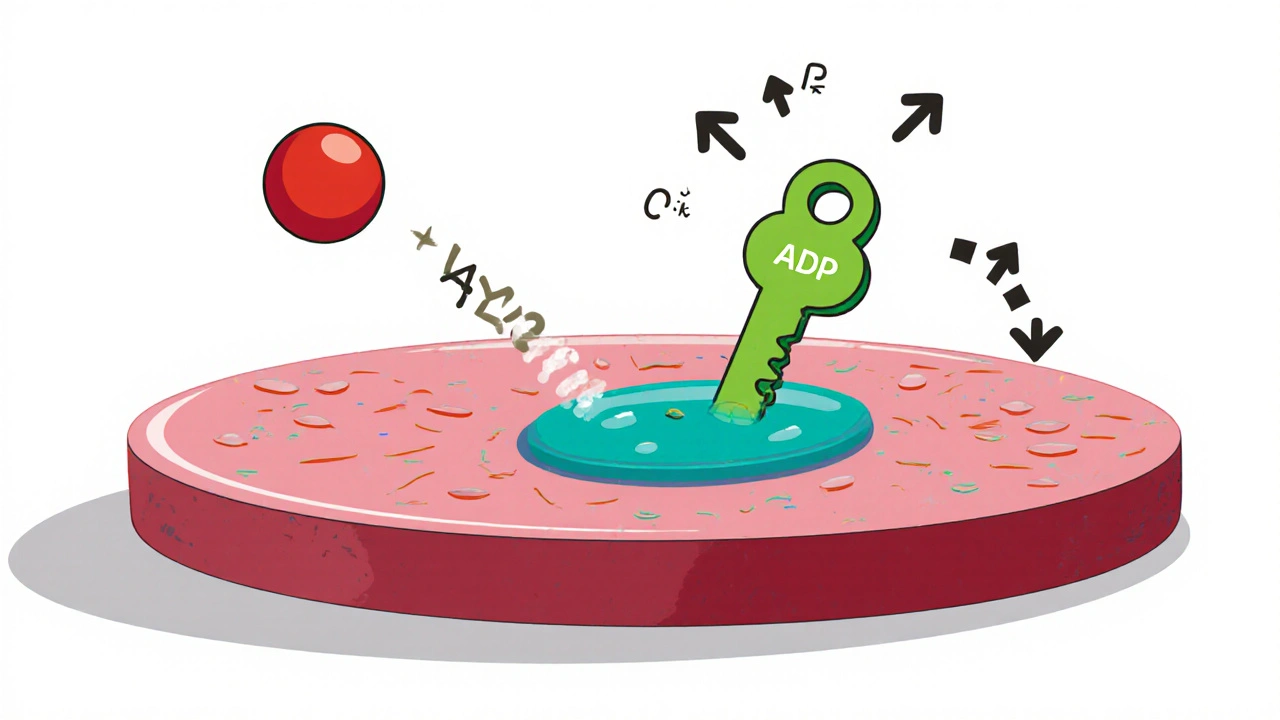

How Ticlopidine Blocks Platelet Aggregation

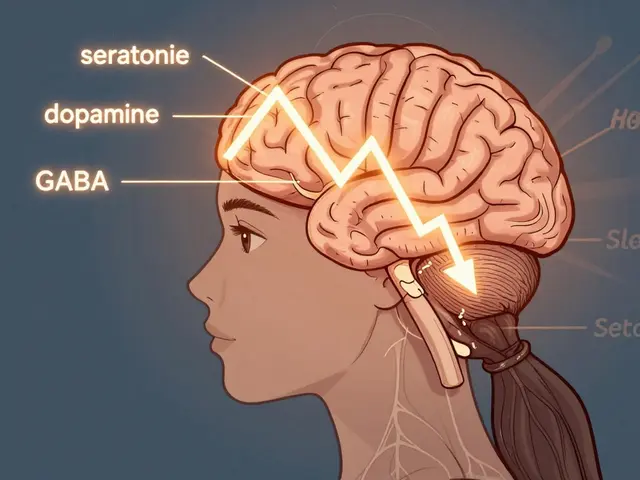

Platelets communicate through the P2Y12 receptor, a protein that responds to ADP (adenosine diphosphate) released during vessel injury. Ticlopidine is metabolised in the liver to an active metabolite that irreversibly binds to this receptor, preventing ADP from activating platelets. This mechanism is similar to newer drugs like clopidogrel, but ticlopidine reaches its peak effect faster because it does not require the same two‑step activation process.

Key Clinical Benefits Over Other Antiplatelets

- Rapid Onset: Therapeutic inhibition appears within 2‑3 days, useful after a recent transient ischemic attack (TIA) when early protection is critical.

- Strong Platelet Inhibition: Studies from the early 2000s showed ticlopidine reduced recurrent stroke rates by about 30% compared with aspirin alone.

- Alternative for Aspirin‑Intolerant Patients: Those who develop gastric irritation or allergic reactions to aspirin can often tolerate ticlopidine.

Comparing Ticlopidine, Clopidogrel, and Aspirin

| Drug | Mechanism | Onset of Action | Typical Dose | Common Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ticlopidine | Irreversible P2Y12 inhibition | 2‑3 days | 250 mg twice daily | Neutropenia, GI upset |

| Clopidogrel | Irreversible P2Y12 inhibition (requires CYP2C19 activation) | 5‑7 days | 75 mg once daily | Bleeding, rash |

| Aspirin | COX‑1 inhibition, reduces thromboxane A2 | 1‑2 days | 75‑325 mg once daily | GI bleeding, ulcers |

Who Stands to Gain the Most from Ticlopidine?

Patients who have already experienced a TIA or a minor ischemic stroke are prime candidates. In particular, those with a history of aspirin intolerance, or those who need a rapid antiplatelet effect while awaiting the full activation of clopidogrel, may benefit. The drug is also useful in regions where newer agents are cost‑prohibitive, offering a budget‑friendly alternative with proven efficacy.

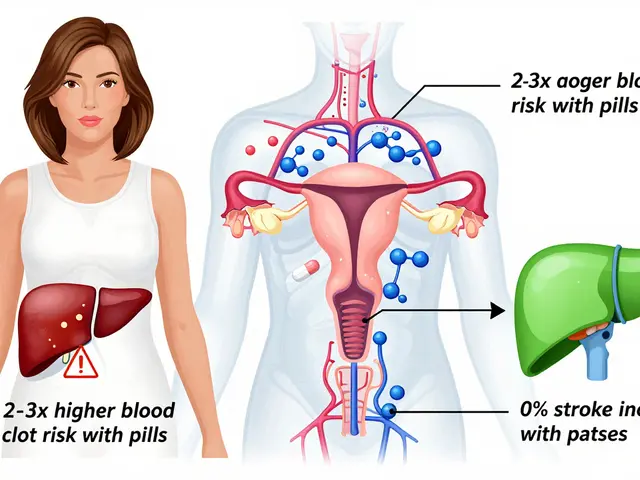

Safety Profile and Monitoring Requirements

While ticlopidine is effective, its safety considerations demand careful monitoring. The most serious risk is neutropenia-a drop in white blood cells that can predispose patients to infection. Because this side effect typically emerges after 2‑4 weeks of therapy, regular complete blood counts (CBC) are recommended during that window. Other common adverse events include gastrointestinal upset, rash, and, rarely, hepatotoxicity.

Patients taking other drugs metabolised by cytochrome P450 enzymes, especially CYP2C19, should be evaluated for potential interactions. For instance, concurrent use of certain antifungals or proton‑pump inhibitors can alter ticlopidine levels, affecting both efficacy and safety.

Practical Tips for Clinicians

- Baseline Labs: Obtain CBC, liver function tests, and assess renal function before starting therapy.

- Monitoring Schedule: Repeat CBC at week 2 and week 4; subsequent checks every 3‑6 months if stable.

- Manage Bleeding Risk: Counsel patients on signs of bleeding and avoid combining with other strong anticoagulants unless absolutely necessary.

- Transition Strategies: When switching from ticlopidine to clopidogrel or vice‑versa, allow a 5‑day washout period to minimise overlapping platelet inhibition.

Current Guidelines and Evidence Base

The American Heart Association (AHA) and European Stroke Organisation (ESO) still list ticlopidine as a Class IIb option for secondary stroke prevention, mainly for patients who cannot tolerate aspirin or clopidogrel. A 2022 meta‑analysis of 11 randomized trials involving over 6,000 patients demonstrated a relative risk reduction of 28% for recurrent ischemic stroke when ticlopidine was added to standard therapy, compared with aspirin alone.

However, newer agents like ticagrelor are gaining favor because they avoid the neutropenia risk and do not require metabolic activation. Still, the cost‑effectiveness of ticlopidine remains compelling in many health systems, particularly in the UK’s NHS formulary where budget constraints are a constant concern.

Bottom Line: When to Choose Ticlopidine

If you’re treating a patient with recent TIA, aspirin allergy, or a need for rapid platelet inhibition, ticlopidine presents a solid, evidence‑backed choice. The key is diligent blood‑count monitoring and patient education about potential side effects. In the right hands, it can markedly lower the chance of a disabling stroke without adding undue risk.

How quickly does ticlopidine start working?

Therapeutic platelet inhibition usually appears within 2‑3 days of starting the standard 250 mg twice‑daily dose.

What are the main side effects to watch for?

The most serious is neutropenia, which can develop after a few weeks. Patients should also be aware of GI upset, rash, and occasional liver enzyme elevations.

Can I take ticlopidine with aspirin?

Combining the two increases bleeding risk and is generally not recommended unless a physician specifically advises it for a short‑term bridge.

Is ticlopidine suitable for patients with kidney disease?

Mild to moderate renal impairment does not require dose adjustment, but severe kidney disease warrants close monitoring and possible dose reduction.

How does ticlopidine compare to newer agents like ticagrelor?

Ticagrelor offers faster onset and no neutropenia risk, but it is more expensive and has a higher bleeding profile. Ticlopidine remains a cost‑effective option when monitoring can be ensured.

12 Comments

Terell Moore

Ah, the grandiose hype around ticlopidine reads like a vintage pharmacology brochure, dripping with self‑importance. The drug’s rapid onset is touted as a miracle, yet the underlying risk of neutropenia is conveniently footnoted. One can almost hear the pretentious chorus chanting about cost‑effectiveness while ignoring the mundane lab work. It’s as if the authors believe that speed trumps safety, a notion I find both naïve and amusing. In short, the allure of quick platelet inhibition is outweighed by the dread of a compromised immune system.

Amber Lintner

I must say, the drama of proclaiming ticlopidine a hero is utterly theatrical. While everyone waves banners for its rapid action, I’m here to whisper that the side‑effects lurk like unseen villains. The romance of a swift platelet block collapses under the spotlight of bone‑marrow suppression. Let’s not ignore the guttural cries of patients who endure weeks of blood‑count anxieties. The narrative feels more like a soap opera than a sober medical discourse.

Lennox Anoff

When one examines the ethical landscape of prescribing ticlopidine, the picture becomes undeniably complex. The drug offers a rapid shield against recurrent strokes, which on the surface appears a noble pursuit. Yet the specter of neutropenia hovers like a moral quandary that cannot be dismissed with a casual glance. Physicians must weigh the urgency of preventing cerebral ischemia against the potential to render a patient immunocompromised. In regions where newer agents are financially out of reach, ticlopidine emerges as a pragmatic compromise, but not without cost. The cost, however, is measured in regular CBCs and the anxiety they provoke. Some argue that this monitoring regimen is a minor inconvenience; others view it as an undue burden on already strained healthcare systems. Moreover, the drug’s interaction profile, especially with CYP2C19 substrates, adds another layer of responsibility. It is incumbent upon the prescriber to conduct a thorough medication reconciliation before initiation. The rapid onset, touted as a virtue, may also precipitate bleeding risks if not carefully managed. One must also consider patient adherence to the twice‑daily dosing schedule, which is less forgiving than a once‑daily regimen. The ethical duty extends to informed consent, ensuring patients comprehend both benefits and hazards. Ultimately, the decision hinges on a delicate balance between immediate protection and long‑term safety. The moral weight of this choice should not be trivialized. As clinicians, we are tasked with navigating these treacherous waters, guided by both evidence and conscience.

Grace Silver

One might pause and consider the deeper implications of a drug that trades speed for vulnerability

It forces us to reflect on how we value immediate outcomes versus sustained health

Max Lilleyman

🔬 Look, ticlopidine isn’t just another pill on the shelf – it’s a bold statement about prioritizing rapid protection. The fact that it reaches therapeutic levels in just a couple of days makes it a contender for acute TIA scenarios. But let’s not sugar‑coat the reality: neutropenia is a serious, sometimes life‑threatening side effect that demands vigilant monitoring. I’ve seen patients with flawless labs turn yellow in weeks because the CBC was missed. The cost‑effectiveness argument holds water only if you have the infrastructure to track blood counts religiously. Otherwise, you’re playing roulette with the immune system. 💊💉

Buddy Bryan

First, the pharmacodynamics of ticlopidine are well‑characterized: irreversible binding to the P2Y12 receptor leads to potent platelet inhibition within 48‑72 hours. Second, the clinical data from early‑2000s trials consistently demonstrate a roughly 30% reduction in recurrent ischemic events compared to aspirin monotherapy. Third, the safety profile, while concerning for neutropenia, can be mitigated via a strict CBC monitoring schedule at weeks 2, 4, and then quarterly if stable. Fourth, drug‑drug interactions, especially with CYP2C19 inhibitors, necessitate a comprehensive medication review prior to initiation. Fifth, patients with mild to moderate renal impairment generally tolerate standard dosing without adjustment, but severe renal disease warrants dose reduction and closer observation. Sixth, dosage adherence is critical; the twice‑daily regimen can be a compliance hurdle compared to once‑daily clopidogrel. Seventh, transitioning between ticlopidine and other antiplatelet agents requires a 5‑day washout to avoid overlapping effects and excess bleeding risk. Eighth, cost considerations remain pivotal in low‑resource settings where newer agents are prohibitive. Finally, the decision to employ ticlopidine should be individualized, balancing rapid anti‑thrombotic needs against the logistical burden of monitoring and potential hematologic toxicity.

Bianca Larasati

Listen up, folks! If you’re staring at a wall of data and feeling stuck, remember that ticlopidine can be a lifesaver when time isn’t on your side. The drug’s rapid kick‑in can slam the brakes on a clot before it does damage, and that’s drama you want in the emergency room. But don’t just chase speed; keep an eye on those blood counts like a hawk. The hero’s journey includes a few gritty checkpoints, but the payoff can be huge for the right patient. Stay motivated, stay vigilant, and you’ll turn those odds in your favor.

Sarah Keller

Remember, the key to making ticlopidine work safely is a team effort – clinicians, nurses, labs, and patients all playing their part. Emphasize the importance of regular CBCs and educate patients on warning signs. With the right support, the rapid antiplatelet effect can be a powerful tool without letting safety slip.

kevin burton

Ticlopidine works by irreversibly blocking the P2Y12 receptor on platelets, which stops them from clumping. It reaches its full effect in about two to three days, faster than clopidogrel. Regular blood‑count checks are essential to catch neutropenia early.

Brett Witcher

The recommended monitoring schedule is as follows: baseline CBC before starting therapy, repeat at week 2 and week 4, and then every 3‑6 months if stable. Any drop in neutrophils below 1.5 × 10⁹/L should prompt immediate reassessment of the treatment plan.

Olivia Harrison

Great summary! It’s helpful to see the balance of rapid action and the need for diligent monitoring laid out clearly. Thanks for making the information accessible.

Abby W

Thanks for the clarity! 😊